While the Essex Record Office might be closed to physical researchers it is still open for remote users via our Essex Archives Online (EAO) service that contains over three-quarters of a million digital images of parish registers, wills and some other records. This service has been up and running since 2011 and in that time researchers from across the globe have made use of the service. And it is a dynamic service as new images are added as and when relevant documents have been deposited and digitized.

In this Blog post EAO user Ian Beckwith has kindly shared some of his research that he has undertaken whilst using our parish register digital images. Ian is a seasoned user of the service and has been using it for several years but if you are new to research and are thinking of possibly taking out a subscription then it is worth considering the wonderful breadth of what is available. So, to begin with Archive Assistant Neil Wiffen discusses how to get started.

During the 20 years that I have worked at ERO I have been advising researchers on how to start making use of the digital images that are on EAO and here are some of my tips.

Firstly, I would strongly recommend that before you take out a subscription you familiarize yourself with the EAO catalogue. It is completely free to search the catalogue as much as you wish. There are several ‘User Guides’ which are located at the bottom of the home page (https://www.essexarchivesonline.co.uk/) so scroll down and have a read of these.

Secondly, have a go at searching the catalogue by trying out a simple search – try typing in the wide white text box (which contains ‘search the archive’) the name of the parish you are interested in and ‘church register’ and click ‘Search’. This will bring up instances of all sorts of registers, not just church, or parish, registers, for a certain place. Some of these won’t have digitized images associated with them so this is why it is essential to check that what you want to look at has digital images before taking out a subscription. It will, however, give you an idea of the range of documents that the ERO looks after. All the Church of England parish registers deposited in the ERO, except for a few of the most recent ones, have been digitized, so you should find that they all have the a picture frame icon at the end of their entry in the search results.

By clicking on the ‘Reference’ or ‘Description’ you will be taken to the full catalogue entry for a document which might well give you further information. You might find that it isn’t really what you’re looking for. But if it is, remember to check for the photo frame icon to find out whether there is a digital image associated with the document .

A quick way to search for parish registers in particular is to look at the ‘Parish Register’ section of EAO (top right-hand corner). Here you will be able to refine your search to the parish you are interested in. If what you are looking for isn’t there (or if it is there but doesn’t have ‘Digital images’ next to it) then don’t take out a subscription. It is worth remembering that not every parish will have records going back to 1538 so do check the catalogue before subscribing to avoid disappointment.

