In time for Christmas, Archive Assistant Neil Wiffen looks at a nineteenth century list of gifts of beef.

Christmas is almost upon us; the shops are busy and hopefully everyone’s cupboards and fridges have been provisioned ready for the festive day. Mid-winter, the bleakest, darkest and coldest time of the year has, for at least the past two or so millennia, been a time when people come together to feast and celebrate and to look forward to the return of the sun. Today we’re used to shops full of pallets stacked with tubs of chocolates, boxes of beer and so many mince pies and panettones that’d they probably reach the moon placed end-to-end. However, in a pre-industrial age life was lived very much more precariously.

For instance, a ‘fairly’ recent example of dearth occurred at the end of the eighteenth century. A run of poor harvest in the 1790s caused much unrest and consternation through the kingdom This led to the government surveying agriculture across the country as way of finding out what was being grown and what the forthcoming harvests in 1800 and 1801 might yield. Further spells of bad weather in the late 18-teens saw another series of poor harvests. The spectre of famine was only a poor harvest away.

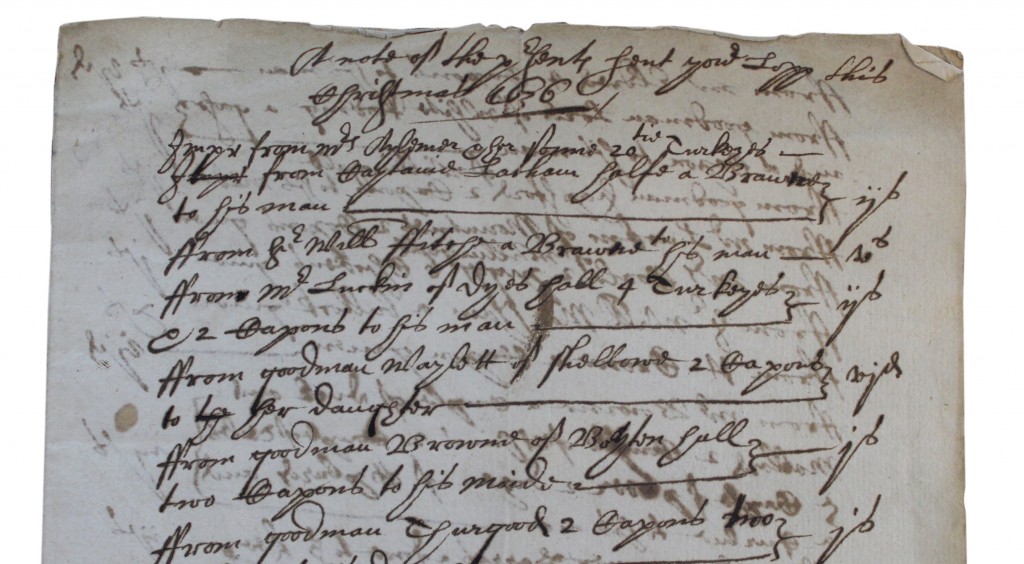

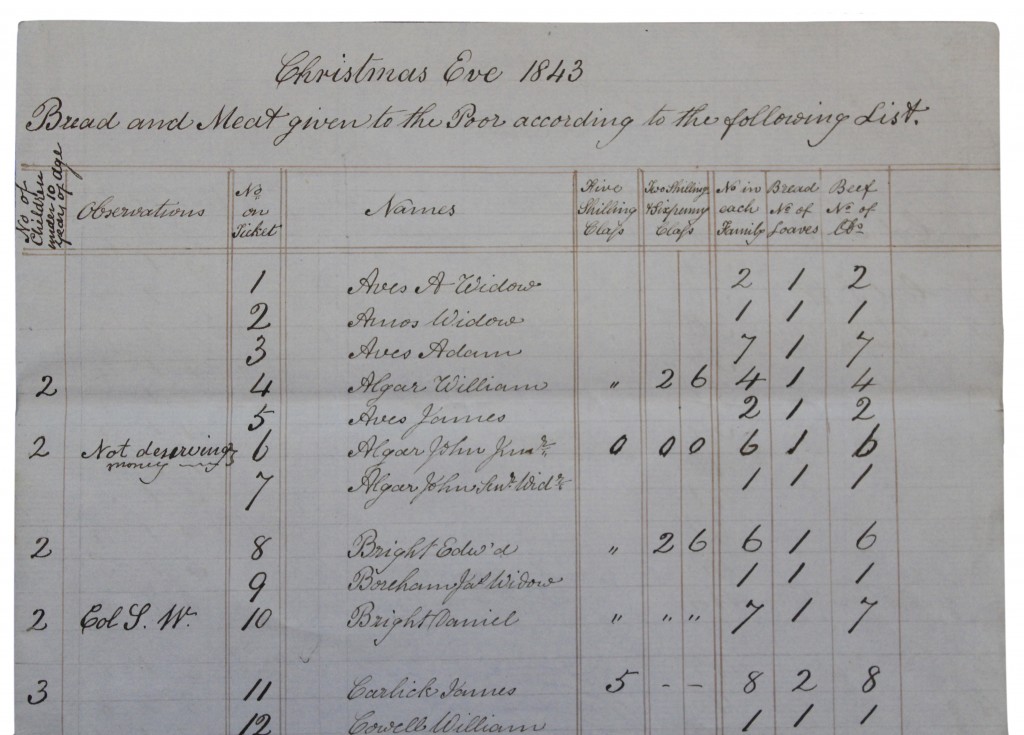

A home-grown and seasonal diet must have become fairly monotonous, and it is to be assumed that all sorts of pickling and preserving must have gone on to eek out and make more interesting, stored food stuffs. Any form of ‘boost’ was surely very welcome and even more so at Christmas. A gift of some form or other to employees was often received at Christmas and in one of the Record Office collections there are lists covering several years, of the distribution of beef to what must be the agricultural labourers and their family members (the Tabor family of Bocking, D/DTa/A33A).

