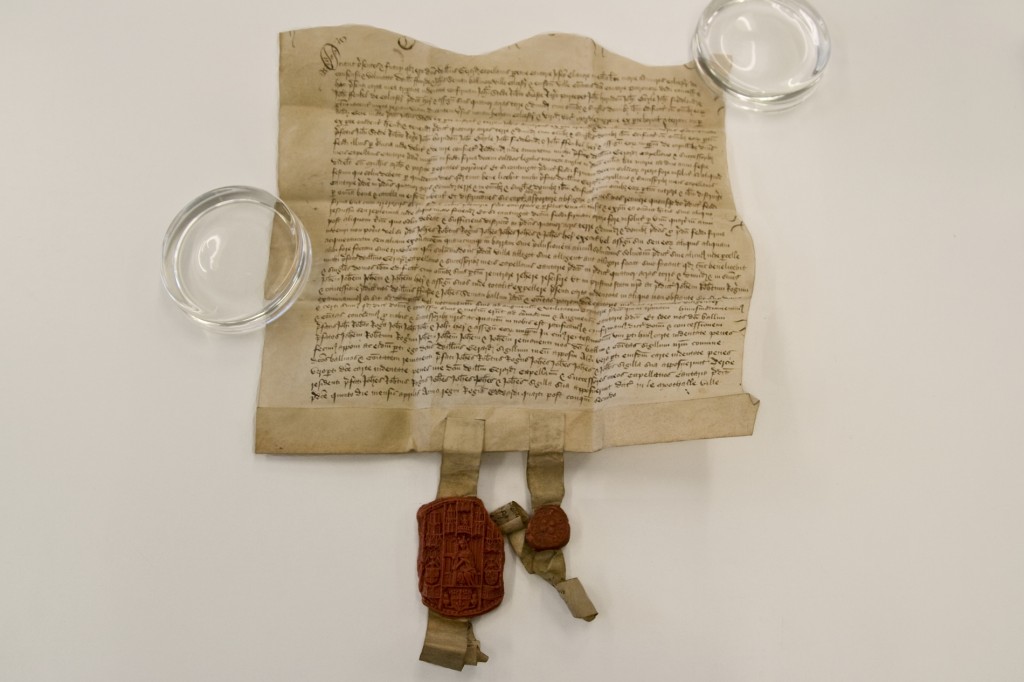

One of the joys of working in an archive is the potential every day holds for coming across something beautiful or interesting in our collection. Last week’s star find was a medieval deed, D/DRg 6/5, or more specifically, one of the wax seals attached to it.