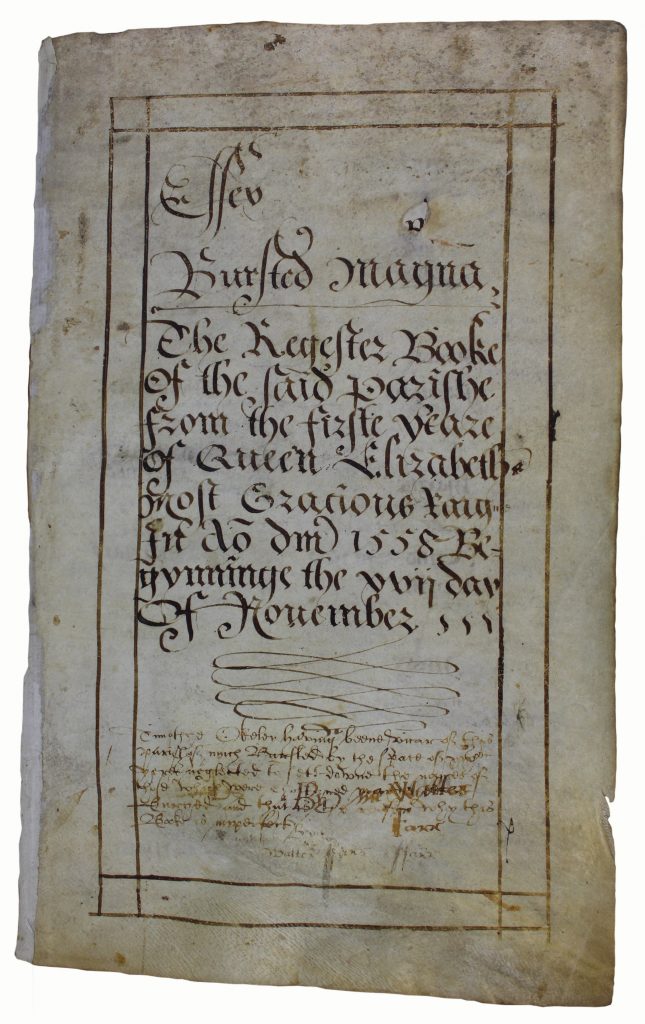

Every parish has its own unique number assigned to it. Great Burstead, for example, is D/P 139 and registers of baptisms, marriages and burials come under D/P 139/1. The first register, which covers 1559 to 1654, is then catalogued as D/P 139/1/0. Take time to familiarize yourself with the catalogue before taking out a subscription.

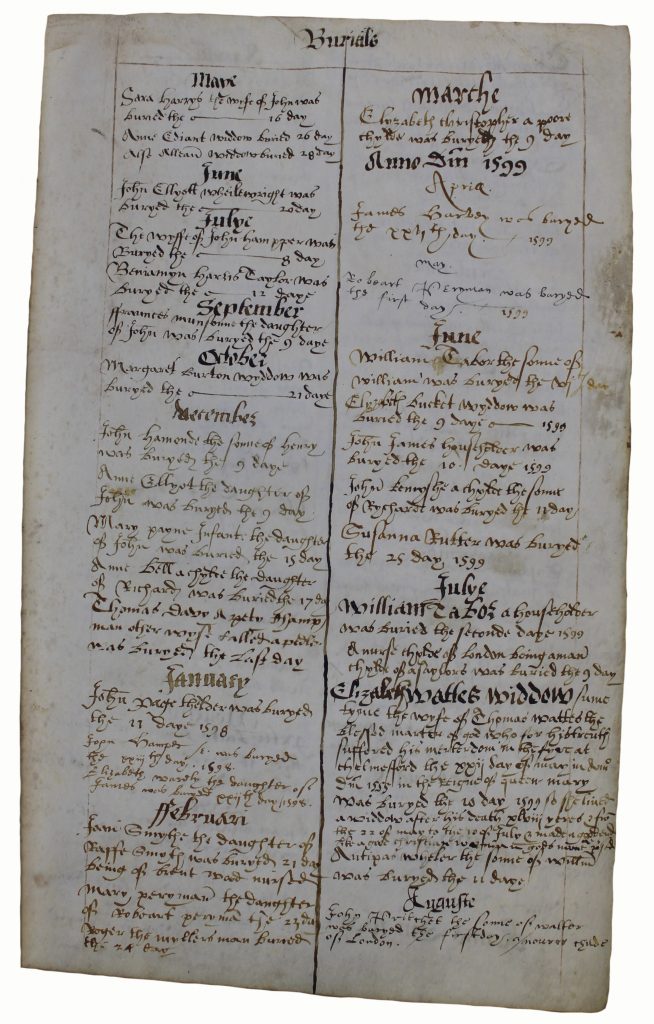

And do bear in mind that even if a parish register survives then early registers have baptisms, marriages and burial scattered throughout them so you will probably need to go hunting through the register for the entry that might be there – or might not . In the Tudor, Stuart and Georgian period it was very much down to the individual incumbent, or his deputy, as to how much effort was put into keeping the registers up to date. Not every vicar, rector or church clerk was as assiduous a record keeper as we might have liked him to have been. Fortunately, if you have a subscription to Ancestry, we have worked together with them to create a name index, which can take a lot of the leg work out your research. You can even buy digital images of what you find directly from Ancestry.

