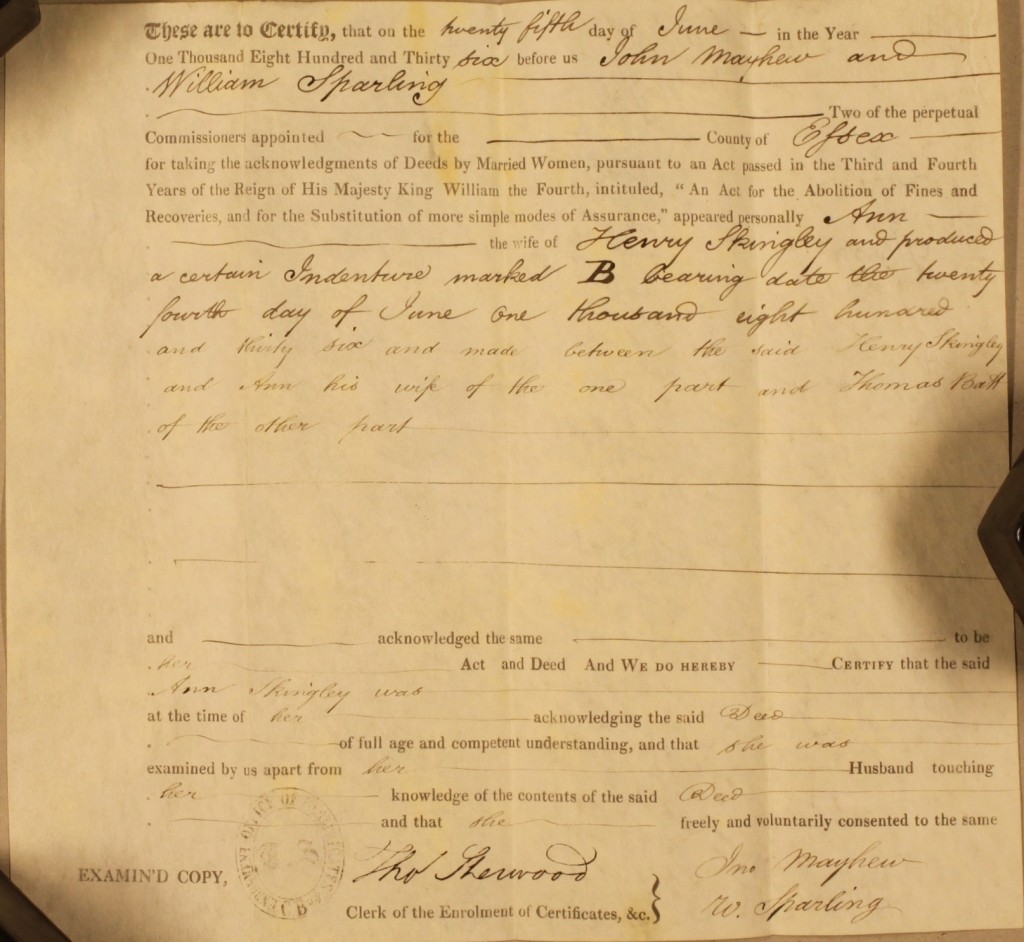

Historic buildings specialist and ERO user Edmund Harris writes for us on a hidden gem of Victoriana in the village of Creeksea. This post draws on the Chancellor collection, made up of some 10,000 building plans from the office of noted Victorian architect Fred Chancellor. We are currently two years into a long-term project to clean, repackage and catalogue every one of these plans; find out more here.

Creeksea (sometimes called Cricksea) is a tiny village now virtually on the western outskirts of Burnham-on-Crouch, with long, tranquil views to the south over the gentle landscape of the Crouch estuary.

Existing literature on the county is mostly likely to send a lover of antiquities there to look at Creeksea Place, a fragment of a once much larger Elizabethan house, possibly also Creeksea Hall and a half-timbered cottage.

But anyone other than the most steadfastly curious of enthusiasts for Victoriana might well be put off investigating the parish church of All Saints by mentions of a complete rebuild in 1878; Essex has several nationally important and much celebrated 19th century churches but this is not generally recognised as one of them. That would, however, be a great shame, as All Saints is actually a most remarkable building that handsomely repays closer examination.

