In this guest blog post, Denwood Holmes writes for us from Bangkok about his research in the Essex archives…

Greetings from Bangkok, where I hope I have the distinction of being among the ERO’s more far-flung correspondents.

As an Ottoman art historian-turned-PR consultant, genealogy has been a means to maintain my interest in archival research while languishing in the private sector. Tracing my American patrilineal ancestry started out easy: most colonial New England descents are fairly well documented, and armed with the name of a great-great grandfather, two articles on the descendants of John Holmes, gentleman, Messenger of the Plymouth Colony Court by distinguished genealogist (and cousin) Eugene Stratton quickly took me back twelve generations. The original Mr. Holmes was by all accounts something of a rogue, frequently cited for drunkenness, and the executioner of Thomas Granger, the first person hanged in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, for unlawful congress with animals.

After that the going got tougher. American genealogists have historically been content to end their research with arrival in the New World (why ever would we go further?), but to do with my teenage years spent in the UK, and inspired partly by David Hackett Fischer’s book Albion’s Seed, I became determined to the trace the Great Leap across the pond.

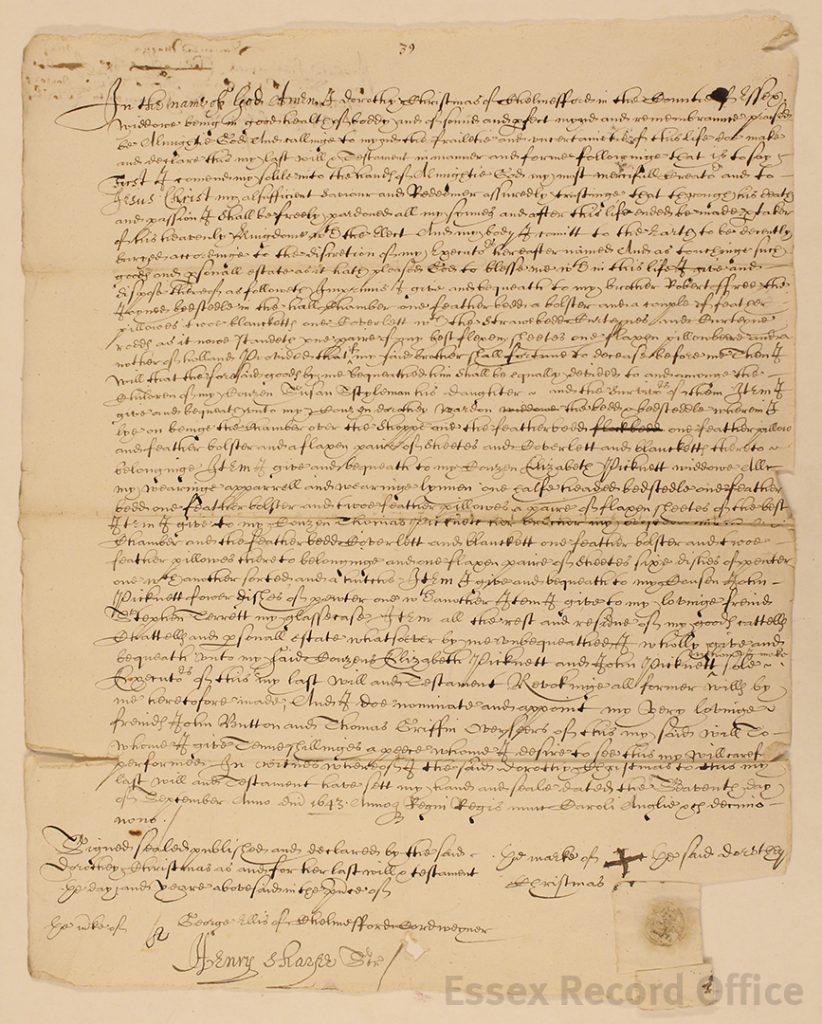

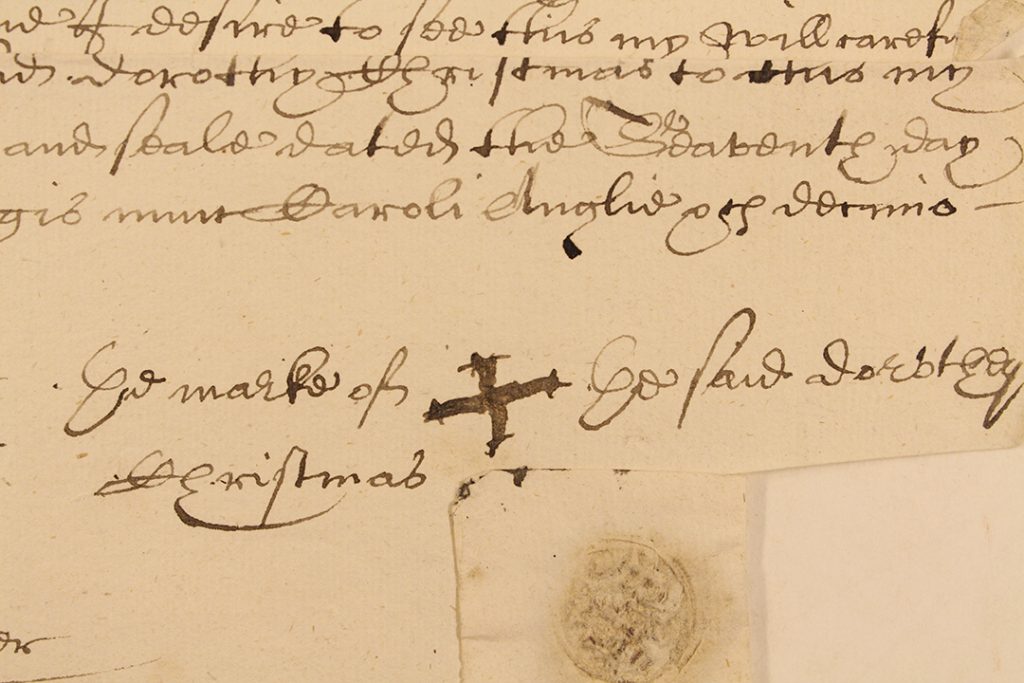

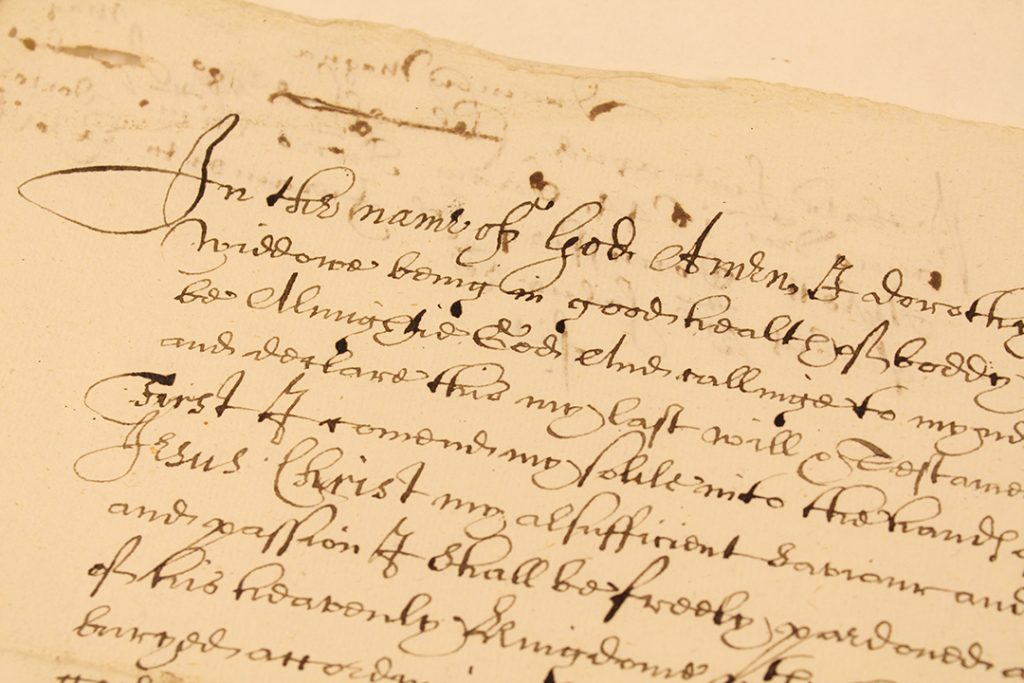

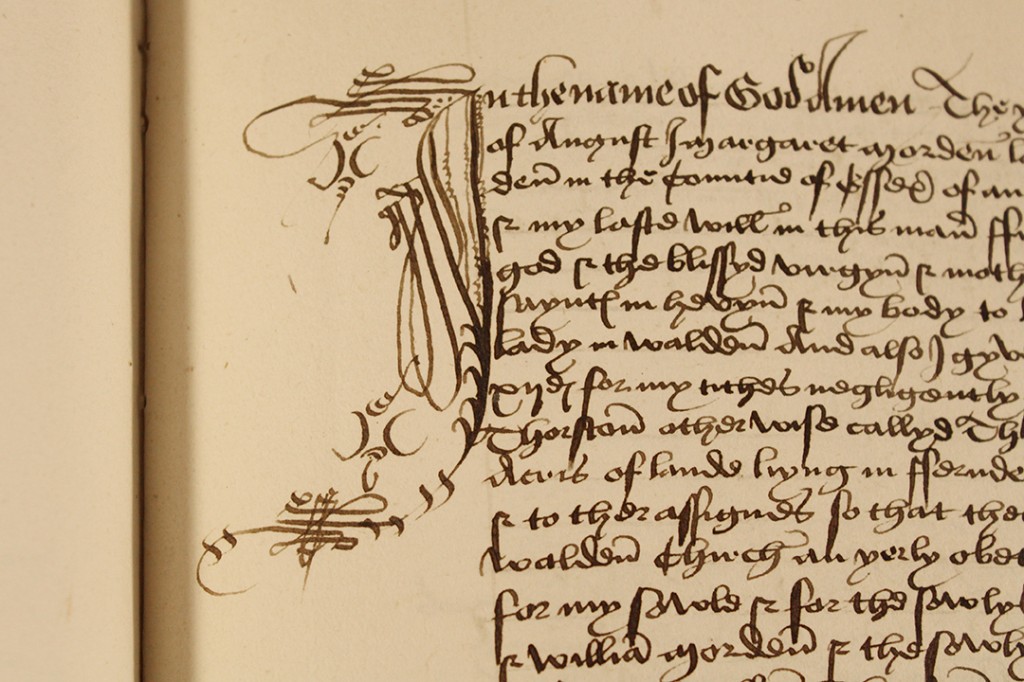

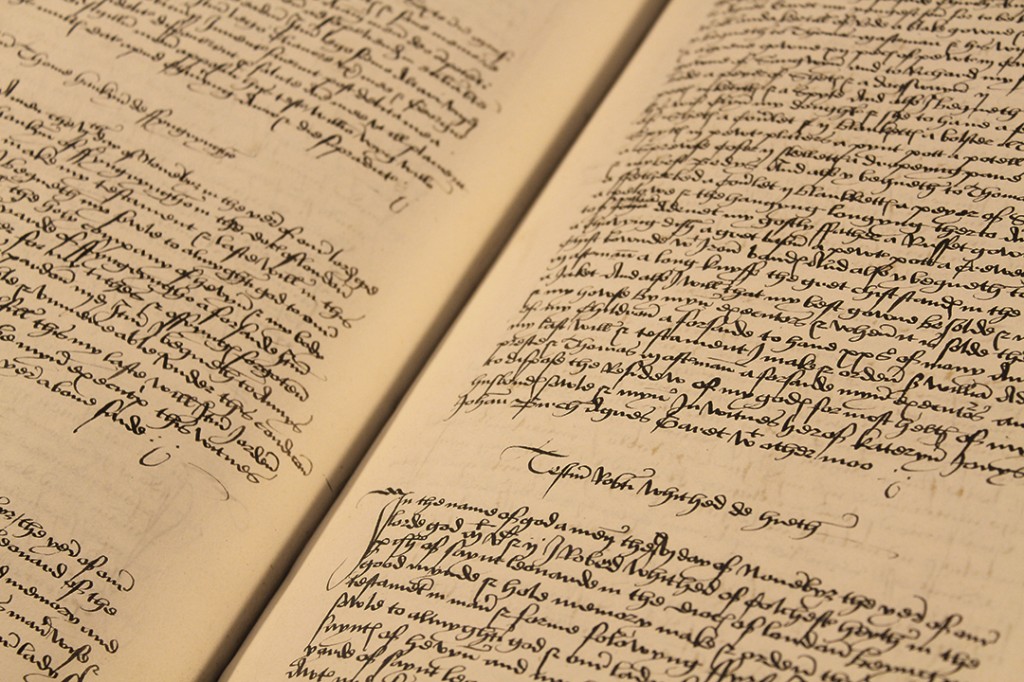

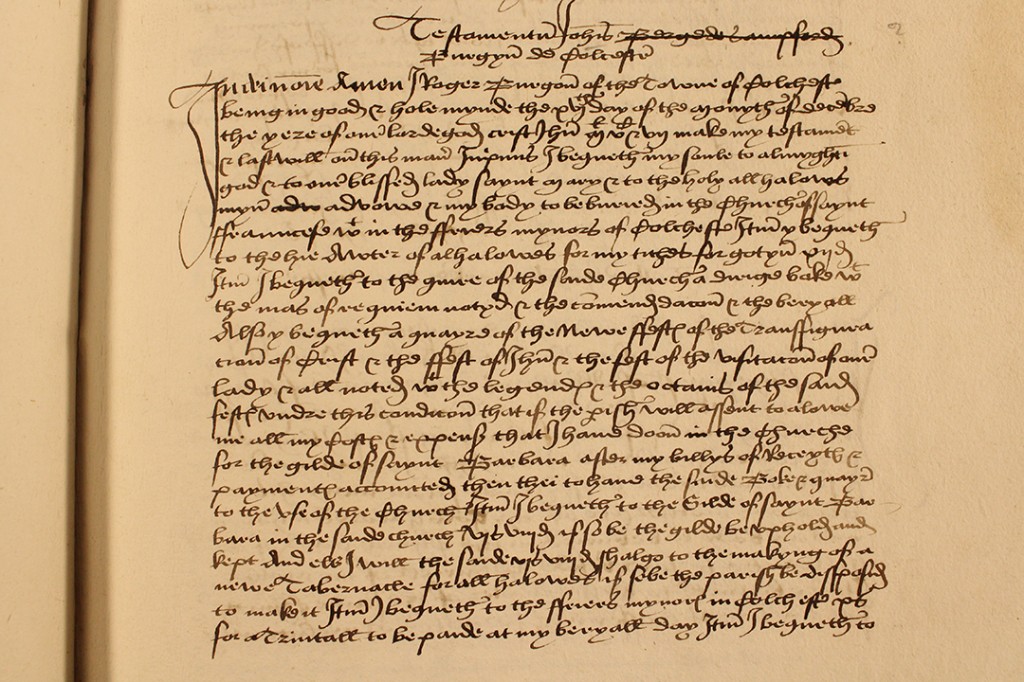

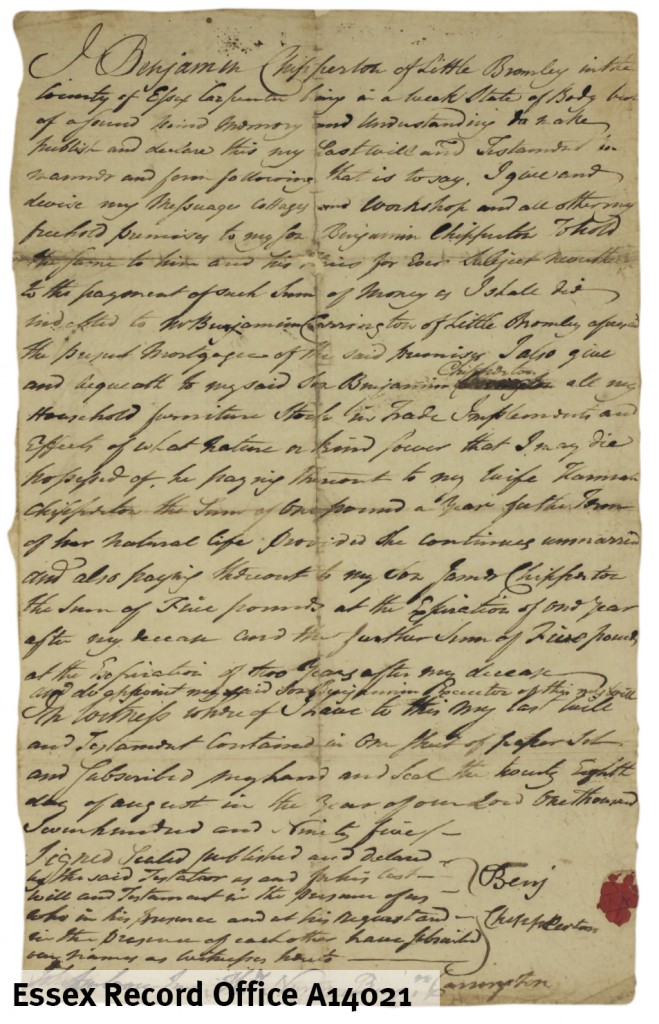

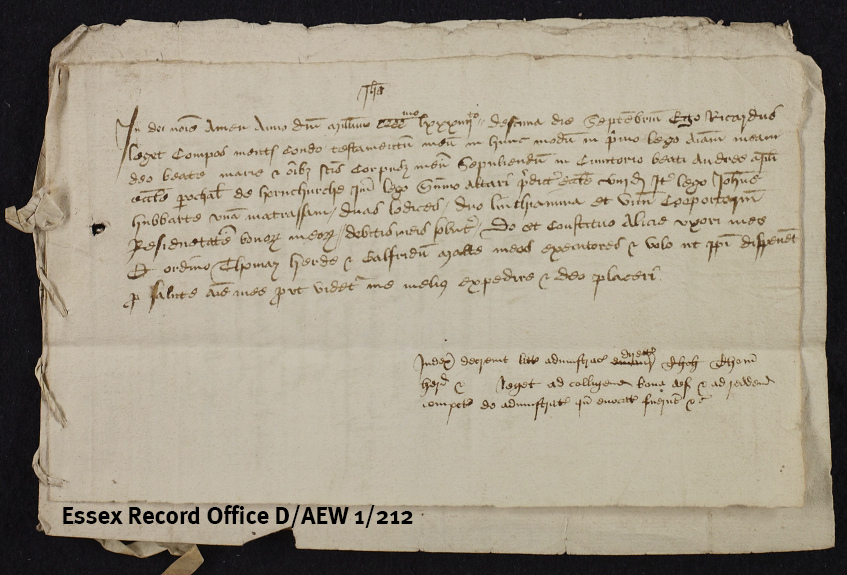

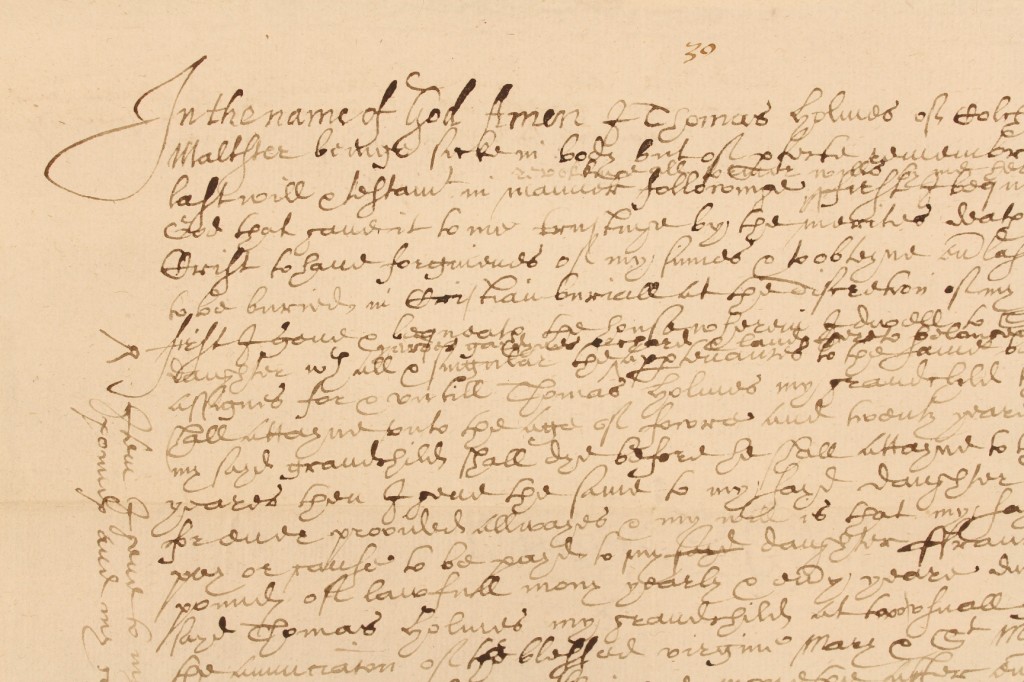

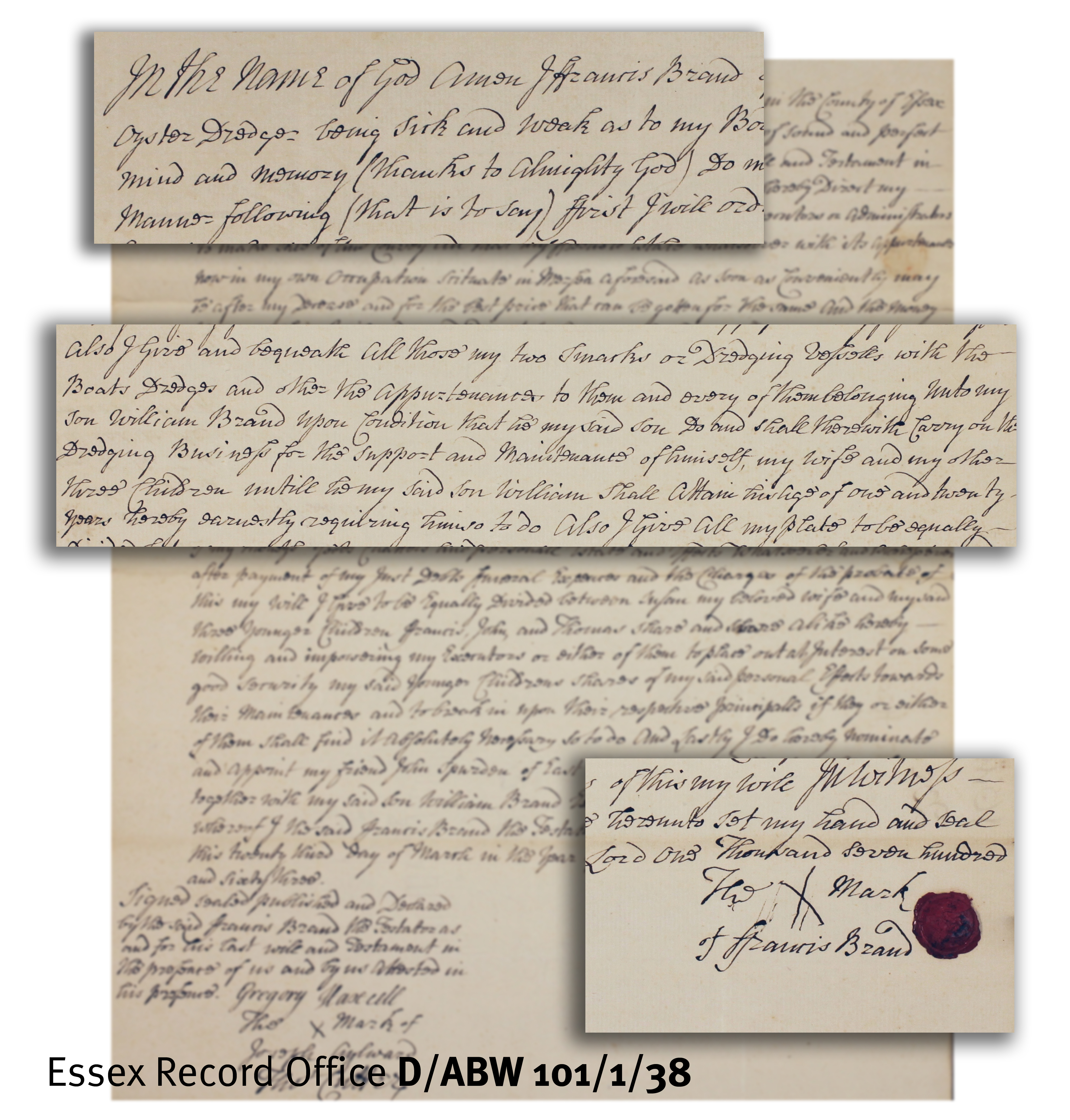