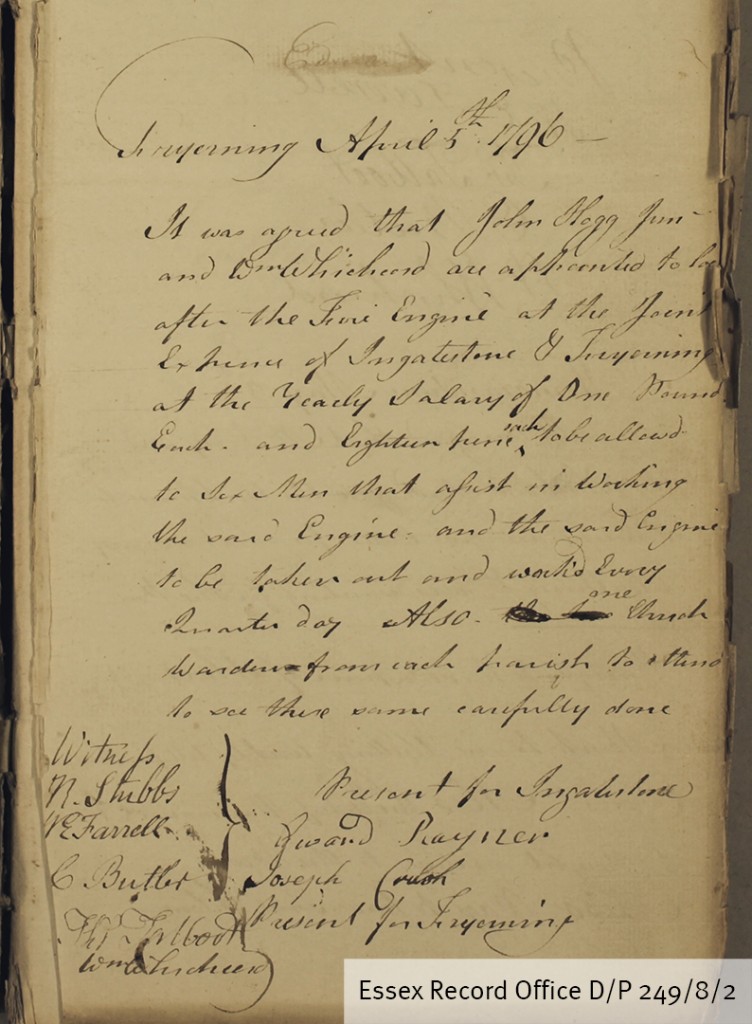

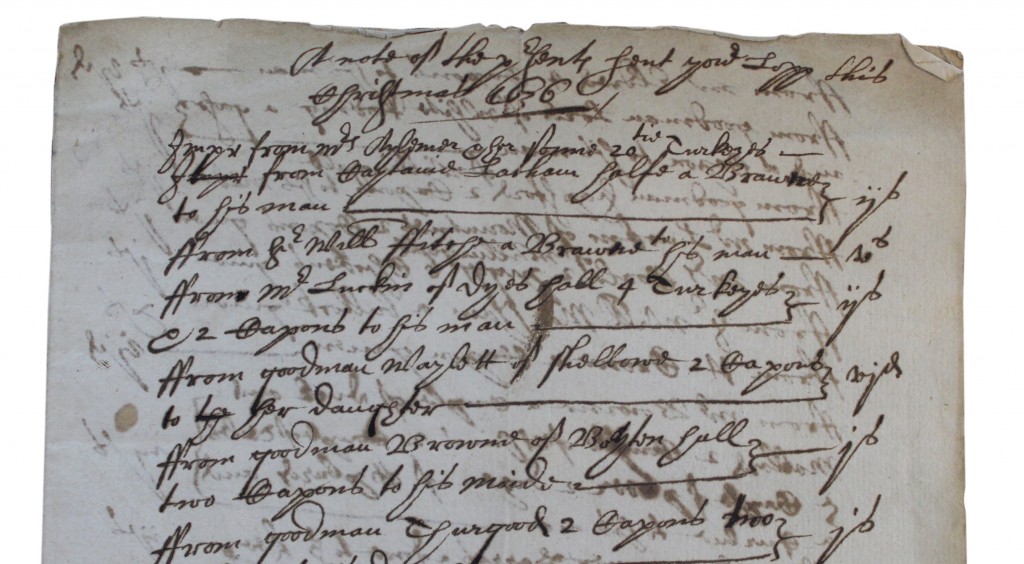

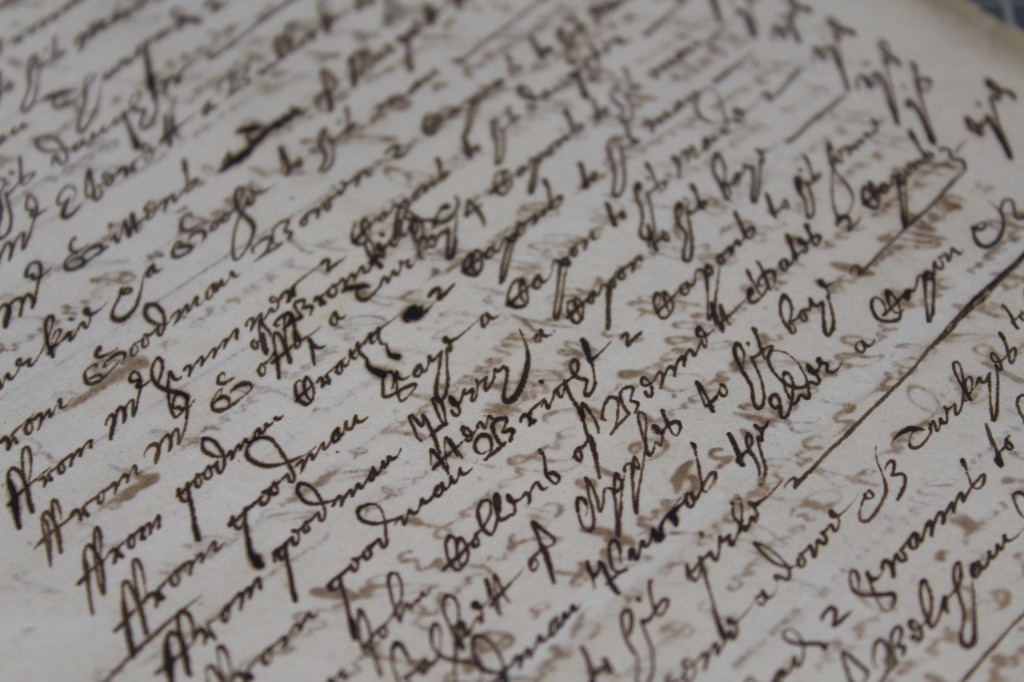

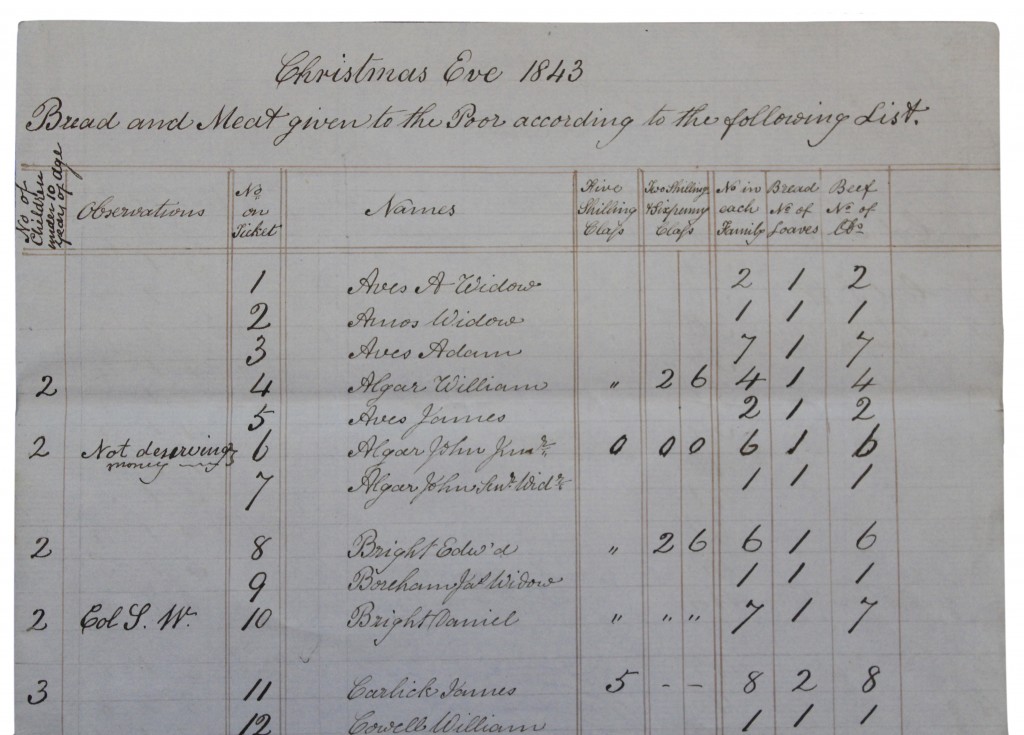

Handwriting can also be difficult to read, although some incumbents like Rev Thomas Cox in Broomfield and the famous Essex historian Rev Philip Morant, have beautifully clear handwriting. Sometimes the writing is faint or illegible and the register itself might be damaged. Remember these were working documents that have spent several centuries in damp and cold churches before being deposited at ERO.

One last thing, if you have identified that there are parish registers that you want to look though that have digital images associated with them, and you take out a subscription, then make sure that you take down the reference of what you have looked at and what you have found as you work your way through them. This will save time in the long-term and if you share your research with others you can tell others in what document you found the information.