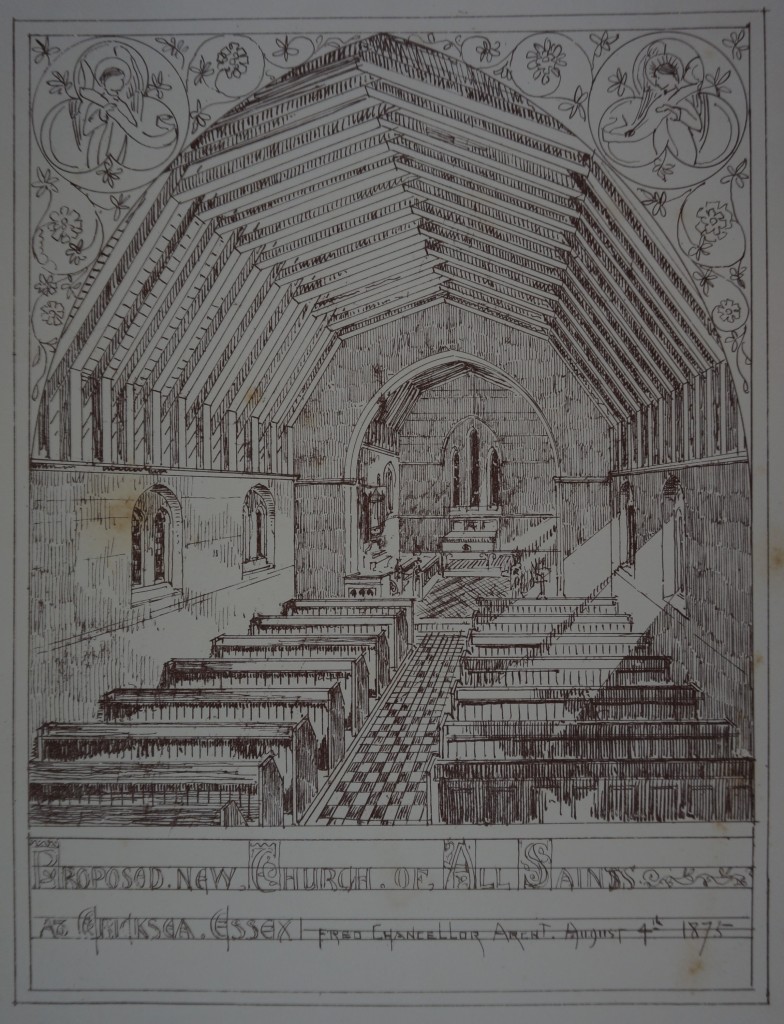

It is indeed almost entirely a rebuild by Frederic Chancellor, but the evolution of his design is far more complicated than one might expect. A splendid set of several dozen drawings in the ERO details an intriguing design process.

