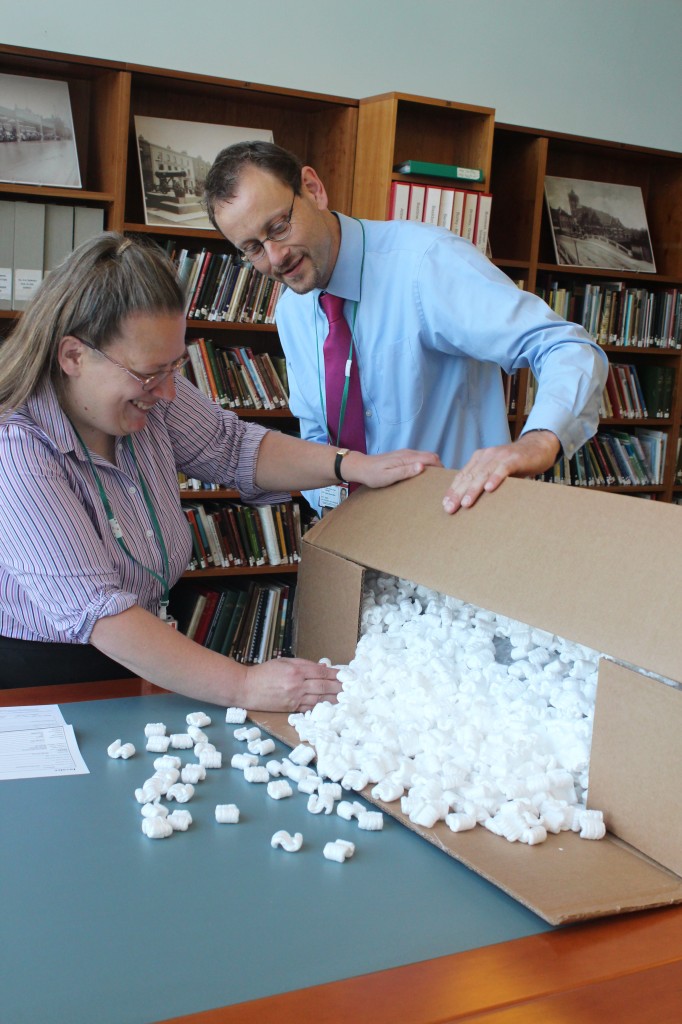

The Essex Record Office recently hosted the launch for the database of ‘The People of 1381’ (an Arts and Humanities Research Council funded project). As part of the launch

Katharine Schofield and Diane Taylor curated a surprise pop-up exhibition of relevant sources kept at the ERO. In this blog Dr Herbert Eiden (Research Assistant for ‘The People of 1381’ project) reflects on why one of these documents holds particular interest.