I hope I haven’t put you off after all that but I do have one last warning: historical research can be addictive. You might start out looking for one thing but get distracted by something else. After 20 years of working at ERO I know there’s always another new topic of interest just lurking over the page!

Neil Wiffen – Archive Assistant.

If you require any assistance, having taken out a subscription, then you can contact the Duty Archivist at ero.enquiry@essex.gov.uk. While the Record Office is shut, emails are being monitored remotely during the present crisis. Please bear with us though.

Parish Registers – Researching Remotely

I, like many others of my age and with underlying health conditions, am in self-isolation. But this doesn’t mean that I can’t get on with research. Thanks to the digital age there’s so much available on-line for the local historian to work on, e.g. Essex parish registers, which, thanks to the wonders of the ERO, are at my finger-tips on my laptop. There’s a subscription to pay, but once you’re registered., you can log-in, click on ‘Parish Registers’ in the top bar, scroll down the page until you find ‘Choose a letter’, then ‘Choose a parish’ and finally ‘Choose a church’. Up will come a table, telling you when your chosen registers begin, click on ‘View’ in the right hand column, and the register will appear. You need to know that in the case of the earliest registers, the baptism, marriage and burial entries were written up in one book, sometimes in different sections of the book, sometimes together as they occurred through the year. Later registers record baptisms, marriages and burials in dedicated volumes. When the image of your selected register appears, click on the rubric ‘To enhance this image… ’ and the image will expand to fill the screen. Away you go!

In September 1538, King Henry VIII’s Vicar General, Thomas Cromwell, issued an injunction to every parish priest in England requiring him to keep a record of all baptisms, marriages, and burials in his parish. In Essex at least seventy-five parishes have registers beginning in about 1538. Most of these survivals are copies made in the reign of Elizabeth I, either by the incumbent or the parish clerk, from the old book, which was then apparently discarded.[i] Many other registers begin in the reign of Elizabeth I. Apart from the marriages, baptisms and burials that are the building blocks of family reconstitution, what else can we learn from scrutinising parish registers?

