Archivist Chris Lambert shares his selection for July’s Document of the Month

Recent tragic events have underlined the public desire to help those caught up in catastrophe. In the 17th century, when state and society commonly saw themselves as a single Christian entity, the characteristic expression of that desire was the brief.

England had already invented social care. An Act of 1601 had created the parish poor rate, distributed in goods or money to the deserving poor. There were also charities providing food, fuel and housing. These initiatives, however, dealt only with ordinary needs. Catastrophic events involved another process, in which the state mobilized voluntary giving from society at large.

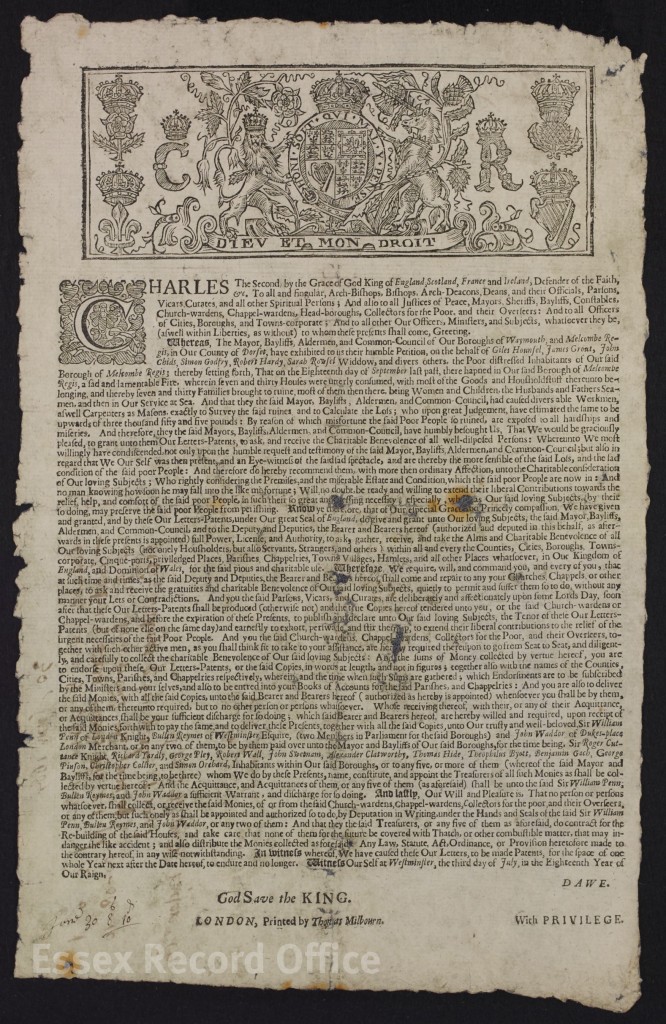

The Crown, on petition, would issue letters patent allowing the gathering of contributions from ‘all well-disposed persons’. Individuals named in the grant would then employ collectors to carry the appeal around the country. The original handwritten letters patent, issued under the Great Seal, tend not to survive, but in a way they hardly mattered. The process really depended on the use of printing technology to make copies – ‘briefs’ – for distribution. The printed copies became so familiar that their title of ‘brief’ was applied to the whole process.

This particular brief (D/P 152/7/2), from the parish records of Theydon Garnon, was issued in 1666 in aid of Melcombe Regis (Weymouth) in Dorset. In September 1665 the town had suffered a ‘sad and lamentable fire, wherein seven and thirty houses were utterly consumed’. Their occupants had been ‘brought to ruine’, the total loss being estimated at £3,055. Such fires were not uncommon. Much less usual is the note, in King Charles’s name, that ‘We Our Self was then present and an eye-witness of the said sad spectacle, and are thereby the more sensible of the said loss’. The King had indeed been in the West Country during that summer of 1665, taking refuge from the Great Plague in London.

