Following our recent post on what a manor was, Archivist Katharine Schofield takes a more detailed look at manorial court rolls. You can find out more about manorial records and how you can use them in your own research at Essex through the ages: tracing the past using manorial records on Saturday 12 July 2014.

The majority of manorial records in the Essex Record Office are the records of the manorial courts, which are among the most important sources for medieval social and economic history.

Their greatest importance is in recording the lives of the ‘ordinary people’ of the county; in the years before parish registers began to be kept in 1538, these might be the only records in which a relatively ordinary person might appear. Some of the Essex manorial rolls also contain evidence of events of national significance, such as the Black Death of 1348-1349 and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

The manor courts dealt with everything from maintaining hedges and ditches to keeping the peace when disagreements (and sometimes violence) broke out amongst the manor’s tenants.

The court was presided over by the lord of the manor, or more usually by his steward. The records were kept in Latin until 1733, but if you don’t read Latin don’t let that put you off; the later material is in English and these records are stuffed full with fascinating details of daily life in the past.

The earliest records are rolls made up of membranes of parchment stitched together at the top. Although these records are cumbersome and unwieldy to use today, this was the quickest and easiest way to maintain a working accessible record

There were two types of manorial court, the court baron and the court leet, although the earlier rolls do not distinguish between the two. Broadly speaking, the court baron dealt with matters pertaining to the administration of the manor, and the court leet handled minor criminal offences.

The court baron

The court baron handled the administration of the manor, including customs (such as the use of common land for pasture, and maintaining buildings, paths and hedges), settling disputes between tenants, enforcing the rights of the lord and any infringements, and on occasion requiring the lord to fulfil his obligations towards the tenants.

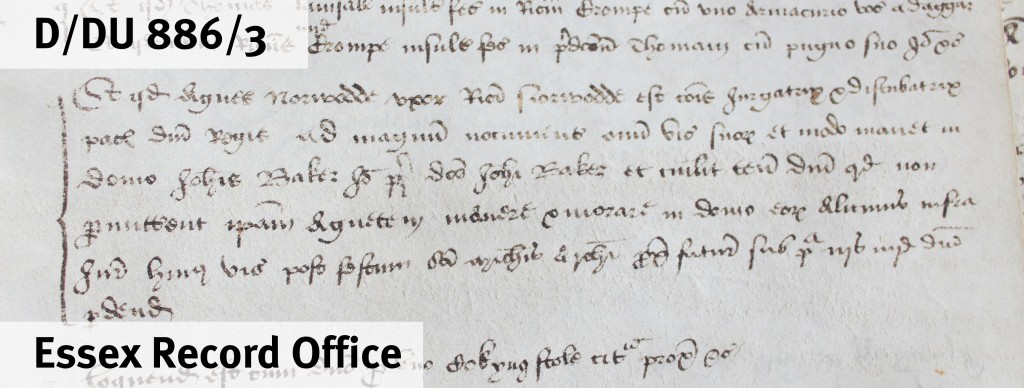

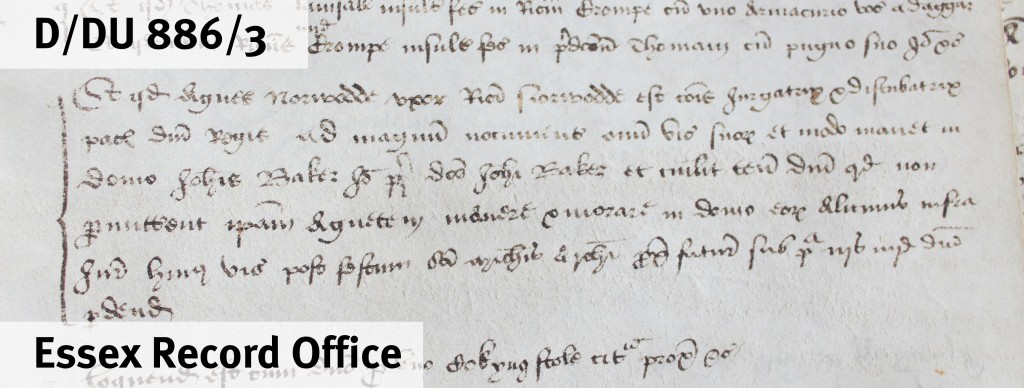

The court rolls record fines levied on tenants for breaking the rules of the manor, such as trespass against the rights of the lord or other tenants, or failing to keep roads, paths and ditches clear. In Writtle in 1452 for example, seven animals of John Croucheman strayed on to the land of another tenant and ate two haycocks (a small cone-shaped pile of hay left in the field until dry enough to carry to the rick or barn), and in 1477 two tenants of the manor of Great Burstead were fined for leaving dung in the main street of Billericay in front of the chapel. There were also cases where tenants were bound to keep the peace towards each other and occasions where women were presented as a ‘common scold’. At High Roding in 1525 Agnes Norwood was presented as a scold and disturber of the peace and no tenant was to allow her to live in their house on pain of a fine of 3s.4d (D/DU 886/3).