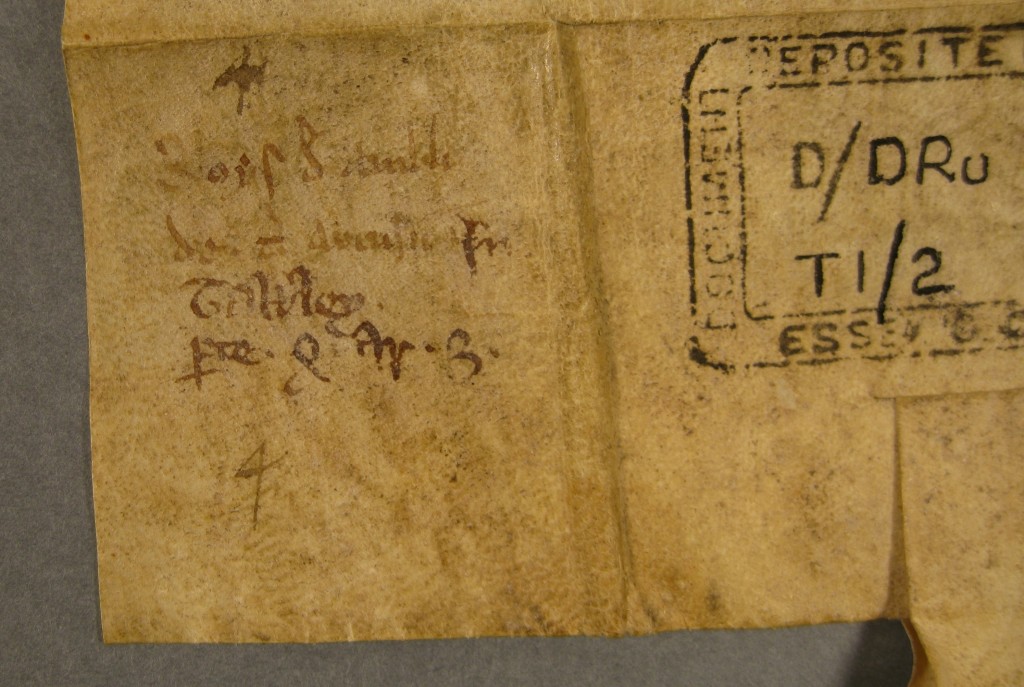

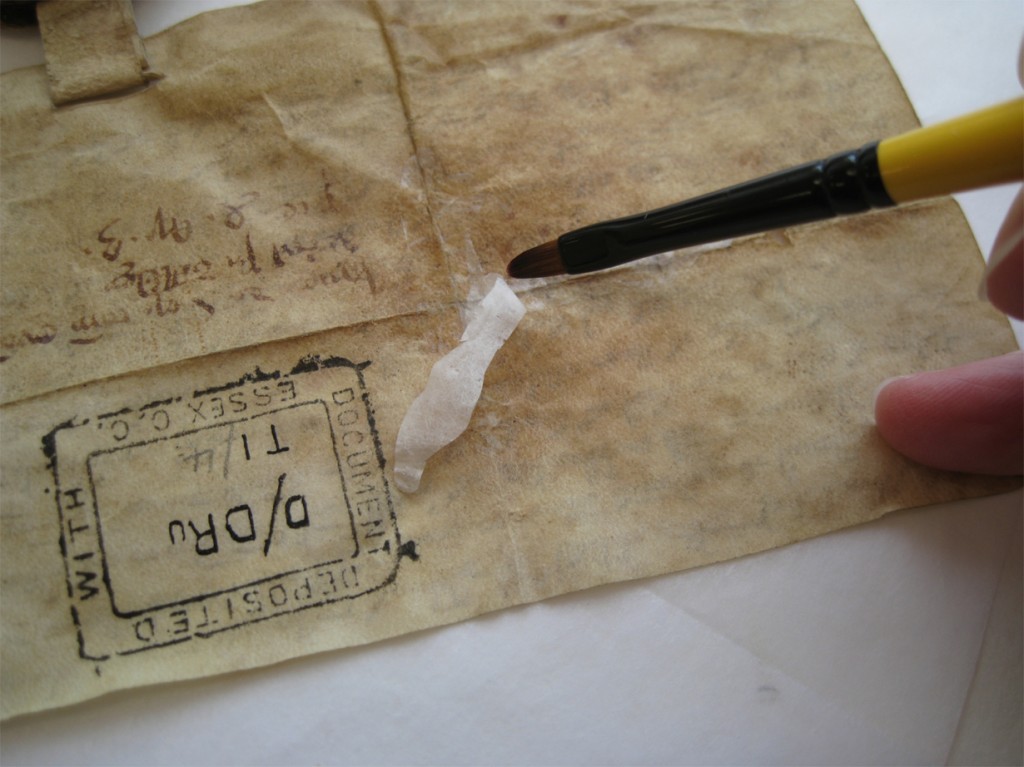

The document was in the Conservation Studio with a group of other similar documents all in need of a bit of attention and better storage to protect their fragile wax seals.

The deed dates from 5 April 1462, and is part of the collection of Charles Gray of Colchester, an eighteenth-century lawyer, antiquarian and MP, and major figure in Colchester’s history. Gray assembled a large collection of medieval deeds relating to Colchester, catalogued as D/DRg 6 and D/DRg 7; the earliest dates from 1317 (D/DRg 6/2).