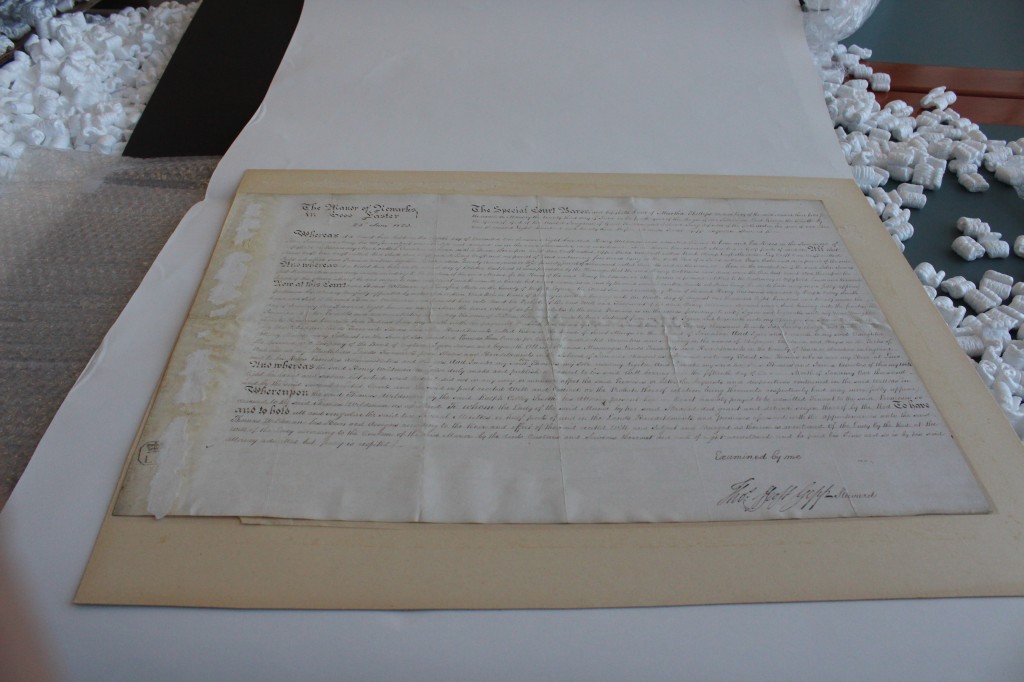

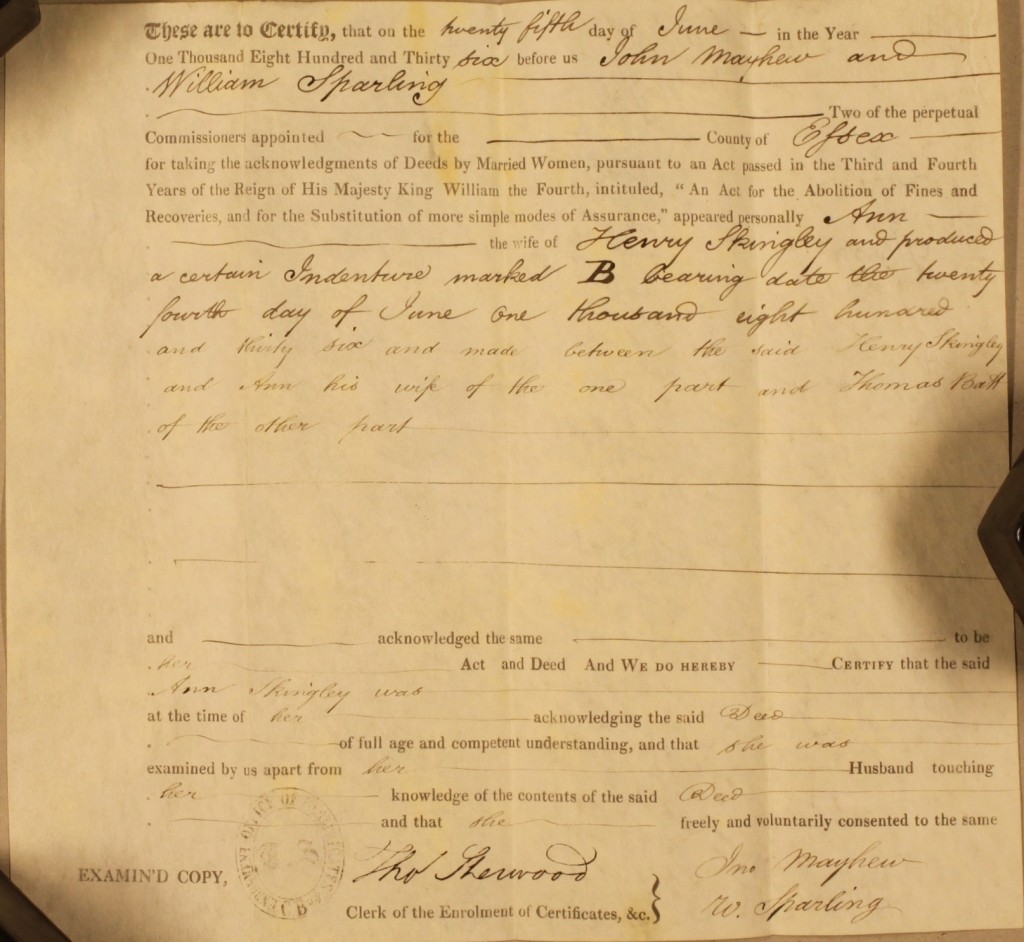

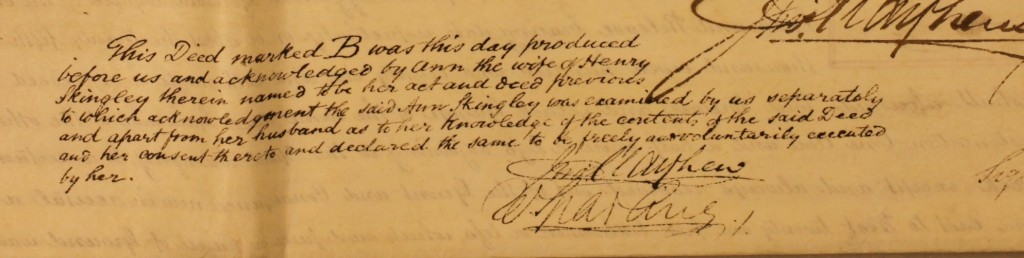

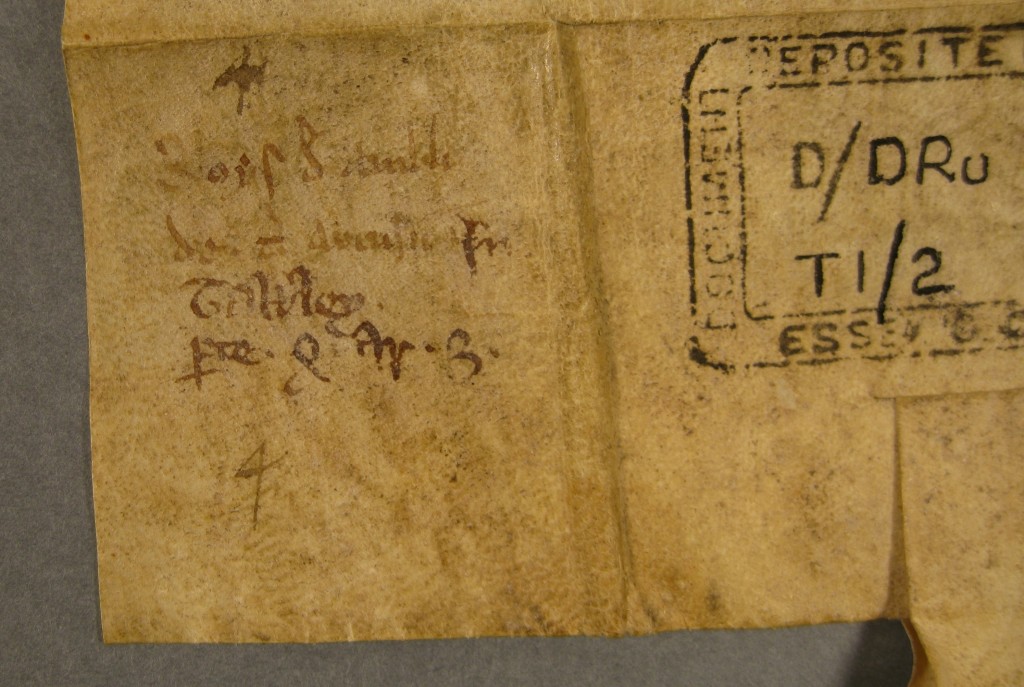

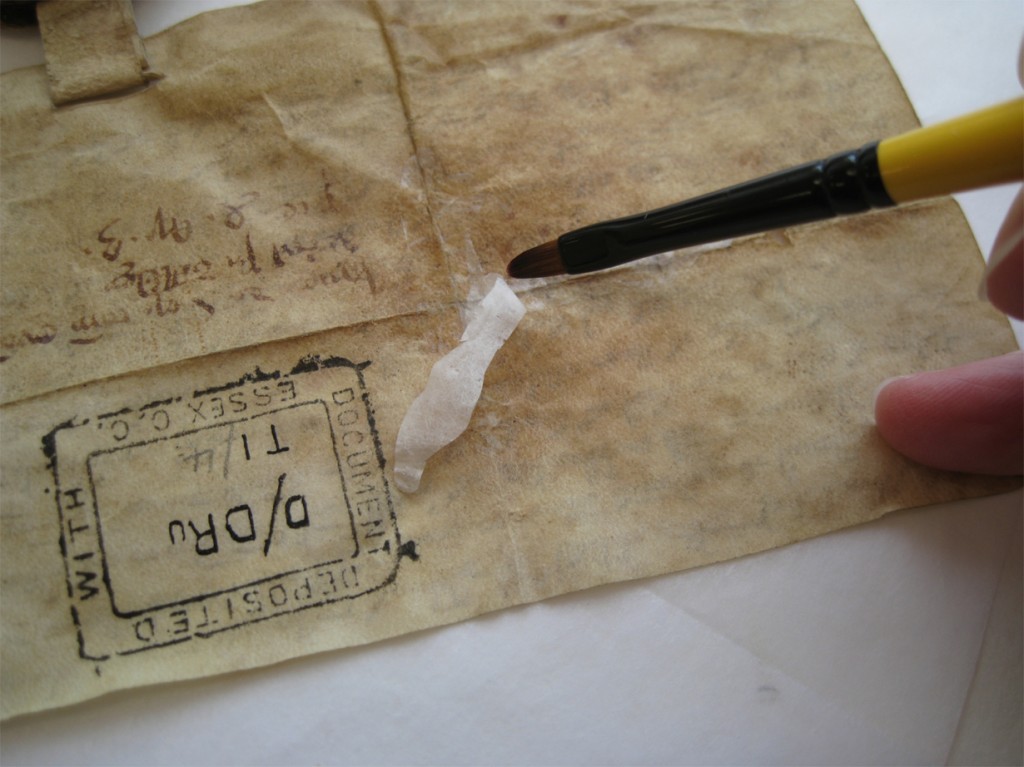

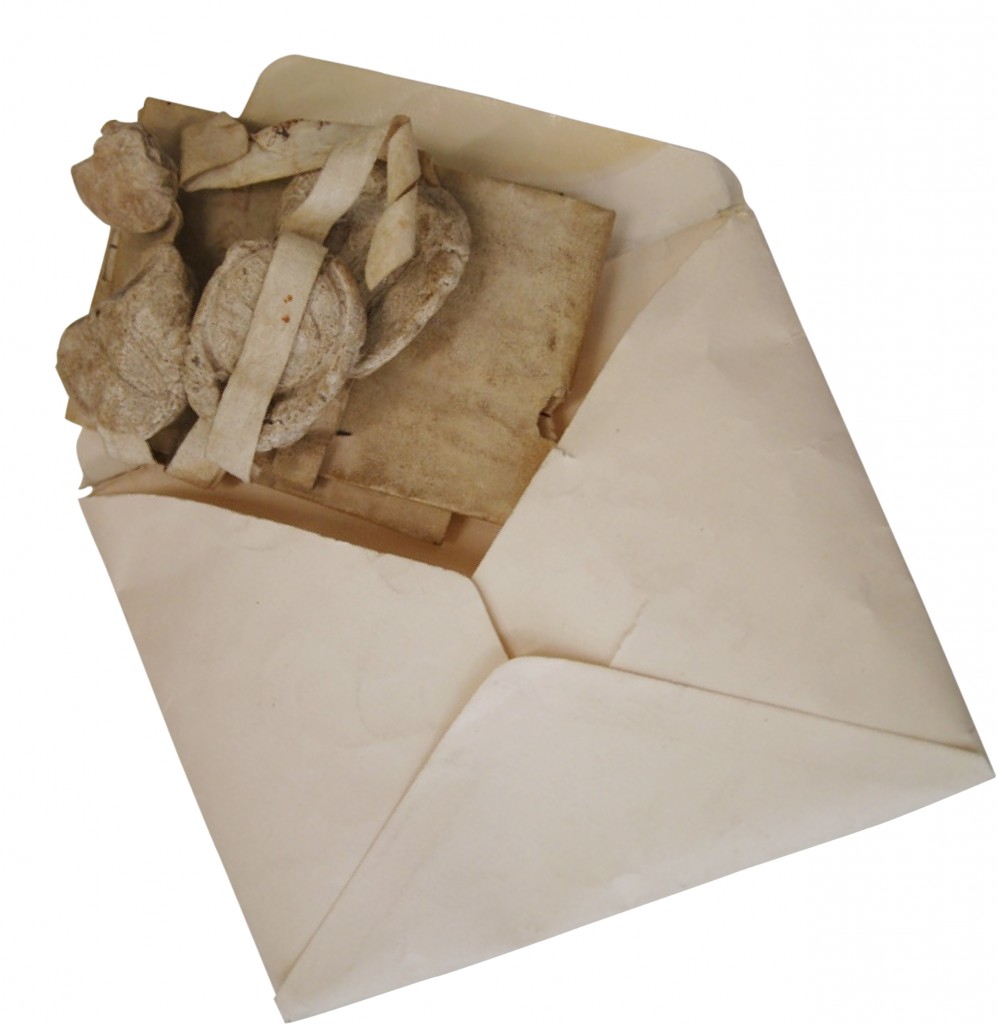

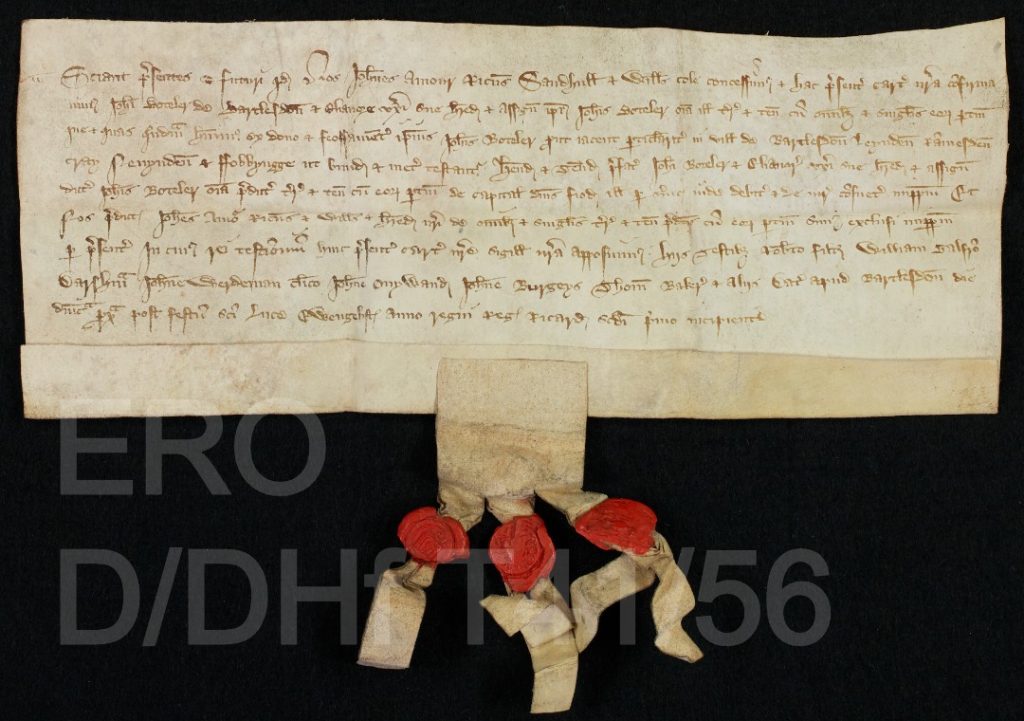

Amongst the documents on display at the launch event– mainly manorial court rolls – was this rather inconspicuous property deed dating from four years before the revolt.

In the list of witnesses in the otherwise unremarkable grant of lands and tenements in Laindon, Ramsden Crays, Nevendon and Fobbing is one Thomas Baker. This is very likely the Thomas Baker who was named by the contemporary chronicler Henry Knighton as the ‘first mover’ of the rebellion.

In several inquests after the rising Baker was accused of having been present at Brentwood on 30 May 1381, when a royal commission enquiring into non-payment of the third poll tax was put to rout. Afterwards he ordered messengers to proclaim the uprising in south-Essex and probably beyond the Thames in Kent.

He was also charged with taking part in the attack on Cressing Temple and Coggeshall. He was found guilty as charged and drawn and hanged in Chelmsford on 4 July 1381.