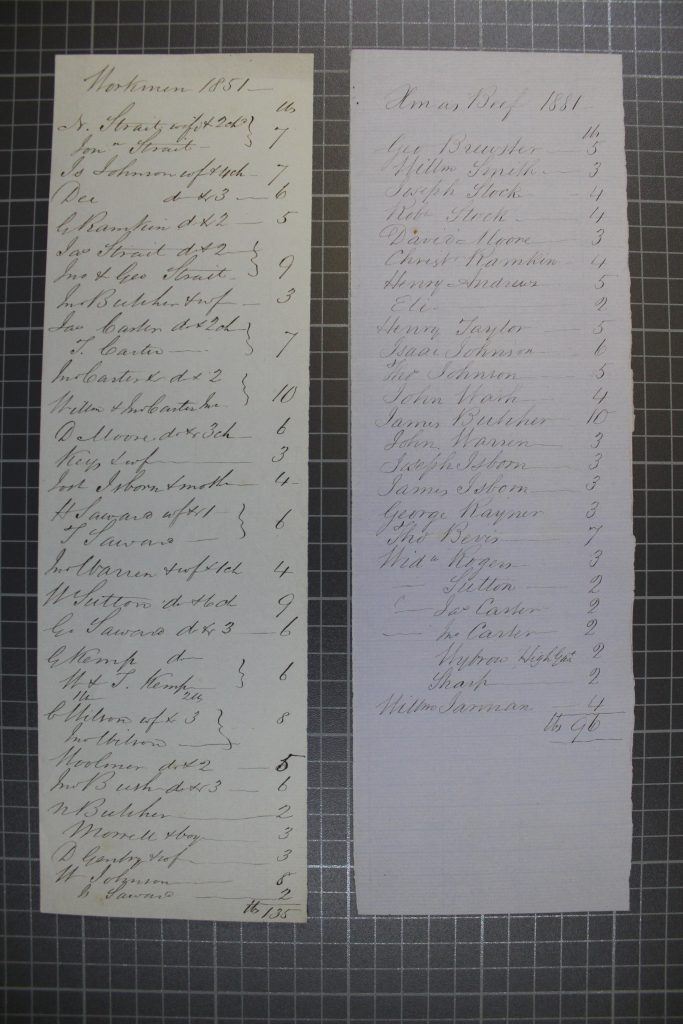

In 1851 there were 24 doles totalling 135lb of beef, while by 1881 the number of distributions had risen to 26 but the total of beef given had fallen to 96lb. In 1851 the first dole or distribution of beef is to ‘N[?]. Strait, wife & 2 ch[ildren], Jon[athan?] Strait, 7lb’. A family group of five, so just over a pound of beef per person. This could be the family of Nathaniel Straight who was recorded as living in Hall(?) Farm Cottages, Bocking, in the 1851 census (TNA, HO 107/1785, p.39). Nathaniel, the head of the household was listed along with his wife Mary and children Jonathan, Henry, Ann and Elizabeth. They were all locals, each listing Bocking as their place of birth and all, except the girls who worked in the local silk trade, were agricultural labourers.

The entry from the list gives a household of five, but the census shows six. The census was taken in the spring and this list is from the end of the year. Had one of the children left home? If Jonathan was still at home, as suggested above, could it have been Henry, who at 18, might have moved on?

We can perhaps assume that those listed were all employees on the Tabor farms. However, the list from 1881 suggests that this might not have always been the case for a ‘Wid[do]w Rogers is listed having received 3lb of beef. Was she the relict of a now dead employee receiving some form of alms? Does this show compassion on behalf of the Tabor family?

I have just scratched the surface with just these two lists. How much more can be discovered about the lives of those listed – what connections might be uncovered? So, if you’re looking for a project for the New Year, what better than to take up this task. Do you fancy uncovering some ‘lost’ lives? If so, do get in contact for a chat. Also, there are some other documents if you search Essex Archives Online for ‘Christmas’ and ‘beef’, and I’m sure there are many other examples of gifts of food and drink waiting to be found. How about an expanded piece of research for this time next year? You know it makes sense.

For the time being, let us leave the recipients of the Christmas beef in Bocking (and we can only imagine how much they enjoyed their Christmas beef) and look forward to the next few days. Have you decided upon a large fowl, a chicken, duck or goose, a shoulder of lamb or bit o’ mutton, pork, gammon or ham, a plant-based nutty alternative, perhaps a ‘turkey’ made out of tofu (yes, they do exist!), or a meal of roasted root vegetables, sprouts and onion gravy? Whatever it is that you sit down to on December 25th, with family, friends and loved ones, we wish you all a very Happy Christmas and peaceful New Year and look forward to welcoming you to the Record Office in 2023 – maybe even to start research on these lists from Bocking!