As episode 17 of series 5 of Great British Railway Journeys airs on BBC2 and Michael Portillo takes in some of the sights of our great county, we thought we would share some items from our collection to accompany his experience of oyster dredging on Mersea Island, and his visits to a model farm at Tiptree and to the world’s first purpose-built radio factory, Marconi’s in Chelmsford.

Oyster dredging on Mersea Island

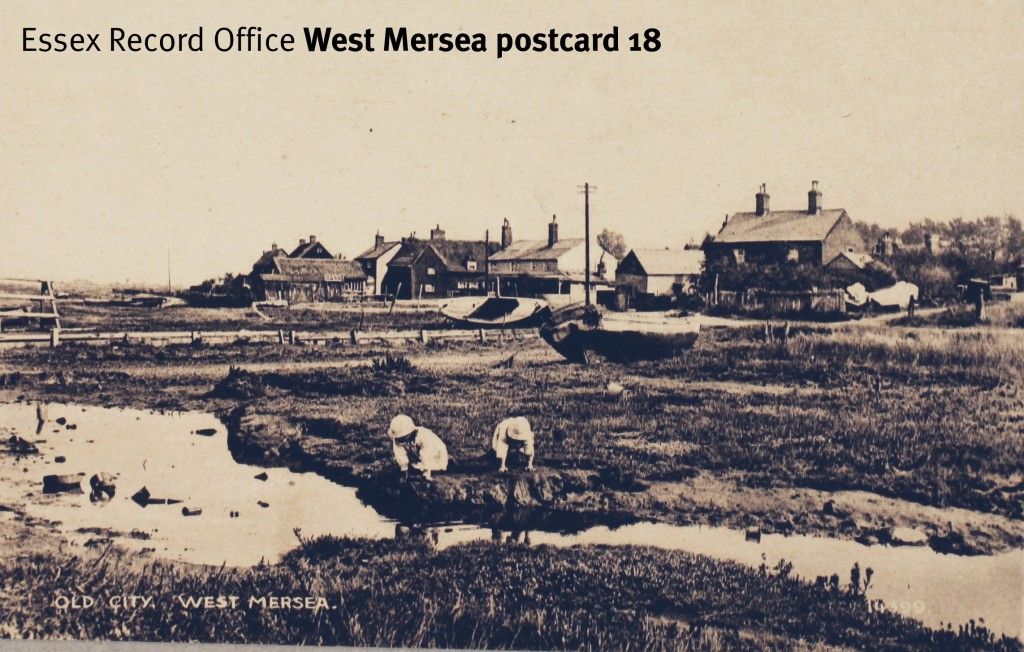

Mersea Island lies 9 miles south-east of Colchester, in the estuary of the Blackwater and Colne rivers. It is joined to the mainland by a causeway, and there is evidence of human habitation stretching back to pre-Roman times. Oysters have been gathered and consumed on Mersea for centuries, with oyster shells being found next to the remains of Celtic salt workings. The gathering of uncultured oysters gradually gave way to cultivation, and Mersea oysters were exported by the barrel load to Billingsgate Fish Market in London, and further afield to the continent.

Competition amongst oyster gatherers in Essex has sometimes led to outbreaks of violence; during the reign of Edward III for example, a disagreement between men from Brightlingsea, Alresford, Wivenhoe, Fingringhoe, Mease, Salcott and Tollesbury over fishing rights resulted in the drowning of three men.