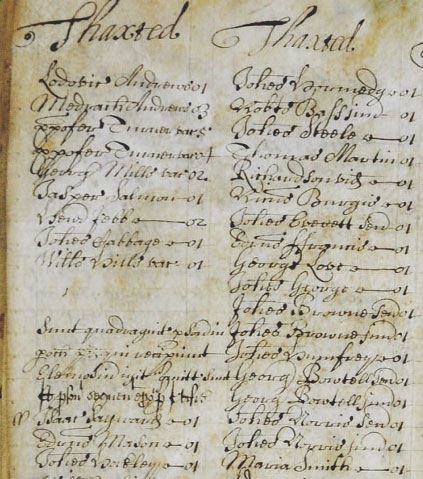

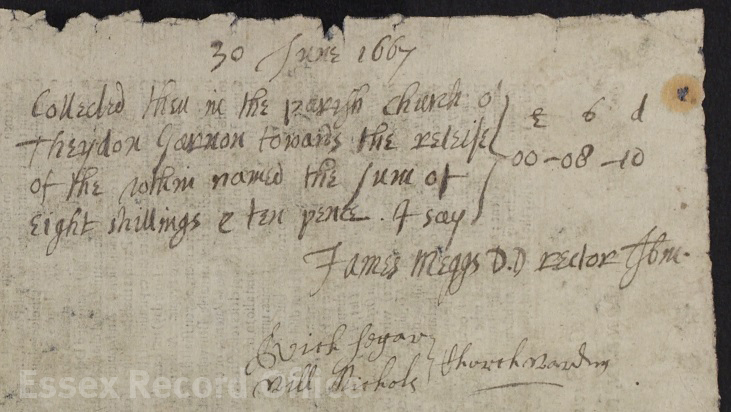

Some briefs allowed for house-to-house collections, but charity being above all a Christian duty, the normal mechanism for collecting the money was the parish, then both a religious institution and the foundation of local society. The clergy ‘published’ the brief at a Sunday service and exhorted their parishioners to contribute, the amounts raised being written on the back of the brief. When this example reached Theydon Garnon in the summer of 1667 – almost a year after it was issued and almost two years after the fire – that one parish collected 8 shillings and 10 pence (for comparison, a few months earlier they had raised £27 5s. for the Great Fire of London). In this case they were to deliver the money back, via the appointed persons, to the authorities in Weymouth. They in turn were to ‘contract for the re-building of the said houses’, taking care ‘that none of them for the future be covered with thatch, or other combustible matter’.

Note on the back of the brief recording how much was collected: ‘Collected then in the parish church of Theydon Garnon towards the releife of the w[i]thin named the sum of eight shillings & ten pence. I say James Meggs DD Rector’

The system had obvious defects. Slow, cumbersome and costly at best, it was also open to fraud. Security measures such as expiry dates (one year, in this case) offered little real protection. The Essex Quarter Sessions records show evidence of prosecutions – in 1647 for collections on a wholly fraudulent brief (Q/SR 333/105, Q/SBc 2/35), and in 1653 for collections on what may have been a genuine brief by someone apparently unconnected with the parties concerned (Q/SBa 2/82). Eventually a reforming Act in 1705 tried to clean up the system, providing an elaborate system of registration, with all briefs now being printed by the Queen’s Printer. A handful of Essex parishes still have the registers of collections that the Act required.

The earliest collections so far traced in the ERO’s holdings were in the 1570s, for the reinstatement of Collington (Colyton) Haven, a harbour in Devon. For that purpose in 1575 the little Essex parish of Heydon raised 6s.8d.; Canewdon collected 1s.8d. in 1576/7, and then another 1s. two years later. Briefs continued to be issued even under the Commonwealth, but seem to have been at their peak under the restored monarchy of the late 17th century. Over time, however, fire and flood became matters mainly for the insurance industry, and the objectives of briefs were limited largely to church building.

Briefs effectively came to an end in 1828, when responsibility for churches was transferred to the Incorporated Church Building Society. The need for large-scale relief funds eventually found expression in more secular ways. From the late 19th century many such efforts were organized through the Lord Mayor of London. The Titanic Disaster Fund of 1912 – later the National Disasters Relief Fund – was one of these. Mass media and then social media opened new possibilities, and online donation sites operate very differently from the state-sponsored briefs of old, but they draw on the same urge to help strangers in need.

The document will be on display in the ERO Searchroom throughout July 2017.