In rural Essex as elsewhere in the sixteenth century it was taken as a given that God existed. No one’s head was bothered by whether the earth was the centre of the universe (it obviously was) or whether God was in his heaven up above while hell was down below (they undoubtedly were).[ii] The only issue was whether God was Protestant or Catholic. The wrong choice could cost you your life in this world and your salvation in the next. When it came to making this choice, parishioners in England had been on something of a roller-coaster ride since 1538. Four years before Cromwell issued his injunction introducing parish registers the Pope’s authority over the English Church had been abolished and the King had made himself Supreme Head of the Church in England. Between 1536 and 1541 the Dissolution of the Monasteries had seen the closure of over 900 monastic foundations, the dispersal of the monks and nuns who occupied them, and the sale of their vast landed estates. Yet the parish registers that survive from this period show that, while these upheavals were taking place, baptisms, marriages and burials carried on as normal. The services of the Church continued to be said in Latin, in the form in which they had been since time immemorial. It was not until 1549, two years after the death of Henry VIII, that the mass was first said in English. Four years later the Protestant Edward VI was succeeded by his half-sister the Catholic Mary Tudor, Henry’s daughter by Catherine of Aragon, and during the next five years England returned to obedience to Rome, the services in the parish churches reverted to Latin, the traditional rites and ceremonies were restored, and images and treasures that had been hidden were brought out again, only for all this to be reversed in 1558 when Elizabeth I came to the throne: again the Pope’s authority over the English Church was abolished and the Queen was proclaimed Supreme Governor of the Church.[iii] On May 8th 1559 the Act of Uniformity, authorising the use of the new Book of Common Prayer, received the Royal approval. The new prayer book, which replaced all other service books, came into use on 24th June 1559.

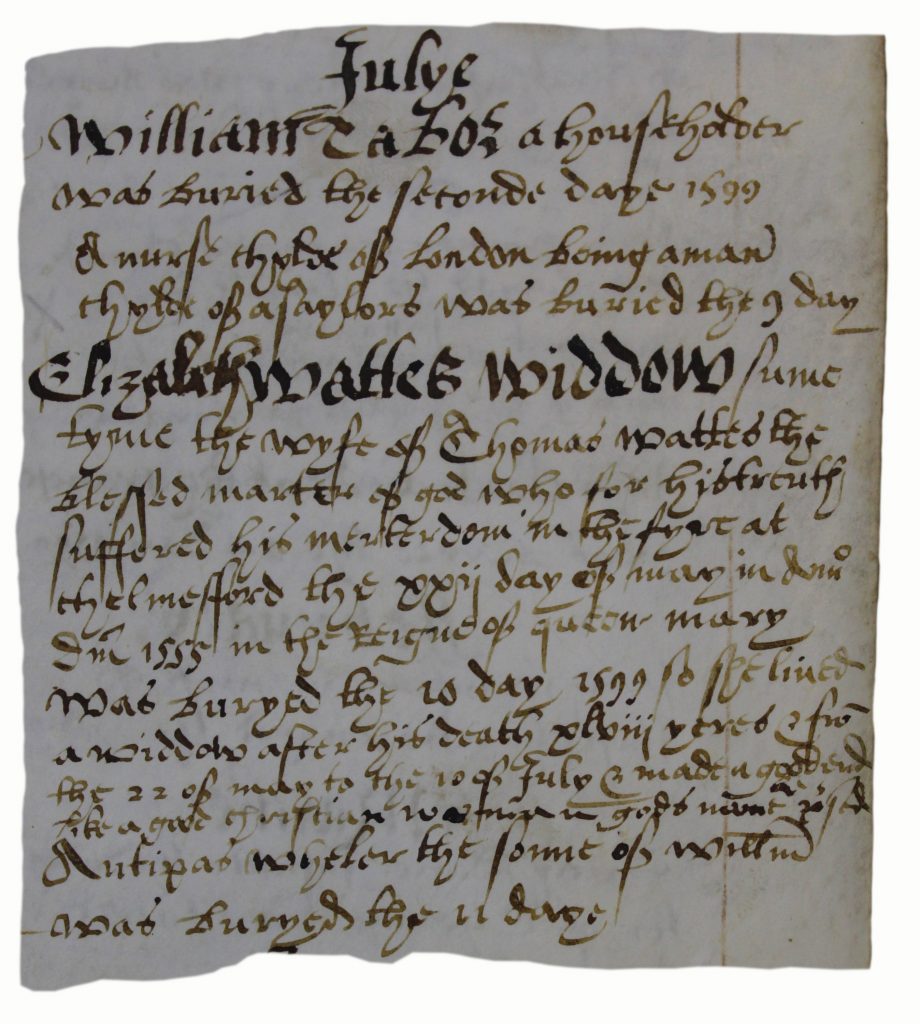

Occasionally, however, in the midst of the routine recording of rites of passage, the registers provide glimpses of the impact of these changes at parish level. In July 1599 the Great Burstead register recorded that