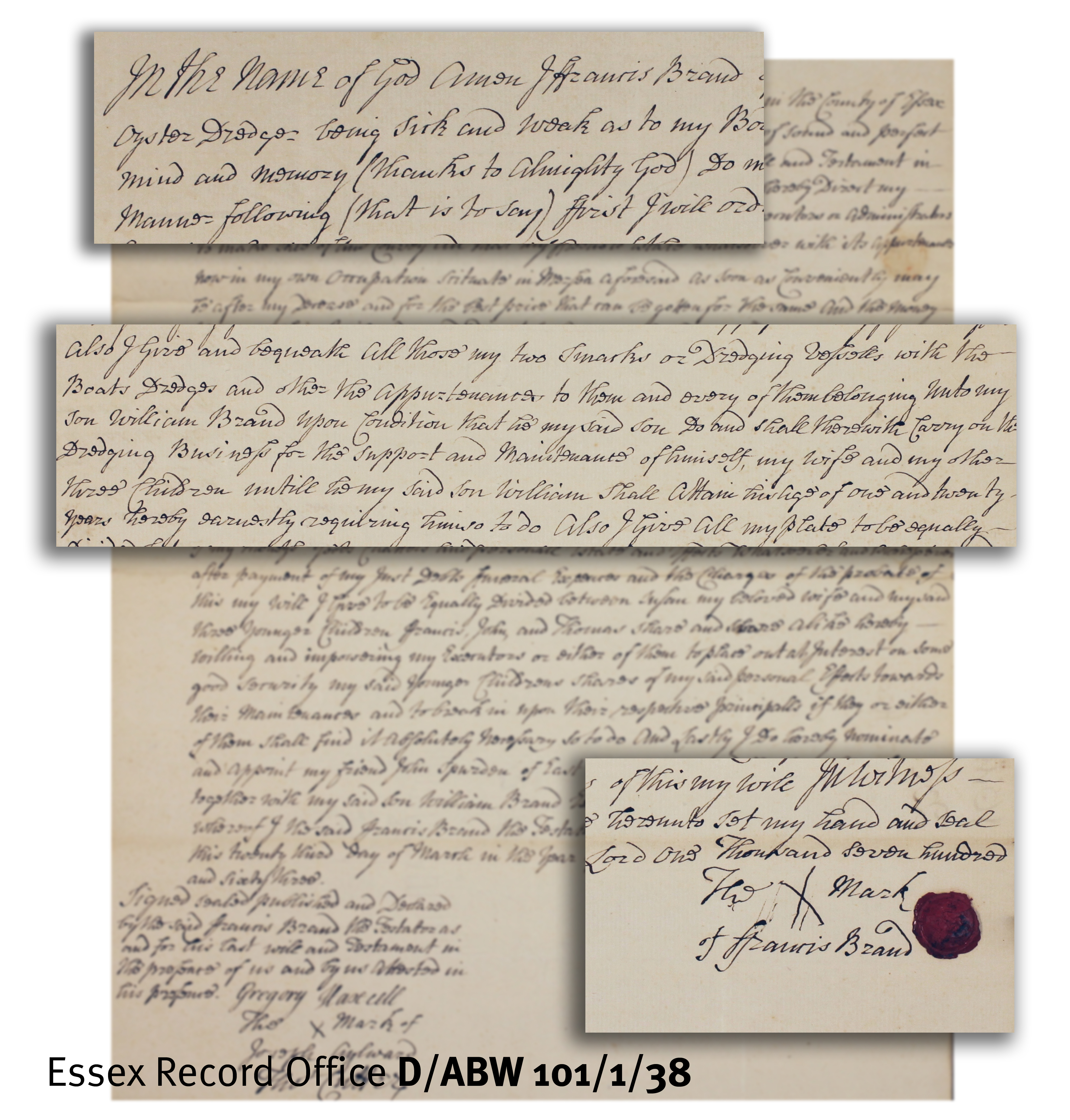

Mersea’s history of oyster fishing is evident in records held in our collection. Our will collection shows how prevalent the oyster trade was amongst Mersea inhabitants, such as this one of Frances Brand, an oyster dredger of West Mersea, dated 1763 (D/ABW 101/1/38). The will includes arrangements for Brand’s two oyster smacks: ‘I give and bequeath all those my two smacks or dredging vessles with the boats dredges and other the appurtances to them and every of them belonging unto my son William Brand upon condition that he my said son … shall therewith carry on the dredging business for the support and maintenance of himself, my wife and my other three children untill he my said son William shall attain … one and twenty years hereby earnestly requiring him so to do.’

Mersea Museum’s website has several great historic photographs of the Mersea oyster trade, such as this one, of members of the Tollesbury and Mersea Oyster Company men outside the Packing Shed circa 1908.