Extract from court roll of High Roding, 1525 (D/DU 886/3), in which Agnes Norwood (you can read her name in the third and fourth words on the first full line shown) was denounced as a scold and disturber of the peace. She had been living in the house of John Baker – you can make out his name in the third full line shown.

The rolls also record the customary fines tenants owed. These included ‘chevage’, the right to live outside the manor. In 1356, for example, a tenant of the manor of Bulphan paid 6d. for a licence.

The court baron was also responsible for the appointment of various officers, including the reeve who would collect rents and ensure that the tenants fulfilled their obligations, and the haywards and woodwards who were responsible for the maintenance of hedges, fences and woods. By the 16th century this business had become much less important.

The deaths of tenants and admissions of new tenants to land were also recorded by the court baron. The lord was entitled to the payment of a ‘heriot’ (usually the best beast) on the death of a tenant and an entry fine by the incoming tenant. Tenants of manors were described as ‘copyholders’ as they held land by copy of the court roll. Copyhold land could be bought and sold and left by will and many hundreds of copyhold deeds survive in the Essex Record Office. From the 16th to the 20th century most of the business of manorial courts related to the recording of admissions and surrenders of copyhold land. With the decline and eventual cessation of this type of landholding in 1922, the business of the courts baron ceased.

The court leet

The court leet was the lowest court of law enforcement and dealt with minor offences, such as nuisances, affray or assault, selling faulty goods, using false weights and measures, playing unlawful games, keeping disorderly alehouses, disturbing the peace and keeping inmates and vagabonds. The court was also responsible for the election of the constable.

The court leet was also where the lord of a manor would hold something called ‘the view of frankpledge’. Many, but not all, manorial lords had the right to do this. This was a practice with Anglo-Saxon origins. All able-bodied men in a manor were grouped in tithings (roughly 10 men). All the men of the tithing were bound in mutual assurance to observe and uphold the law – if a member of a tithing broke the law then the rest were obliged to report the crime and deliver the culprit to the constable. Failure to do this would result in everybody in the tithing being fined. If the lord of the manor had the right to hold the view of frankpledge then the chief man of each tithing (called variously tithing men, headboroughs, decenners or capital pledges) would report to the court leet to represent his tithing.

Tenants could also be fined by the court for failing to obey the law. Offences included keeping unlicensed alehouses, not practising archery (all men were required by law to practise their archery so their skills could be drawn upon in times of war), and playing unlawful games; in 1564 and 1565 14 men in Ingatestone were each fined 4d. or 8d. for bowling.