Elizabeth Wattes Widdow sume tyme the wife of Thomas Wattes the blessed

marter of god who for his treuth suffered his merterdom in the fyre at

Chelmesford the xxij day of may in A[nn]o D[o]m[ini] 1555 in the Reigne of

queen mary was buryed the 10 day 1599 so she liued a widow after his death

xlviij yeres & fro[m] the 22 of may to the 10 july & made a good end like a

good Christian woman in gods name.[iv]

Thomas Watts was one of almost eighty Essex men and women who were burned at the stake in the reign of Mary Tudor for refusing to recant their Protestant beliefs.[v] A full account of Thomas Watts’ martyrdom is provided in John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, more correctly titled Acts and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, first published in 1563 and greatly expanded in 1570.[vi] Described as a linen draper of Billericay, then part of the parish of Great Burstead, Thomas Watts had, according to Foxe ‘daily expected to be taken by God’s adversaries’. Accordingly he had assigned his property to his wife and children and donated his stock of cloth to the poor. He was arrested on April 26th 1555 and brought before Lord Rich at Chelmsford, accused of not attending church, i.e. hearing mass. Interrogated by Sir Anthony Browne, who, with Rich, had been appointed to purge Essex of heretics, as to why he had embraced his heretical views, Watts replied that

You taught me and no one more than you. For, in King Edward’s days

in open sessions you said the mass was abominable trumpery, earnestly

exhorting that none should believe therein, but that our belief should be

only in Christ.[vii]

It seems that Watts had also spoken treasonable words against the Queen’s husband, King Philip.[viii] Unable to persuade Thomas Watts to recant, he was sent to Bishop Bonner, ‘the bloody bishop, …’.[ix] Essex was then within the diocese of London and Edmund Bonner was its bishop, first under Henry VIII and again under Mary. He remained staunchly Catholic during the reigns of Edward VI and Elizabeth. Although usually depicted as sadistic and merciless, it is worth noting that even Foxe acknowledges that Bonner made several attempts to persuade Watts (and others) to recant, ‘gave him several hearings, and, as usual, many arguments with much entreaty, … but his preaching availed not, and he resorted to his last revenge – that of condemnation’. ‘I am weary to live in such idolatry as you would have me live in’, Watts is alleged to have said, and signed the confession of heresy. Faced by his refusal, Bishop Bonner had little choice but to consign Thomas Watts to the secular arm, the Church not being allowed to take life, to suffer the penalty prescribed by the Statute De Heretico Comburando (Concerning the Burning of Heretics) of 1401, originally intended to deal with Lollards.[x]

Returned from the Bishop of London’s prison to Chelmsford, Thomas Watts was lodged at ‘Mr Scott’s, an inn in Chelmsford where were Mr Haukes and the rest that came down to their burning, who all prayed together’. Watts then withdrew to pray by himself, after which he met his wife and children for the last time, exhorting them to have no regrets but to glory in the sacrifice he was making for the sake of Jesus. So powerful were his words that, it is said, two of his children offered to go to the stake with him. At the stake, after he had kissed it, he called out to Lord Rich, who was supervising the execution: “beware, for you do against your own conscience herein, and without you repent, the Lord will revenge it”. ‘Thus did this good martyr offer his body to the fire, in defence of the true gospel of the Saviour’.[xi]