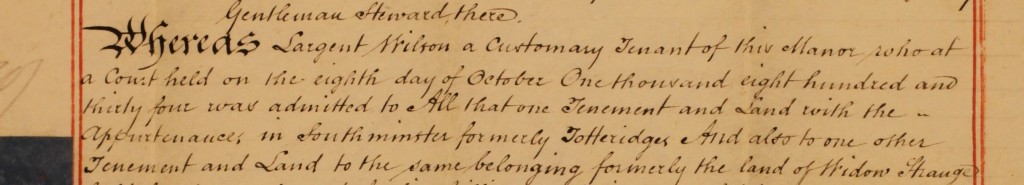

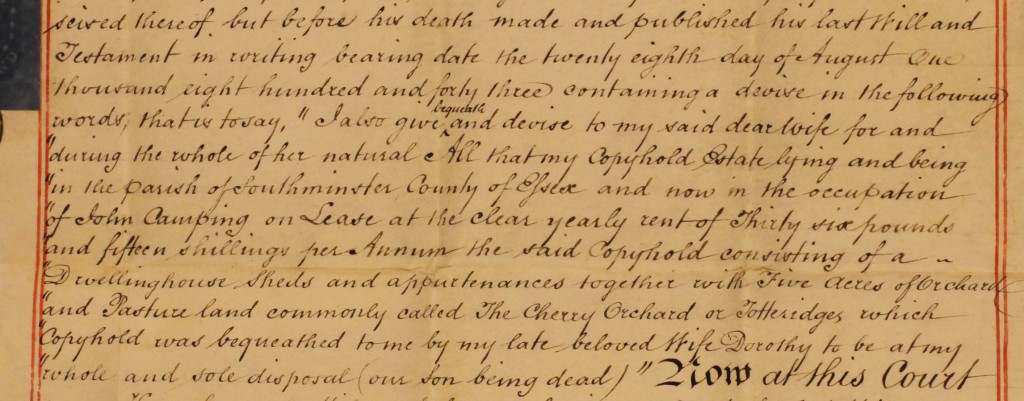

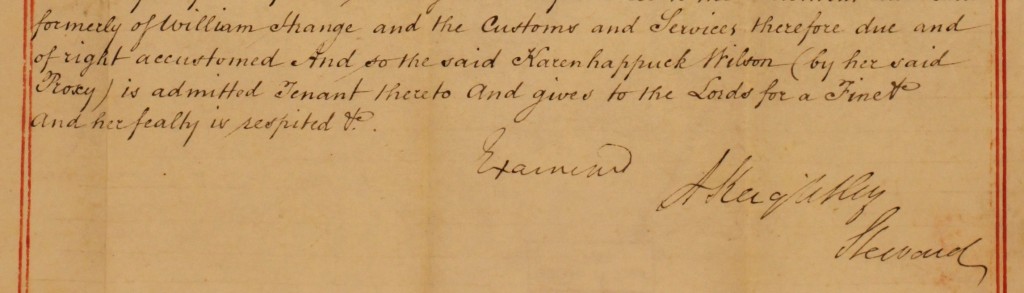

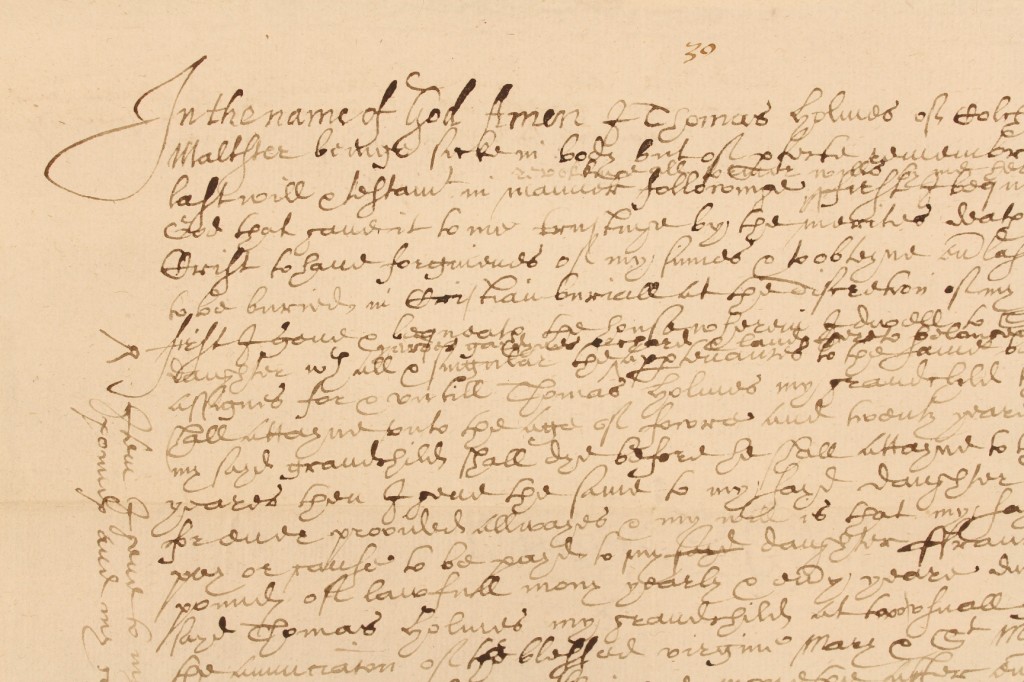

It wasn’t entirely tabula rasa: George Mackenzie, in his Colonial Families (1925) cites a Thomas Holmes of Colchester as John’s father, but without further reference. Thomas’ will, dated 1637, is preserved in ERO (D/ACW 12/225): gentleman alias maltster alias gaoler of Colchester Castle, he leaves “five pounds, my corslet, my pike, and all my armour” to his son John.

Will of Thomas Holmes of Colchester, 1637 (D/ACW 12/225)