Model farm at Tiptree

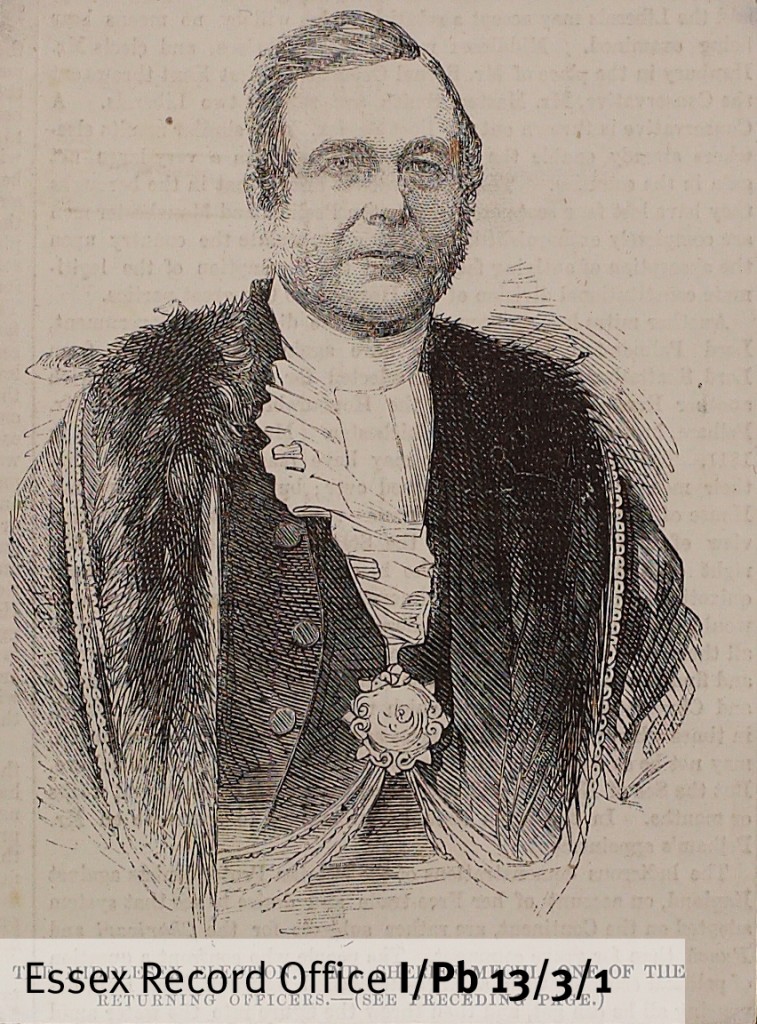

Before broadcast, we are making an educated guess that the ‘model farming establishment in Tiptree’ is the farm set up by John Joseph Mechi (1802-1880) in the 1840s. Mechi, having made a fortune as a razor-strop manufacturer, decided to turn his attention to farming and apply his talents to the improvement of agriculture.

In 1841 he bought 130 acres of poor, wet heathland in Tiptree, in one of the least productive districts in Essex, and proceeded to improve it by such means as deep drainage, removing hedges and trees, redesigning buildings and the use of steam-powered machinery. He persevered until his model farm turned a handsome profit. Mechi was exceptional amongst agricultural improvers for publishing details of his experiments in books, pamphlets and newspaper articles. He even published annual statements of his farm’s income and expenditure, explaining his failures as well as justifying his successes. His well-known publication How to Farm Profitably (1857) had, in various forms, a circulation of thousands of copies. Sadly, his career ended in disappointment, as the failure of his banking interests deprived him of the funds needed for his style of farming, and this, together with the effects of several bad seasons at Tiptree Hall Farm, led to the liquidation of his affairs shortly before his death.