It seems unlikely that Rich, a man whose name is a byword for cruelty, sadism, dishonesty, ruthlessness and treachery, possessed a conscience. Born about 1496, Richard Rich was a lawyer who entered the service of Thomas 1st Baron Audley of Walden,, who assisted Rich to become MP for Colchester.[xii] In 1533 Rich was knighted and became Solicitor General. In this capacity, he used selective quotations from a private conversation with Thomas More in the Tower in evidence at More’s trial. In 1536 he was appointed Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations, charged with the disposal of former monastic estates, a position that he used to enrich himself. In 1546 he personally tortured the Lincolnshire Protestant martyr, Ann Askew, in the Tower. During the reign of Edward VI, as Lord Chancellor, however, he presented himself as a reformer, taking part in the trials of Bishops Gardiner and Bonner. Yet in Mary’s reign he helped restore the old religion, actively persecuting those like Thomas Watts of Billericay who refused to conform. Under Elizabeth he sat on a Commission to enquire into grants made during the previous reign and was called upon to advise on the Queen’s marriage. Richard Rich died on 11th of June 1558 at Rochford and was buried at Felsted on the 8th of July. The entry in the Felsted register gives only the bare facts. For those at Felstead who had dealings with him, Richard Rich, first baron Rich, must have been terrifying.[xiii]

In Elizabeth’s reign, others submitted to the Religious Settlement but made their resistance covertly, like the parson of Great Baddow who recorded the burial of Joan Smythe on May 1st 1572 ‘being the purificacion even of o[ur] lady St Mary’ (i.e. the evening preceding the feastday).

Ian Beckwith

[i] It is not necessarily clear by whom the registers were kept. Although the entries for the preceding week were supposed to be read to the congregation at the principal service on Sunday, there are indications that some were written up at the year’s end (24th March), possibly from notes on slips of paper. The penmanship of the entries remains generally of a very high standard until the last decade of the sixteenth century, when it often becomes slapdash and much less legible.

[ii] The realisation that the world was not flat, as the circumnavigation of the globe by Magellan and Drake demonstrated, did not shake the belief in this three-decker image of the universe.

[iii] The change from Supreme Head as Henry VIII was designated, to Supreme Governor, it has been claimed, reflects the opinion that a woman could not be ‘Head’ of the Church. However, when Elizabeth was succeeded by James VI of Scotland, the title ‘Governor’ was retained and continued to be used by every subsequent monarch, male and female.

[iv] ERO, D/P 139/1/0, Image 49. However, the length of her widowhood seems to have been miscalculated.

[v] J E Oxley, The Reformation in Essex to the Death of Mary, Manchester University Press, 1965, pp.210-237. Coincidentally, my copy was withdrawn from Billericay Public Library in about 2013.

[vi] I have drawn upon an edition of 1860, published in Philadelphia. The account of Thomas Watts’ martyrdom is on p.367. The Book of Martyrs has been blamed for inciting anti-Catholic sentiment in England.

[vii] Foxe, p.367

[viii] Mary had married Philip on 25th July 1554

[ix] Foxe, p.367

[x] Several Essex Lollards were burned at the stake in Henry VIII’s reign. The purpose of burning was to act not just as a deterrent but also as a purgative, to rid the realm of disease. See David Nicholls, The Theatre of Martyrdom in the French Reformation, Past & Present, Vol 121, Issue 1, November 1988, pp 49-73.

[xi] Foxe p.367.

[xii] Thomas Audley (1488-1544), formerly MP for Colchester, a member of Cardinal Wolsey’s household, Speaker of the Commons during the Reformation Parliament and Lord Chancellor of England from 1533-1544

[xiii] Born about 1496, Richard Rich was a lawyer who entered the service of Thomas Audley, who assisted him to become MP for Colchester. In 1533 Rich was knighted and became Solicitor General. In this capacity, he used selective quotations from a private conversation with Thomas More in the Tower in evidence at More’s trial. In 1536 he was appointed Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations, charged with the disposal of former monastic estates, a position that he used to enrich himself. In 1546 he personally tortured the Lincolnshire Protestant martyr, Ann Askew, in the Tower. During the reign of Edward VI, as Lord Chancellor, however, he appeared as a reformer, taking part in the trials of Bishops Gardiner and Bonner, yet in Mary’s reign he helped restore the old religion, actively persecuting those who refused to conform. Under Elizabeth he sat on a Commission to enquire into grants made during the previous reign and was called upon to advise on the Queen’s marriage.