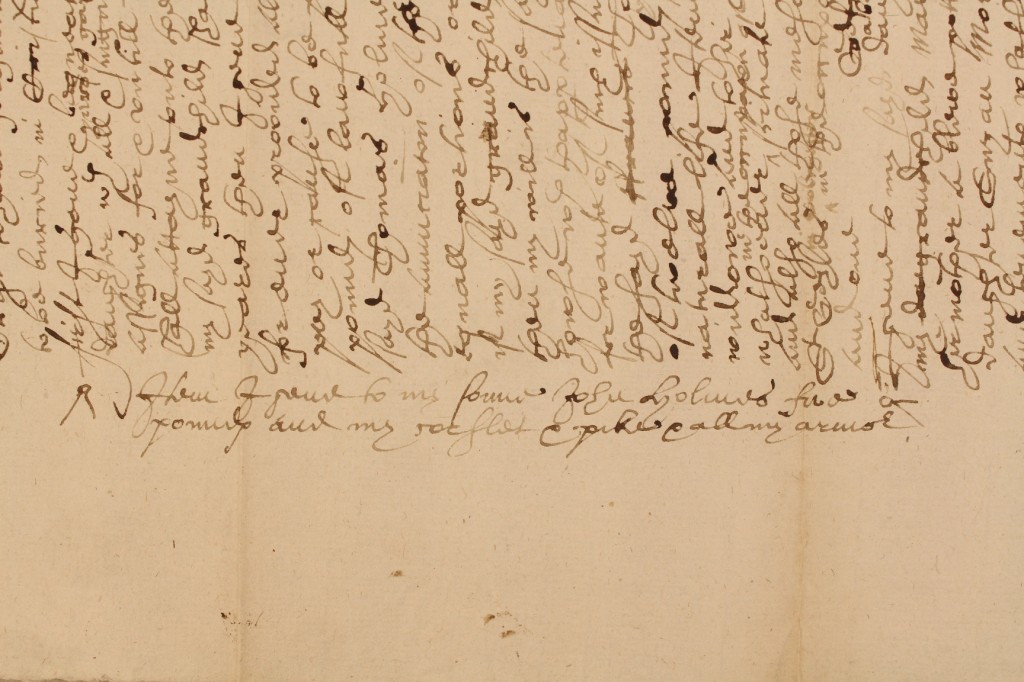

Thomas left corslet, pike and armour to his son John (D/ACW 12/225)

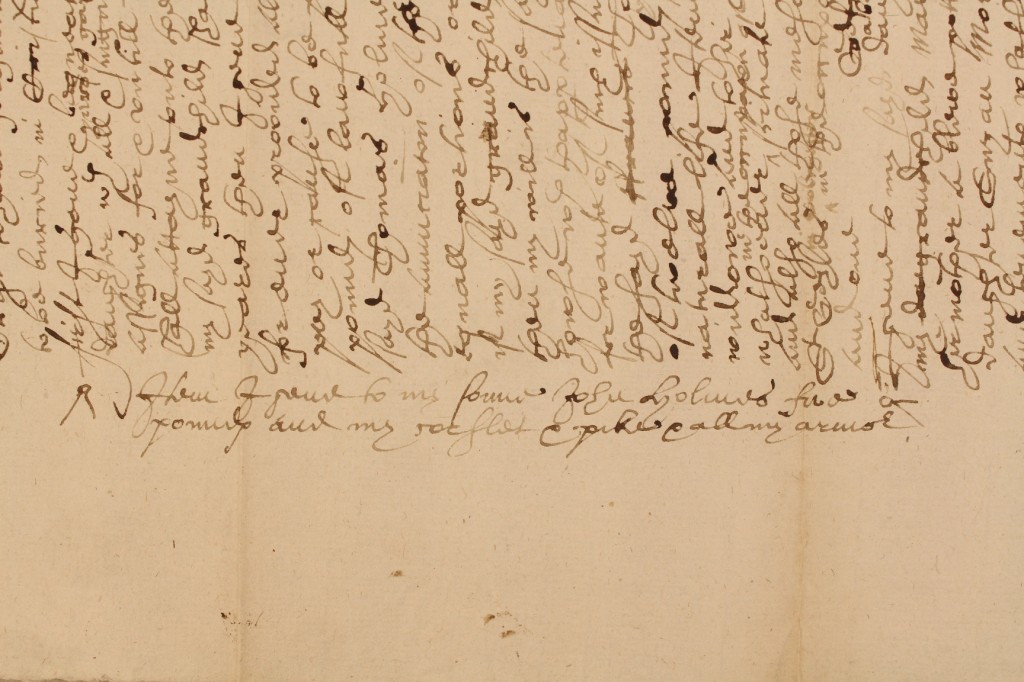

The will also mentions a daughter, Susan Mor(e)ton, the widow of Tobias Moreton, gent., of Little Moreton Hall, a half-timbered manor house which still stands in Cheshire. Susan’s will, unearthed by chance in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, confirms Mackenzie’s assertion: she mentions her nephews (John’s sons) Thomas (who remained in Colchester), John, and Nathaniel, my great x8 grandfather.