This particular deed grants land to William Gerard, Chaplain of the Chantry of Joseph Elianore in the church of St Mary-at-the-Walls in Colchester. Chantry chapels were endowed by individuals who left money to pay for a priest to pray for their souls to help them on their way to heaven; in this case for the soul of Joseph Elianore, a Bailiff of Colchester, and various members of his family and other associates.

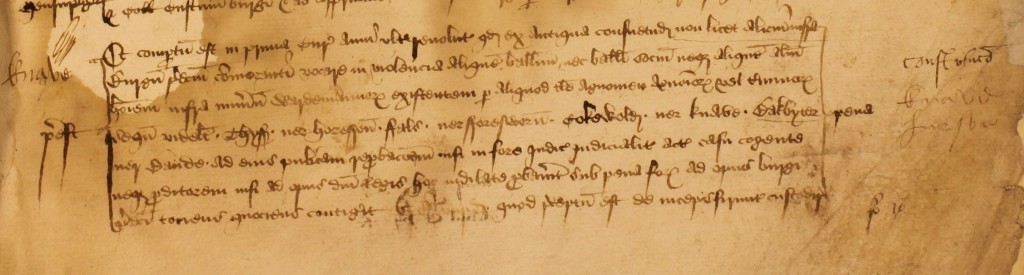

The land which Gerard was being granted was 4 and a half acres, with buildings on, next to the highway leading across New Heath, bordered on the north by ‘Magdleyngreene’, on the south by land formerly owned by Robert Gete and now by John Stede, on the east by land owned by John Auntrous, and on the west by the lane leading towards ‘Bournepond Mill’ or ‘Boornemelle’.

As we mentioned recently, this is one of the advantages of using deeds in your research; they can list who owns not only the piece of land in question, but the land around it, and sometimes even previous owners.

The document has two wax seals attached to it, one very small, one medium sized. Seals were a form of security, often used to hold a letter or envelope closed, so that it could not be opened or tampered with until delivered to the intended recipient. Wax seals were also attached to the bottom of documents, as in this case, when they served as a means of authentication.

The larger of the two seals attracted our attention because the impressions in the wax are so deep and the imagery so detailed. A little investigation showed it to be the second Common Seal of the Borough of Colchester.

The obverse of the seal shows St Helena, the patron saint of Colchester. St Helena, the mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine, was believed to have been born in Colchester, the daughter of King Coel. She reputedly travelled to the Holy Land, and found relics of the True Cross and the burial place of the Magi, which is why Christian iconography depicts here (as here) with the cross.

Below St Helena are the borough arms, which were granted by Henry V in 1413. These again reflect St Helena’s influence, showing the True Cross and the crowns of the Magi. On each side of St Helena are niches containing angels holding shields; on the left bearing a cross, and on the right the fifteenth-century royal arms. In the niche above St Helena is a half-length Christ. The reverse of the seal shows a medieval depiction of a castellated town, with a river in front of it crossed by a bridge.