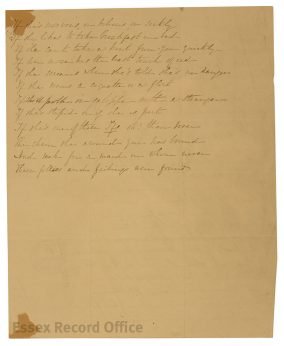

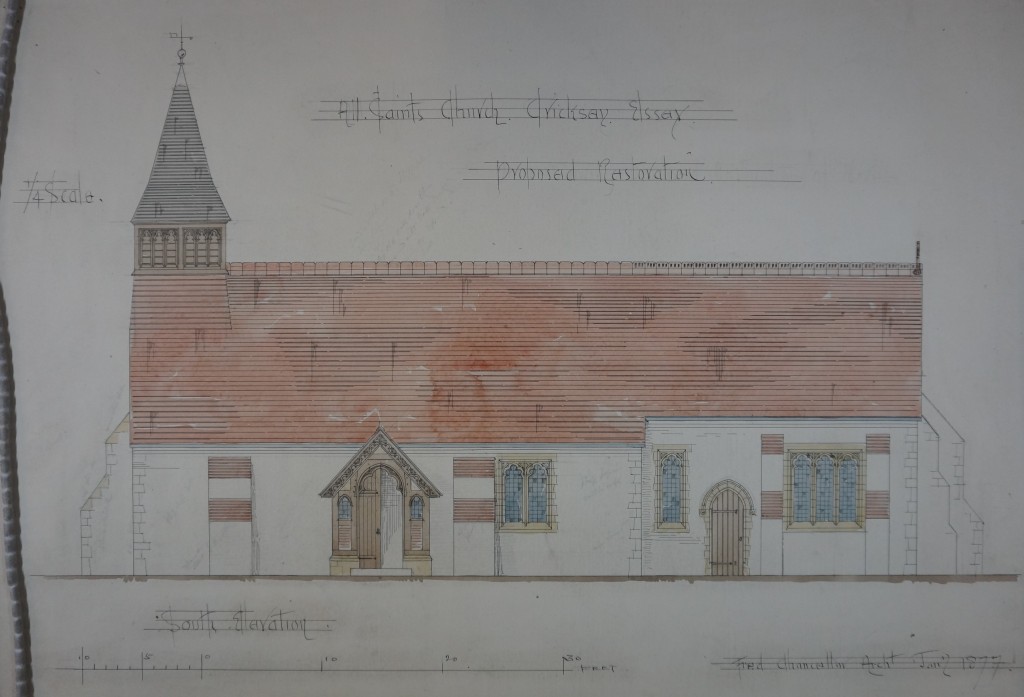

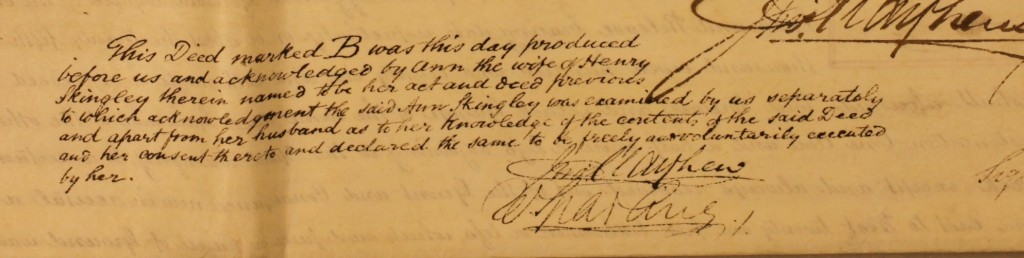

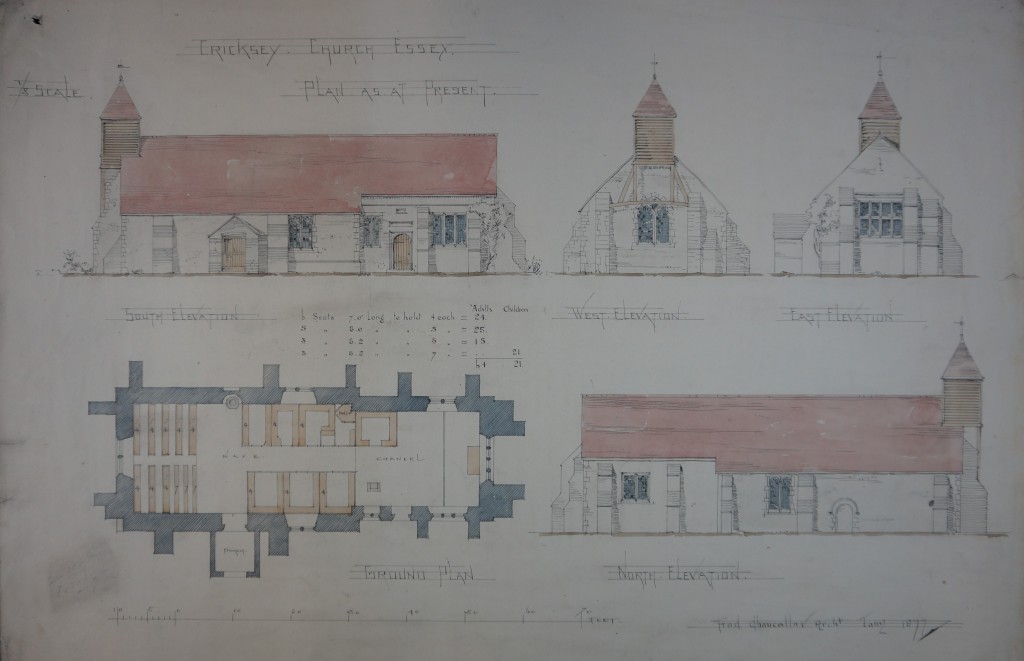

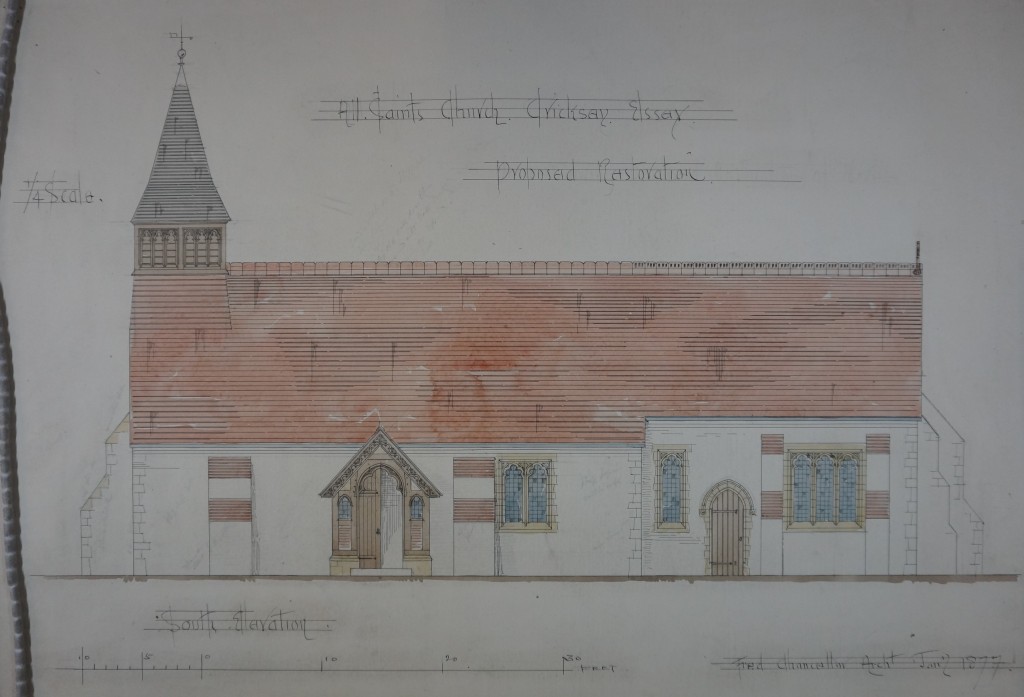

We know what the predecessor of the present church looked like thanks to a plan and elevations from Chancellor’s office dated January 1877, which show a simple, modest two-cell building, clearly much patched and mended in a rather ad hoc fashion over the years (witness the trusses bridging the buttresses to the west wall on which the bellcote is supported), evidently seated internally with box pews.

The old church – click for larger version

Today we should say that this gave it charm of as great a value as its antiquity – the round-arched north door suggests Norman origins – but to the Victorian mind such a building would have appeared so badly degraded as to be of minimal interest. It would have suggested a Church of England in decline and looked wanting in pride and propriety. The building would have been unsuited to Victorian liturgical practice and features such as the oblong, probably Elizabethan east window would probably have been viewed as downright inappropriate for a religious building.