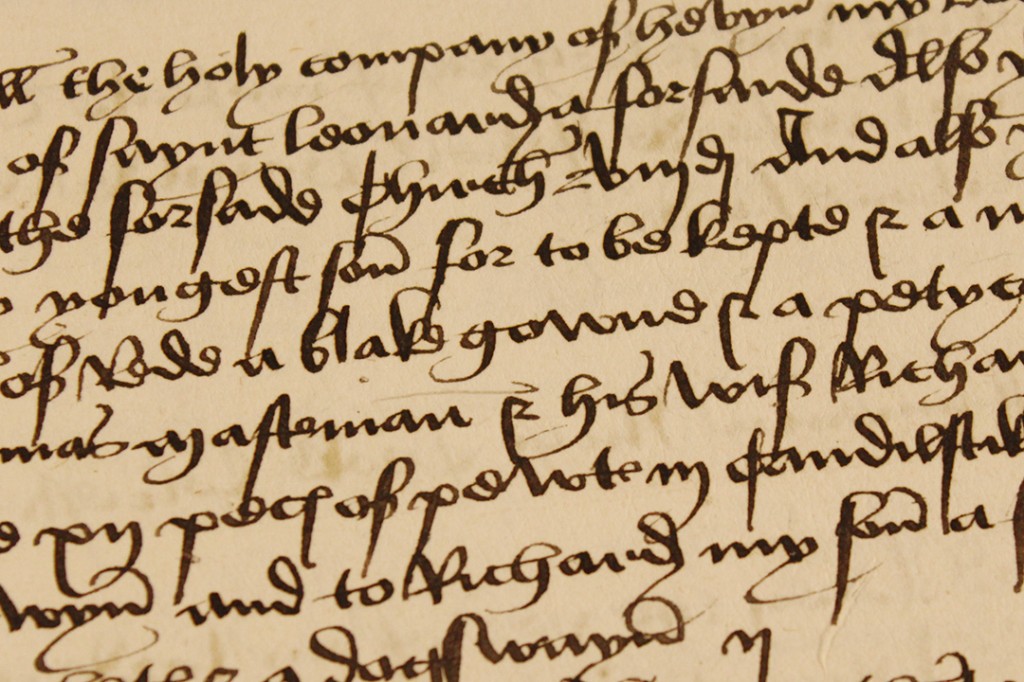

Extract from Thomas Holmes’s will mentioning his daughter, Susan Morton (D/ACW 12/225)