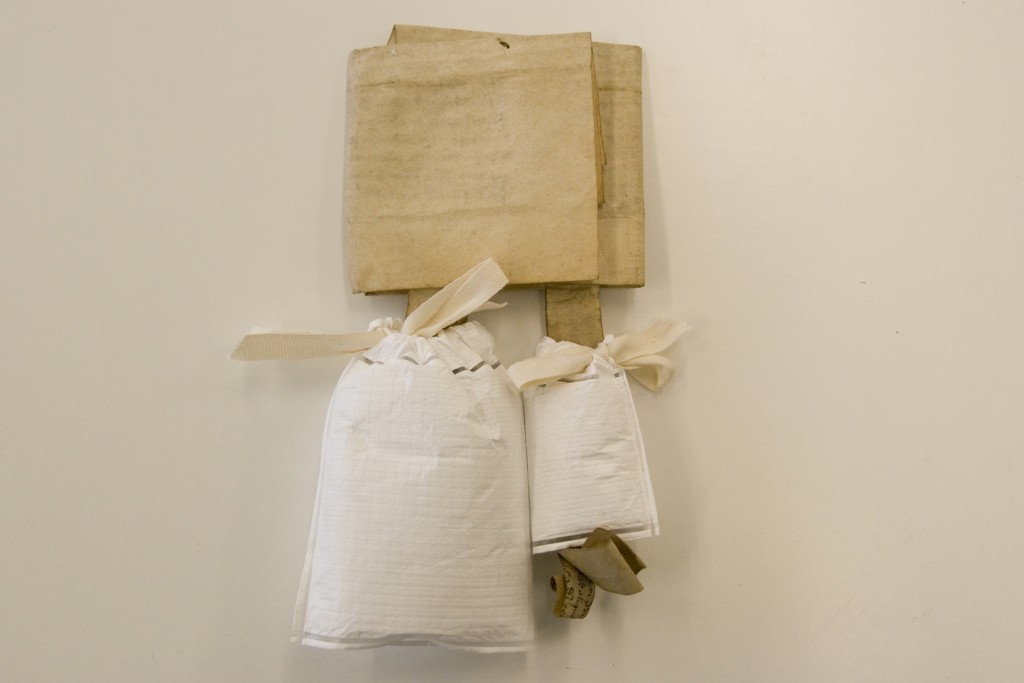

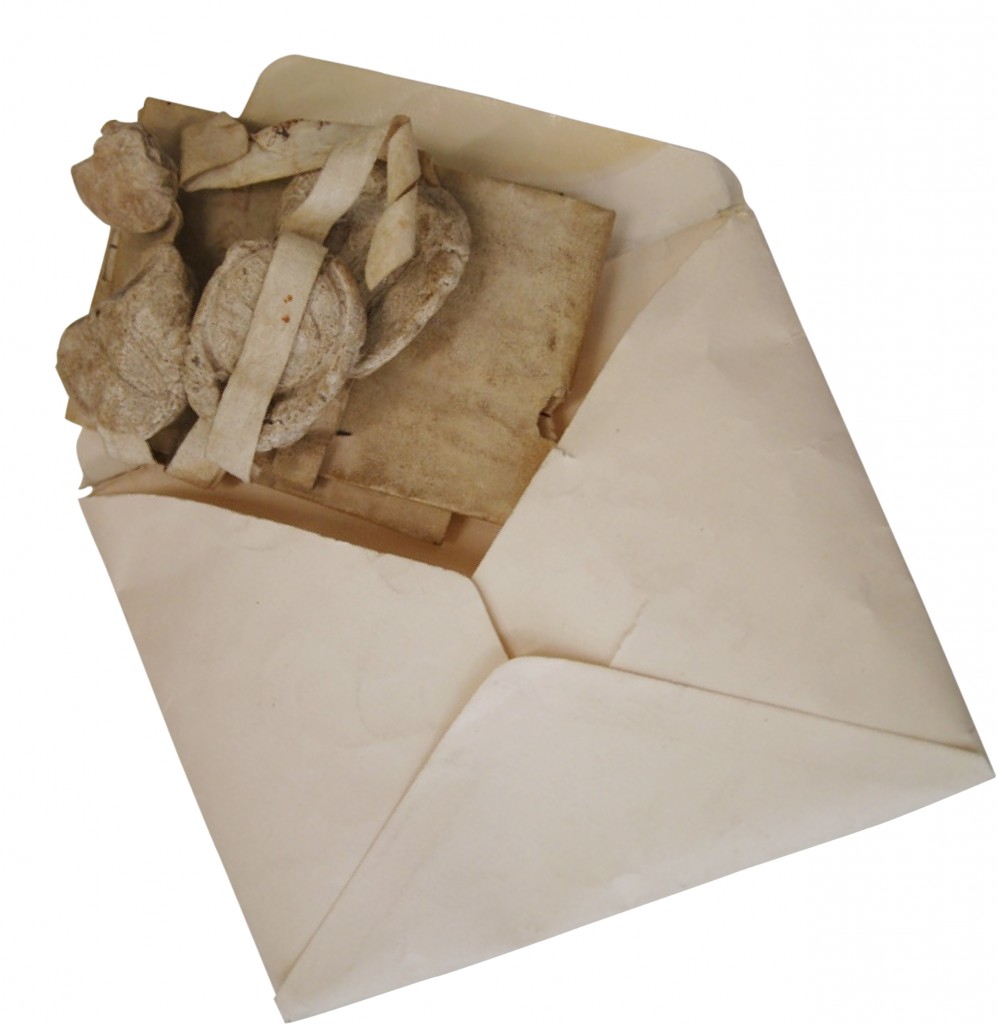

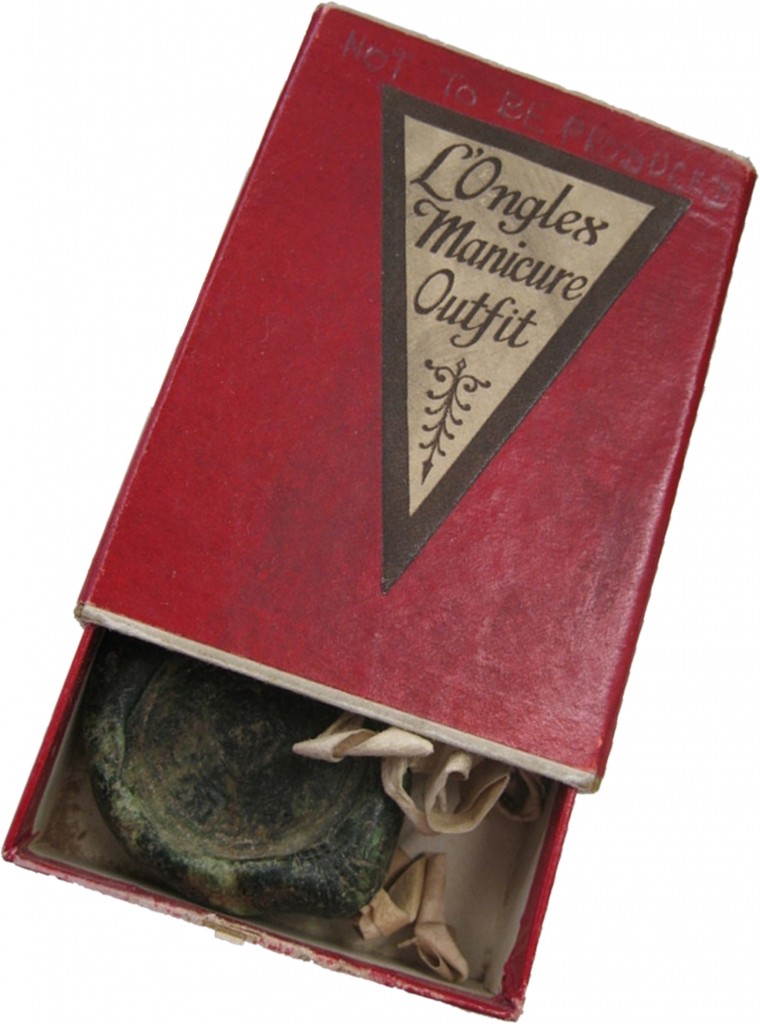

Both seals attached to the deed have been cleaned by our Conservators with a mild detergent called synpernoic A7 and distilled water, before being stowed in their own custom-made cushioned bags. These little bags are made from Tyvek with a polyester wadding. The materials are cut to size, and then heat sealed around the edge. The whole document is then wrapped in acid-free manilla before being stored in one of our special archival quality boxes.

Stored in protective wrappers in our climate-controlled repositories, this 671 year old document – and its wax seals – should survive for many years to come.