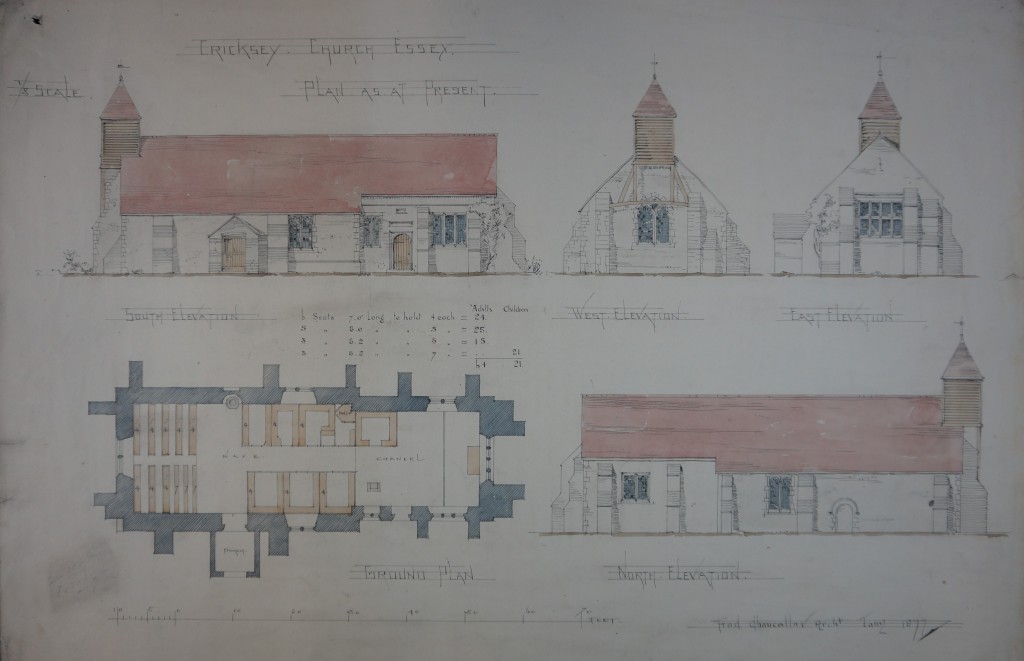

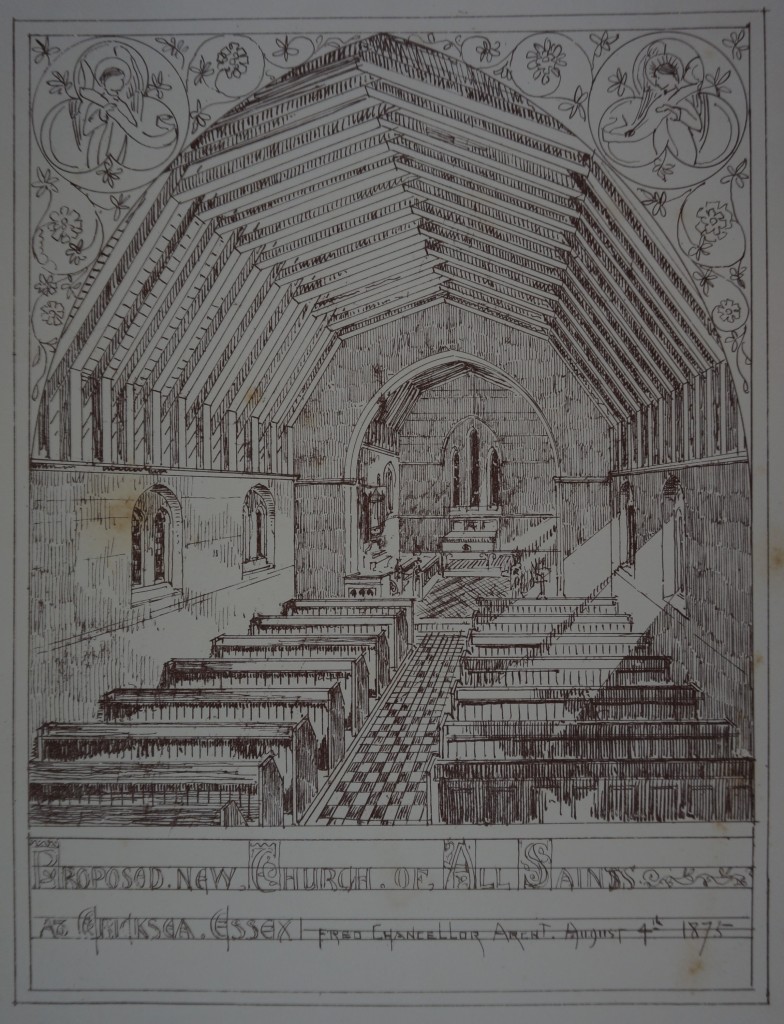

But Chancellor’s involvement with All Saints in fact seems to have begun well over a year previously. An artist’s impression dated 4th August 1875, shows the interior of what is called ‘a proposed new church’ in a very plain lancet style – decent, but clearly the work of an architect confined by a limited budget. It looks like it might have been intended for publication and may have been no more than a concept sketch.

An artist’s impression dated 4th August 1875, showing the interior of ‘a proposed new church’

Only one drawing on file gives any more information about it: a view of the south elevation (executed in pencil rather than pen and wash) shows something that is clearly a precursor of what was eventually built but far plainer. Features such as the paired lancets to the side wall of the nave give it very clear affinities with another, this time undated proposal.

Unlike the August 1875 scheme it was aimed at rebuilding just the nave, but this time was pursued as far as a set of contract-standard drawings. Externally the rebuilt nave appears rather forbidding and Chancellor initially struggled to make a virtue of the building’s simplicity. It looks as though it was probably meant to be rendered with only the stone quoins left visible. While instantly recognisable as a product of the High Victorian movement, the building lacks any sort of sense of local character. Which of these schemes came first is a mystery. Perhaps initial plans for a complete rebuild had to be scaled back to replacing just the nave when it became apparent the cost would be excessive, but that is conjecture.