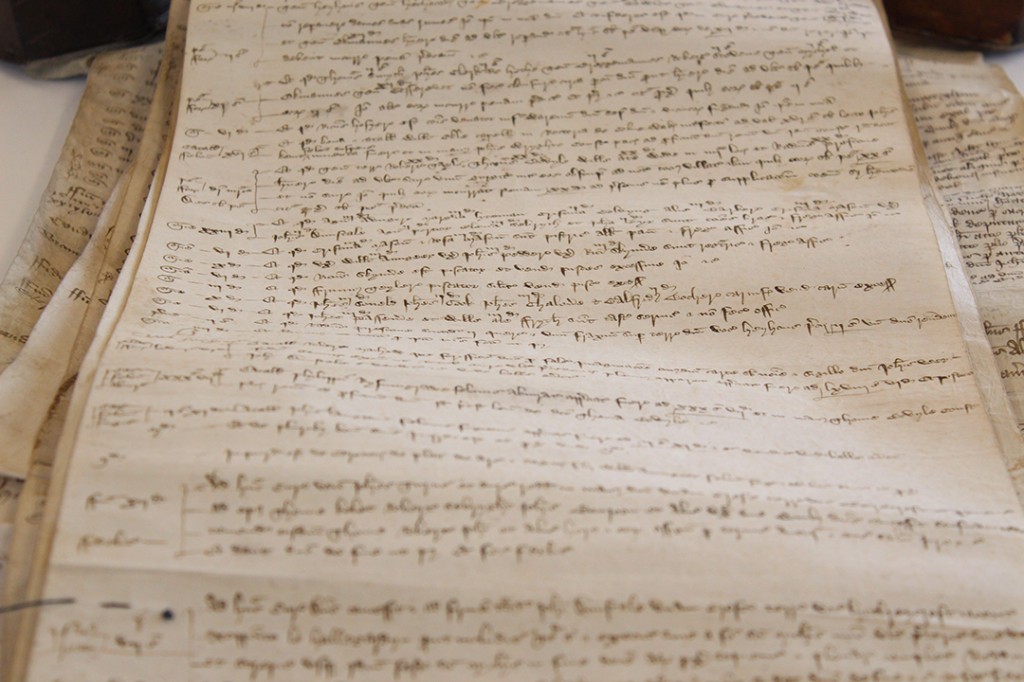

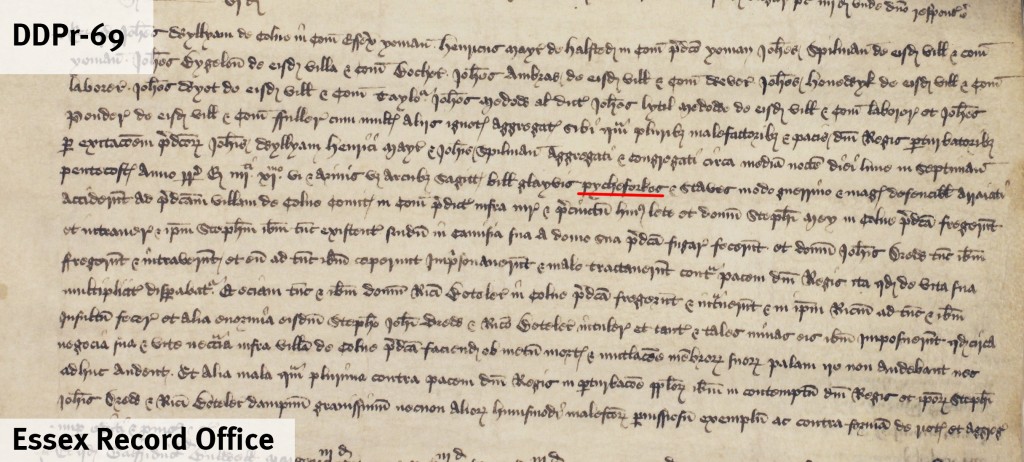

There were also more serious crimes, including cases of assault. In 1467 Thomas Hurst of West Hanningfield was fined for breaking into his neighbour’s house by force, taking his goods and claiming him to be outlaw. In 1472 in Earls Colne a mob of gathered with bows, arrows, pitchforks and other weapons and broke into the houses of three tenants, dragging one out in his shirt, and beating them severely. You can read a full translation of the passage here.

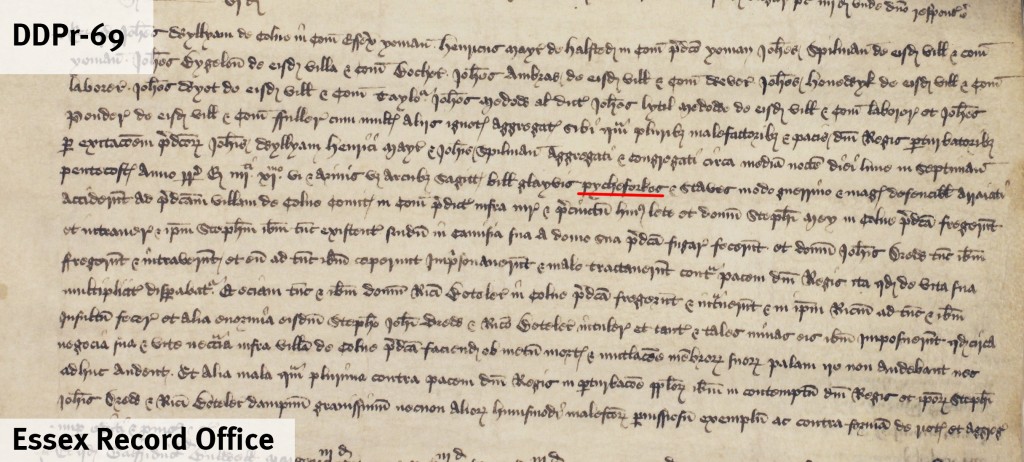

Extract from D/DPr 69, a court roll from Earls Colne, which describes a serious assault. The court seems to have given up trying to translate ‘pitchforks’ into Latin, and written it as ‘pycheforkes’ (underlined in red).

During the 16th century most of the legal cases were being dealt with by Quarter Sessions and by the 17th century the court leet had no significance and rarely, if ever, met.

Whether you are interested in using manorial records in your own research, or just want to enjoy hearing experts talk about them, join us for Essex through the ages: tracing the past using manorial records on Saturday 12 July 2014 to find out how you can discover centuries of Essex life using these fascinating documents. There are more details, including how to book, here.