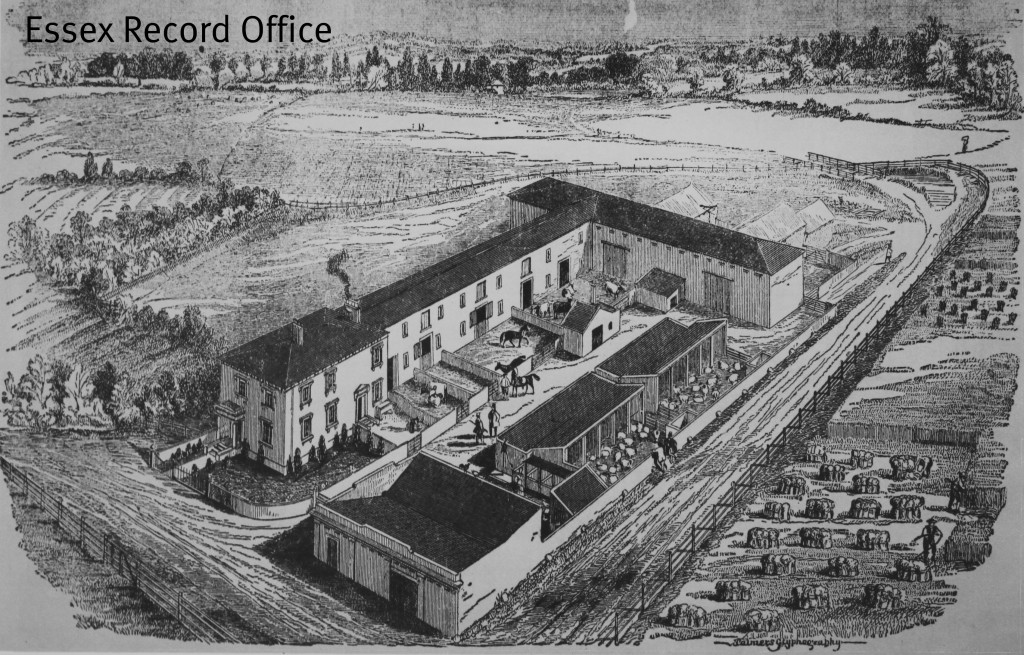

Tiptree Hall Farm one year after Mechi designed it. The main buildings are on the north and east sides, giving shelter from the coldest winds. The barn contained a horse-powered threshing machine. When not driving the threshing machine, the horse gear could be used to drive a chaff-cutter or corn mill. Within a year Mechi had decided to exchange horse power for steam power.

Marconi’s – the world’s first purpose-built radio factory

Guglielmo Marconi established the world’s first wireless factory in a former silk mill in Hall Street in Chelmsford in 1898, when he was aged just 23. Chelmsford was chosen because Marconi needed electrical power, and in the 1890s Chelmsford was the place to be for electricity, thanks to the pioneering work of R.E.B. Crompton and Frank Christy.

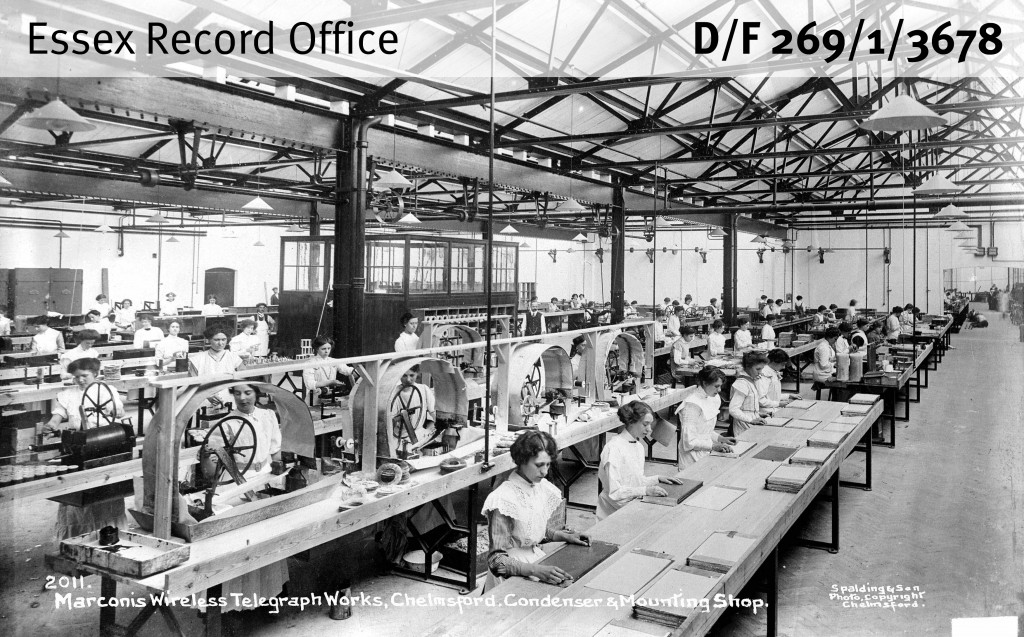

In June 1912, a replacement 70,000 square foot purpose-built factory was opened in New Street. The factory was completed in an astonishing 17 weeks by a workforce of over 500 people. The factory provided employment for thousands of men and women; although the machine shop remained the preserve of men, women were employed for the more delicate aspects of the production of wireless transmitters.

Marconi wireless equipment was used by ships and coastal stations to communicate with one another in Morse code. During the First World War, operators at New Street intercepted German radio transmissions for the British government, and Marconi engineers also developed the technology for ground-to-air communication with aeroplanes. During the Second World War, Marconi’s played a crucial role in the development of radar.

After the First World War, engineers at New Street began to experiment with wireless voice transmissions. The first publicised entertainment broadcast in Britain took place at the factory in June 1920, when Dame Nellie Melba performed. Her singing could have been picked up anywhere across Europe by someone with receiving equipment. By 1931 there was one wireless licence for every three homes in the country.

Shortly after the New Street factory opened, local photographer Fred Spalding took a series of photographs of the new facility. Click here to view more of the photographs from a previous blog post.

Check back here tomorrow for more to accompany Michael’s visit to Tilbury.