Undated proposal to rebuild the nave – south elevation

What happened next is not clear, but it is a reasonable bet that finances outstripped by the parish’s ambitions put a check on progress since in December 1876 and January 1877 designs emerged from Chancellor’s office for a restoration of the medieval building. ‘Restoration’ was, as so often the case at this time, something of a euphemism. In fact it was nothing less than a comprehensive remodelling since the building was to be refenestrated throughout, the bellcote and roof replaced, the interior refurnished, a new porch added on the south side and a vestry built onto the north wall of the chancel. Probably the pattern of events that led to this was nothing more than an accident, but if so it was a happy one since it seems to have forced Chancellor to take a closer look at the existing building and its character. Picturesque touches such as the partly timbered chancel and vestry gables now appear and generally there is greater care and finesse in the detailing than in the first two designs.

Plans for restoration scheme, 1876/6 – south elevation

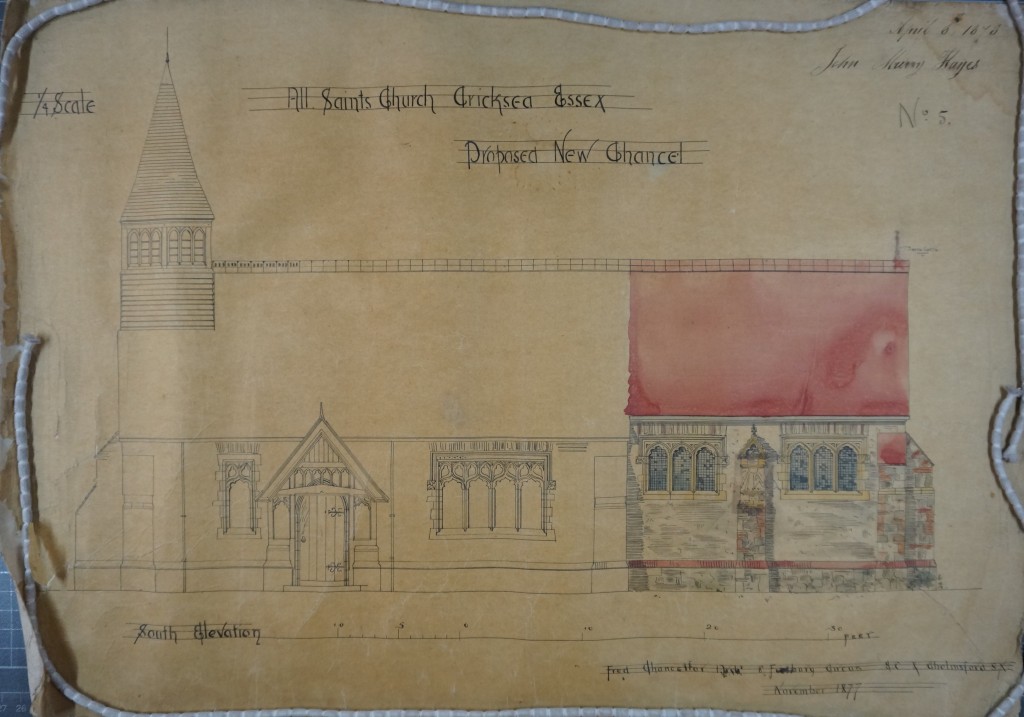

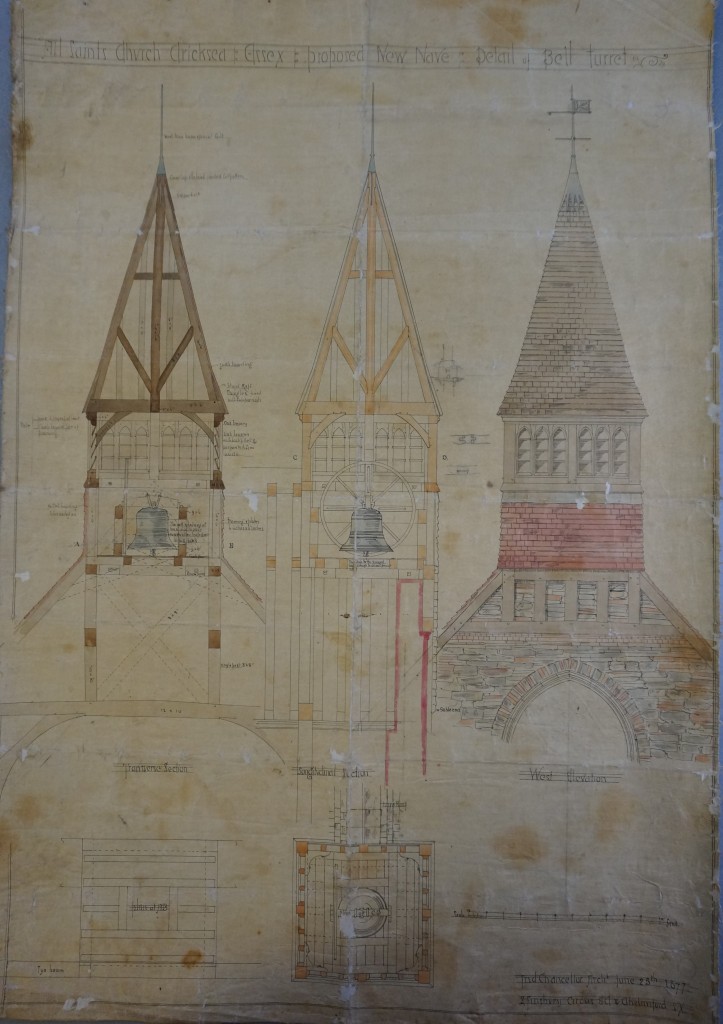

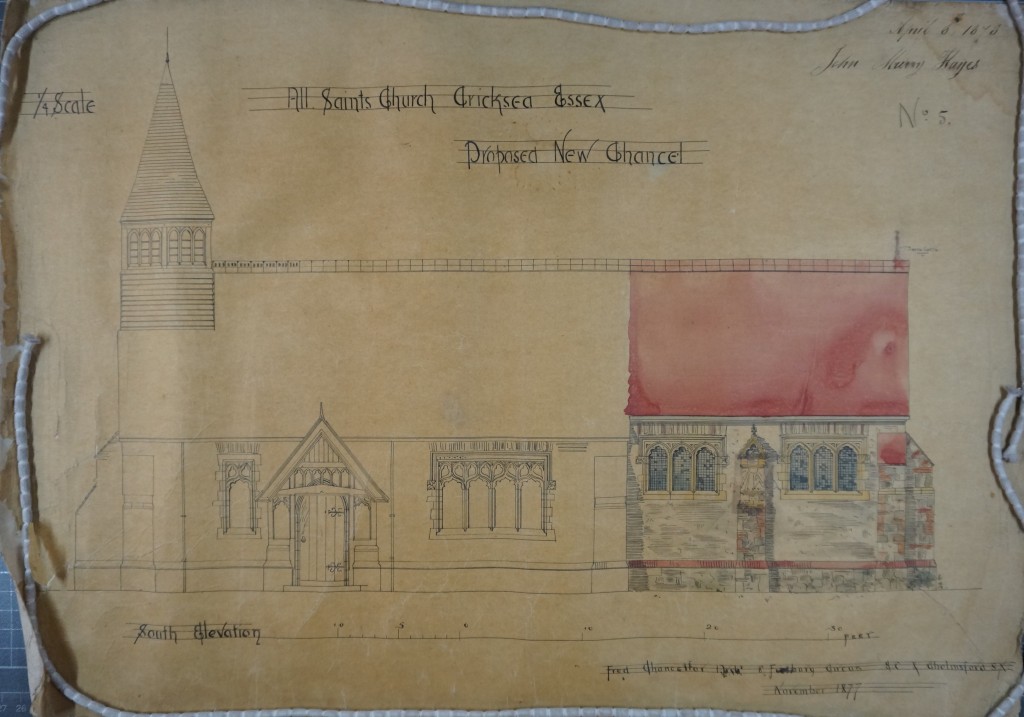

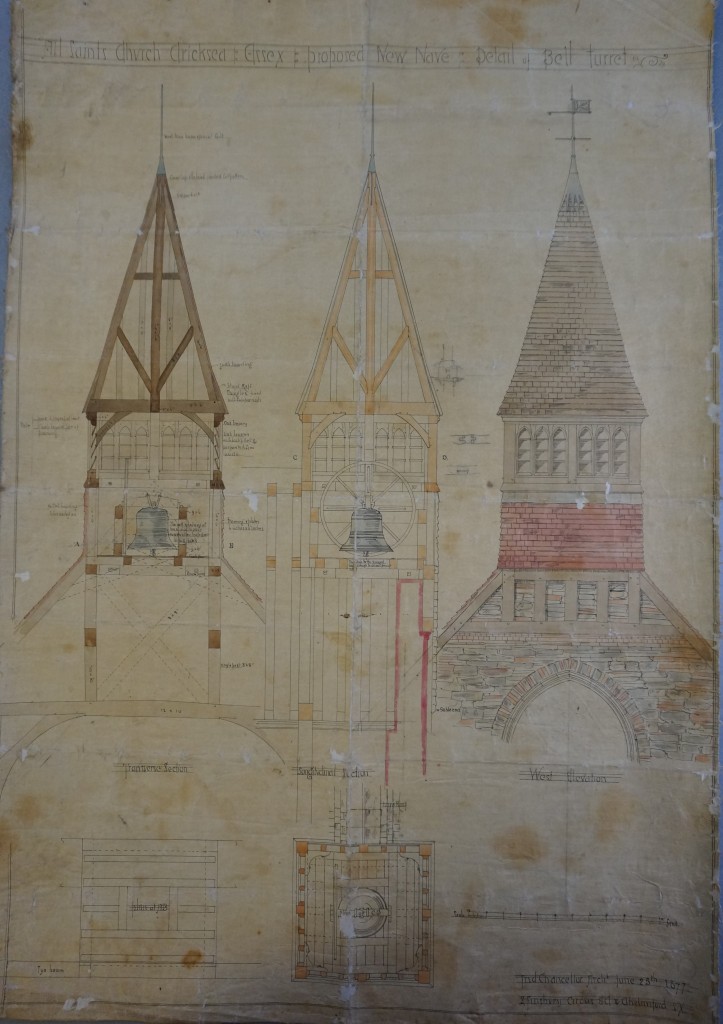