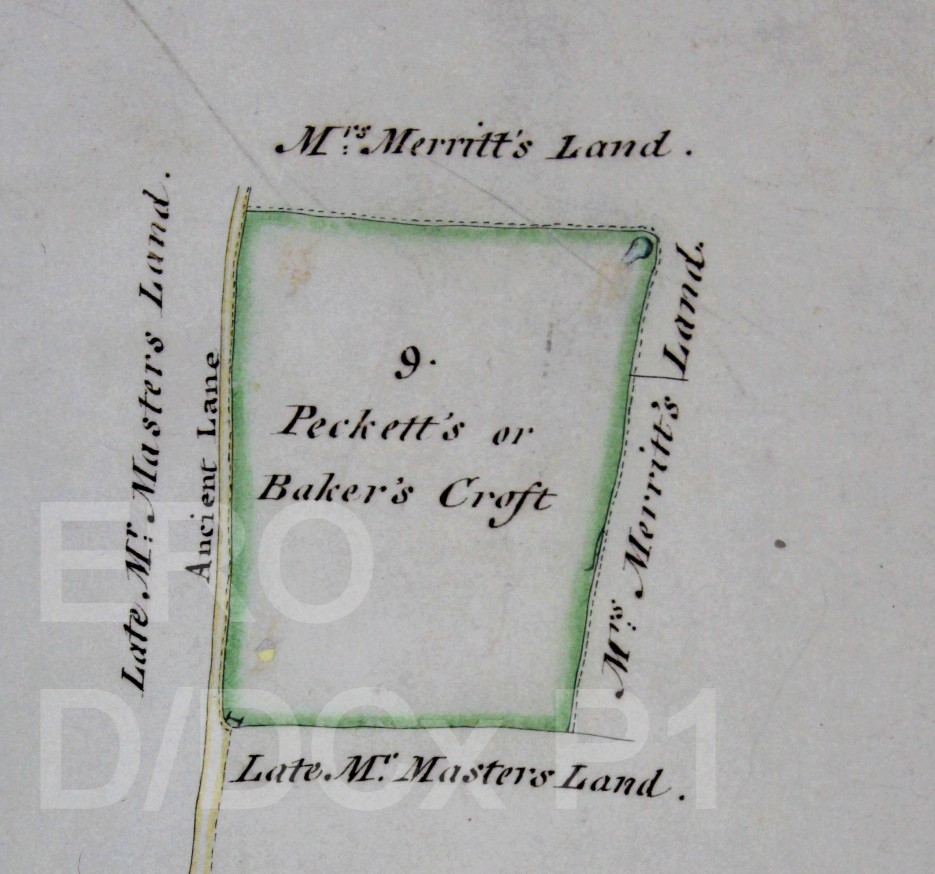

It is known from an escheator inquisition taken eight years after the rising that, at the time of his death, Thomas held of the abbot of Waltham Holy Cross a croft called ‘Bakerescroft’ containing 6 acres of land in Fobbing as well as a messuage with garden of Joan de Bohun, countess of Hereford, and lady of the manor of Fobbing.

Map of estate of Thomas Drew in Fobbing and Corringham, 1781 (D/DCx P1)

This map, dated four hundred years after the Peasants’ Revolt, shows Bakers Croft in Fobbing: a smallholding of more than 6 acres of land. It has been identified as possibly being the land of the rebel Thomas Baker.

Yet, nothing is known about his life up to 1381.

The manorial documents of Fobbing in the second half of the 14th century are lost. This is where this snippet of information from the deed fits in nicely. Witnesses to medieval deeds were trustworthy local men of some standing. We can therefore infer that Thomas Baker was prominent in his area before he assumed a leading role in the repulsion of the tax commission.

A final twist is revealed by the presence of two other witness names. One, Geoffrey Darsham, or Dersham, who was the Earl of Oxford’s steward in south-east Essex, had his manor house of Barnhall in Downham destroyed and livestock stolen, and John Onywand, another of the deed’s witnesses, was a member of the jury presenting this allegation in 1381.

It is intriguing that three of the six people coming together in October 1377 to witness a land transaction found themselves on different sides of the divide only four years later: a rebel, a victim of the rebels, and a juror.

For more about the Peasants’ Revolt visit http://www.1381.online/