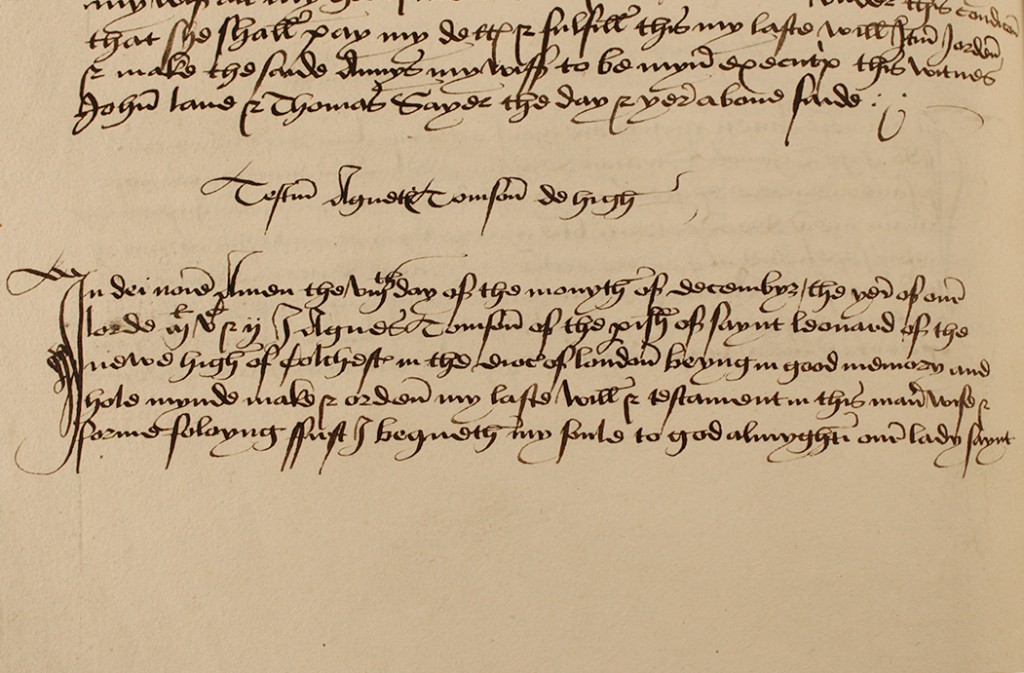

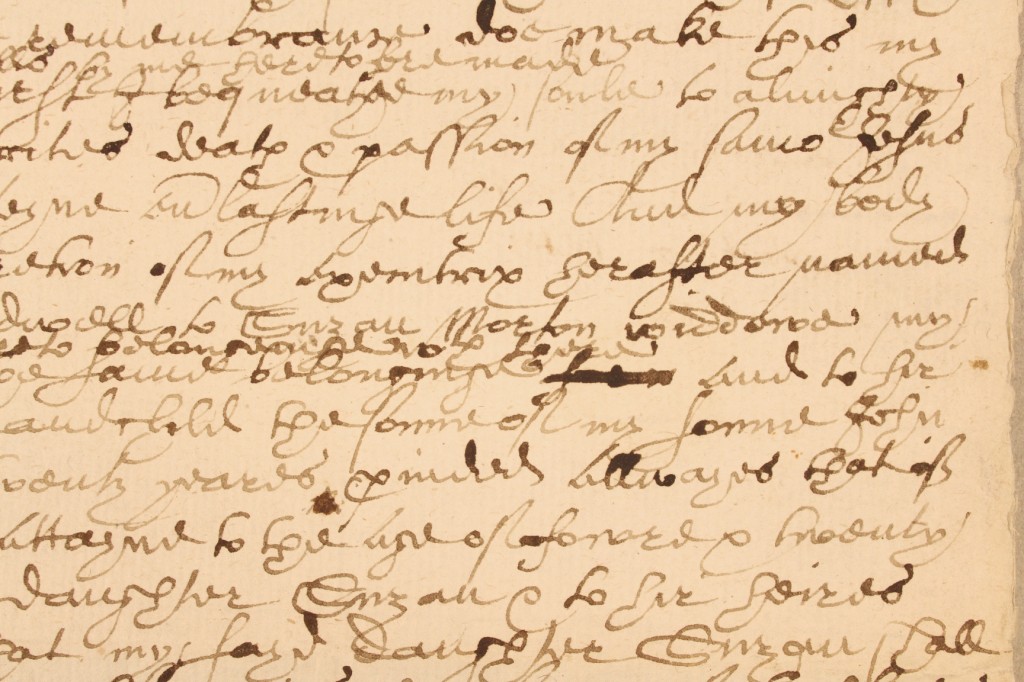

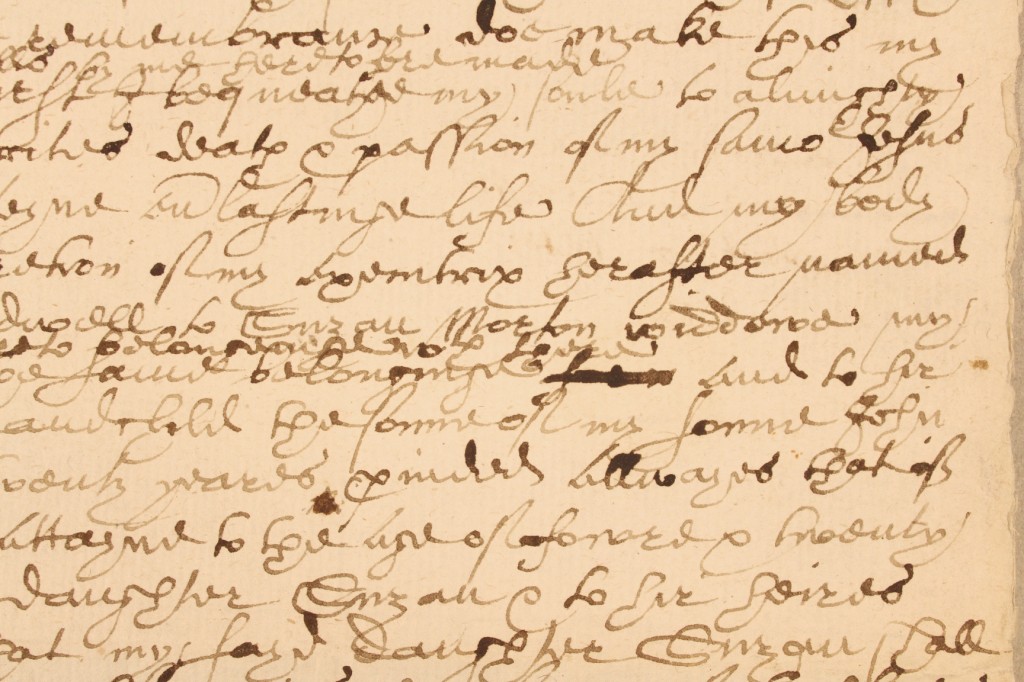

Along with a number of noted Colchester Puritans, the will is witnessed by George Gilberd, esquire, brother of William Gilberd/t, physician to Elizabeth I.