Perhaps the condition of the existing fabric turned out to be too poor to withstand such substantial new additions. Or perhaps the cost was only marginally less than a complete rebuild and the parish, taking a long-term view, felt that on balance an entirely new building represented much better value for money. Perhaps even a generous sponsor appeared. Without further research neither hypothesis can be corroborated, but the restoration project was not entertained for long and between February and June 1877 Chancellor produced drawings for the nave that was eventually built. Like the earlier scheme, it shows the medieval chancel left intact, but that seems to have been a temporary expedient – probably only done so that divine service could continue while the work was carried out – since a further set of drawings dated November 1877 and March 1878 depicts the existing structure that superseded it, completing Chancellor’s new church. Notably, not just the pen and wash contract drawings survive at the ERO, but also detailed working drawings for features such as the bellcote and porch.

Proposed new chancel, 1877 scheme – south elevation

Detail of the bell turret from 1877 scheme

So much for the chronology of the design process. Beautiful though these fine examples of Victorian architectural draughtsmanship are, the building that eventually resulted from all these false starts is even lovelier. The contrast with the 1875 initial version of the scheme is striking. The dour lancet style has given way to an ornate, almost fruity Perpendicular Gothic. The lush foliate carving – something shown in a series on file of delicate pencil drawings – that adorns the screen dividing the vestry from the chancel, the large, four-light window on the south side of the nave and the panelled pulpit would not disgrace a far grander building.

But the really memorable thing about the church is the wonderful treatment of the walls. Faced with a lack of good, locally available stone, the builders of Essex’s medieval churches had to press into surface whatever came to hand, from pudding stone to flint to brick from the ruins of Roman Colchester, giving the exteriors of many of them a charming, variegated, patchwork effect. No doubt Chancellor was keen to offset the value of material recovered from the old building against the cost of the construction of its replacement (a fragment of a Norman arch with typical chevron decoration can be seen built into one wall) but he made a real virtue of his economy. This sensitivity to local materials and traditions is remarkable for its date. It would become a major article of faith for leading figures in the Arts and Crafts movement, but not for another decade or so. And while some of those architects were content to let their builders produce the exuberant effects they desired, the drawings show that delightful features such as the striped window heads were Chancellor’s own inspiration.

The long wait, the vagaries of the design process and the choice of an architect with local roots paid off. Frederic Chancellor did right by the parishioners of Creeksea.