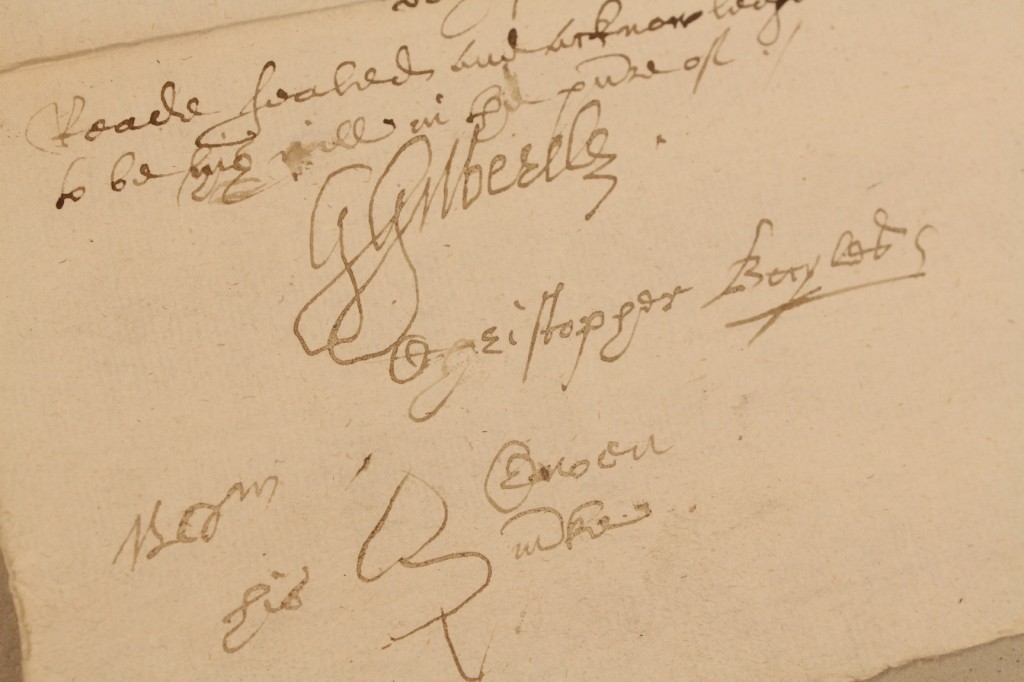

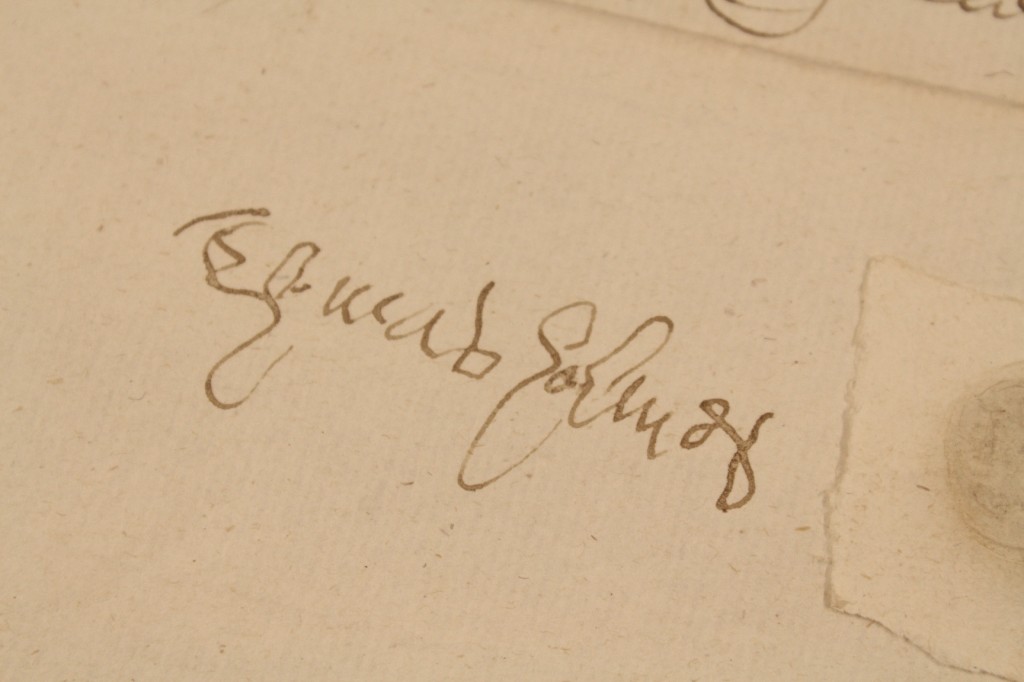

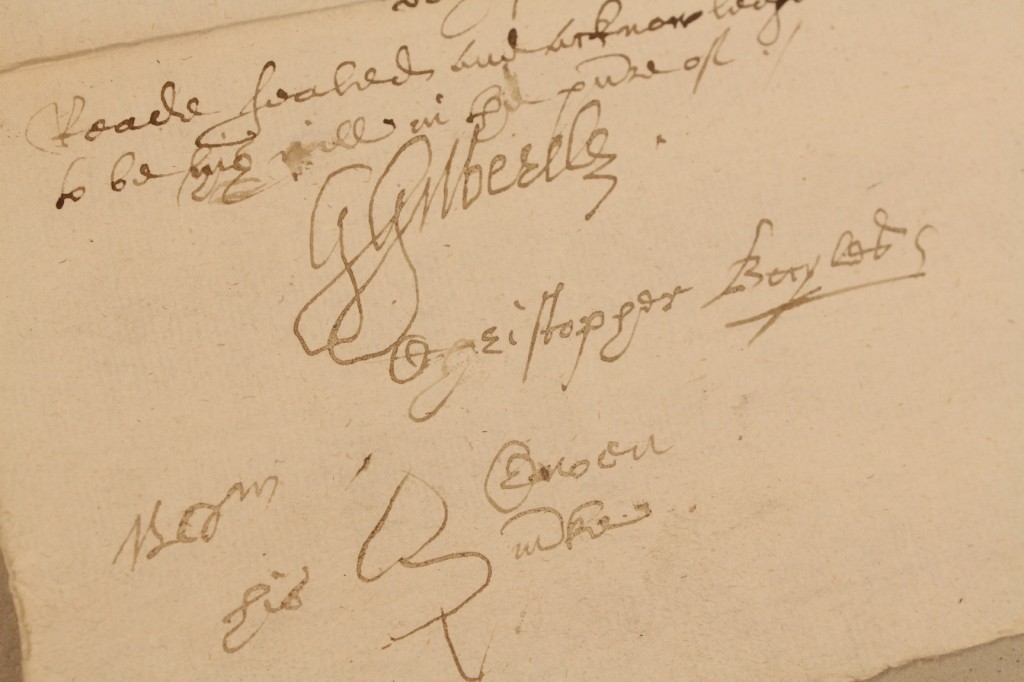

Signatures of witnesses to Thomas Holmes’s will (D/ACW 12/225)

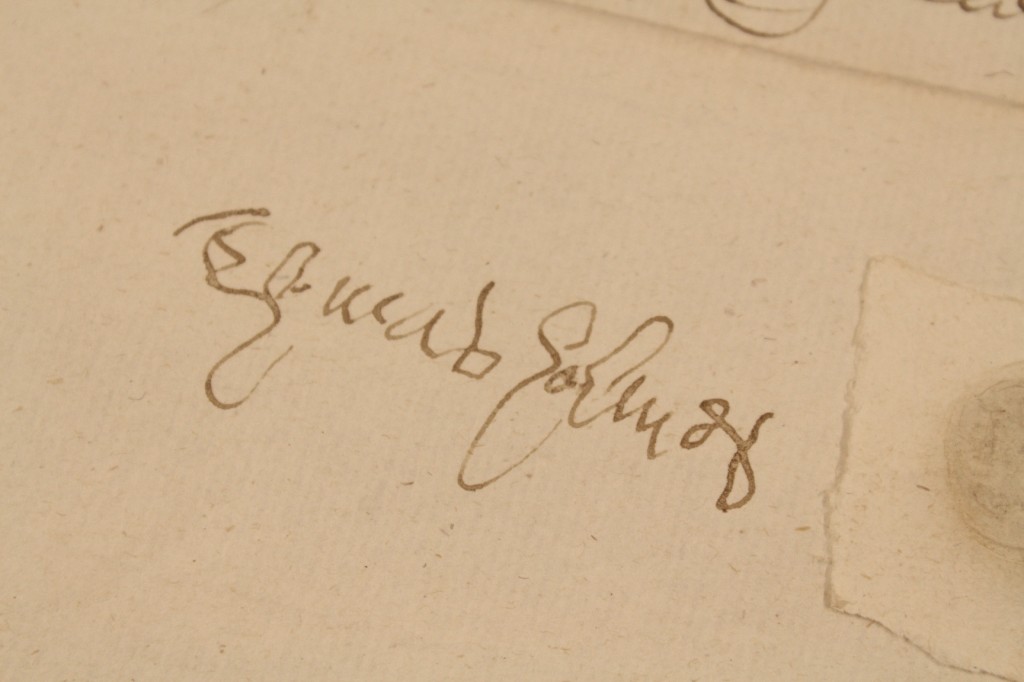

Thomas Holmes’s signature at the end of his will (D/ACW 12/225)

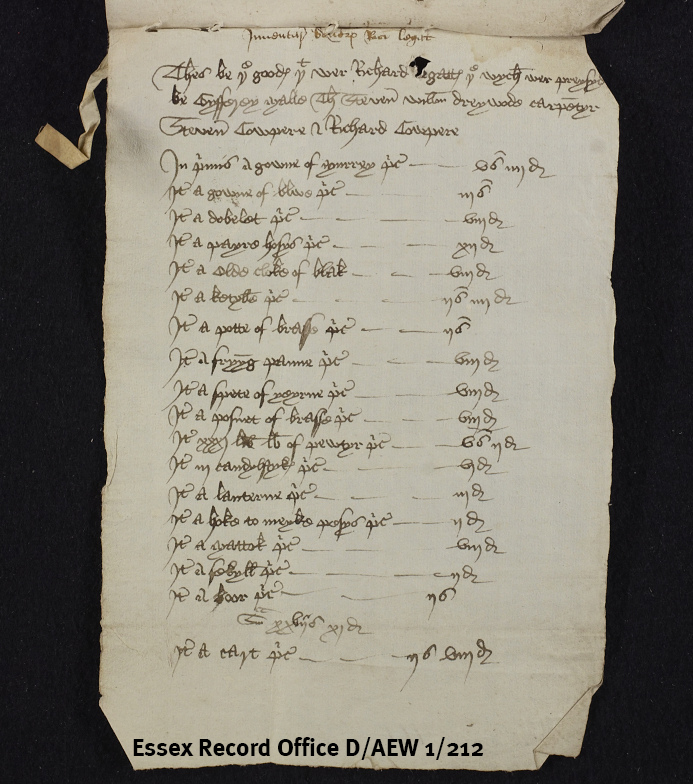

The Holmes family – clearly middling Puritan parish gentry – were not native to Colchester: according to the Red Parchment Book of Colchester, Thomas’ grandfather Thomas, draper, was sworn a burgess in 1543, and is described as being of Ramsden Bellhouse. There the trail dwindles. The ERO will of Thomas Holme of Ramsden Bellhouse of 1514 mentions a brother, John, a tailor, but little more. Finally, in the Feet of Fines for Essex, we find the last signpost to date:

“Hilary and Easter, 14 Henry VII (1499); William Holme, Humphrey Tyrell, esquire, Thomas Intilsham, “gentilman”, William Howard, clerk, William Bekshyll and William Rede, plaintiffs. John Choppyn and Joan his wife, daughter and one of the heirs of John Dawe, deceased, defendants. A third part of a moiety of 1 messuage, 60 acres of land, 10 acres of meadow, 30 acres of pasture and 10 acres of wood in Ramesdon Belhous, Dounham, Wykford, Ronwell, and Suthhanyfeld. Defendant quitclaimed to plaintiffs and the heirs of William Holme. Consideration 40 marks.”

Certain prosopographical observations can be made here. Humphrey Tyrell of Warley was a younger son of the Tyrells of Heron, probably a nephew of the Sir James executed for the murder of the Princes in the Tower. Howard was his clerk. Hintlesham was an MP for Maldon, and Rede was probably the nephew and heir of Sir Bartholomew Rede, Mayor of London. All were in the circle of John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford. The identity of William Holme remains a mystery; there are two or three of the name active in London at around the same time, all probably in the cloth trade. Here the trail ends, for the time being: any thoughts or suggestions on the part of the ERO community as to how to proceed are much appreciated; I can be reached at Denwood_Holmes@yahoo.com.

I conclude with a special thanks to Allyson Lewis, Katharine Schofield, and all of the staff at ERO for their help and support which regularly goes above and beyond the call of duty, extending unto providing me with pencil-rubbings of seals by mail here in Bangkok; having worked in archives from London to Damascus I say unequivocally that ERO is lucky to have you.