Wills can tell us all sorts of things about the lives of people in the past, and are a brilliant resource for genealogists and social and economic historians alike.

As we have mentioned before, our collections include some 70,000 original wills made by people in Essex between 1400 and 1858. These wills have all been catalogued and digitised, and can be searched for by name and viewed on our online subscription service Essex Ancestors.

We have now begun work on an additional set of records which can help to fill in any gaps in our series of original wills, which will ultimately result in about 10,000 more wills being added to Essex Ancestors.

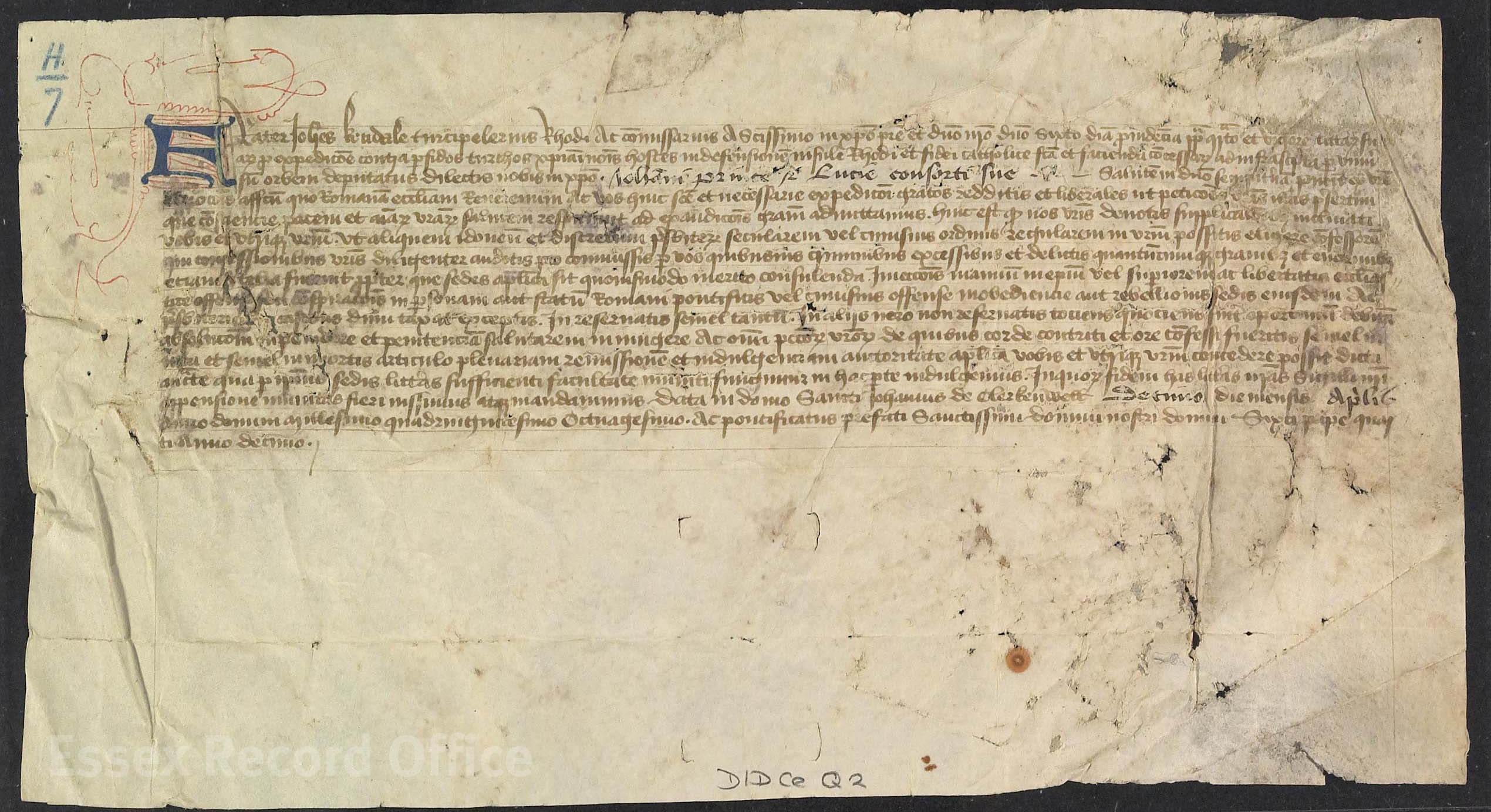

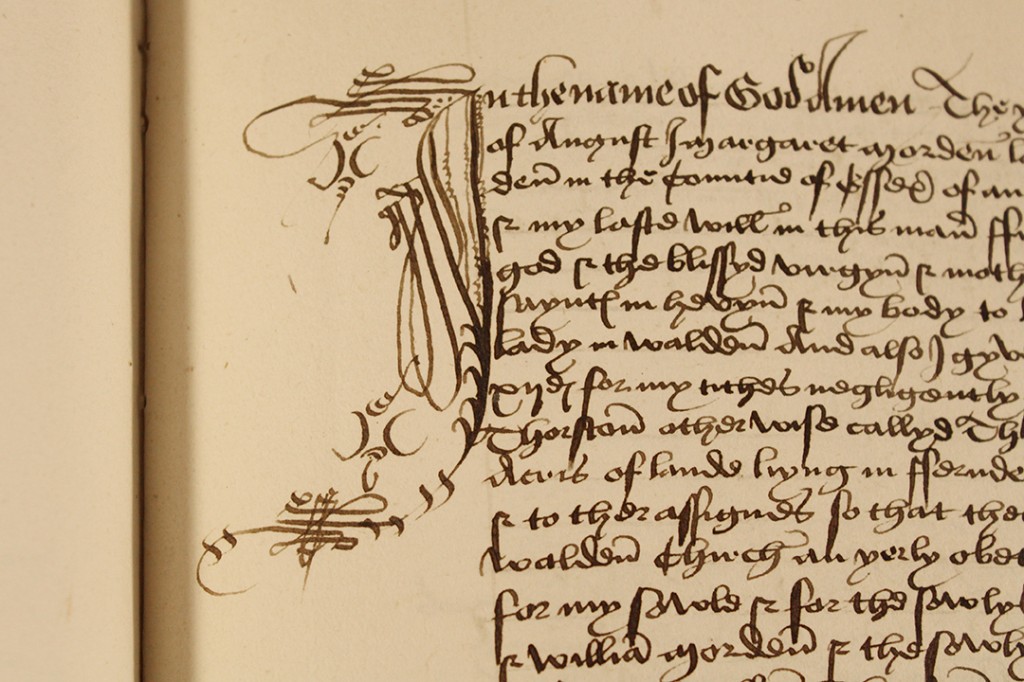

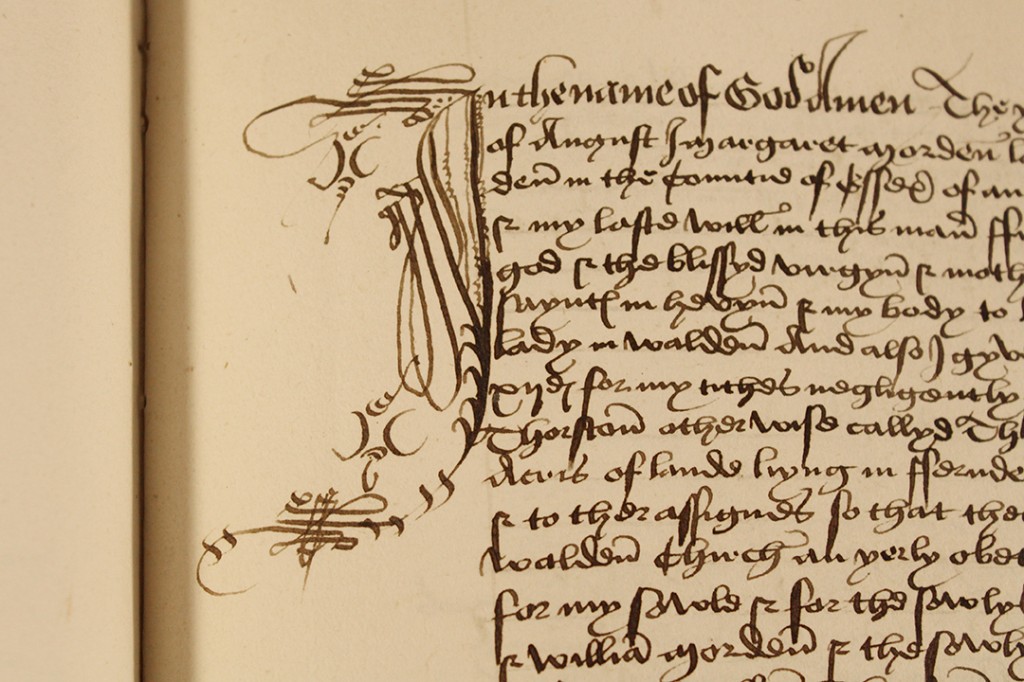

A decorative initial ‘I’ from a book of registered wills dating from 1500-1515 (D/ACR 1)

Before 1858 when somebody died leaving a will, their executor would take the original will to the relevant court so that probate could be granted. The original wills would be kept by the court and filed; it is these wills proved in the ecclesiastical courts in Essex which have been digitised and are available via Essex Ancestors.

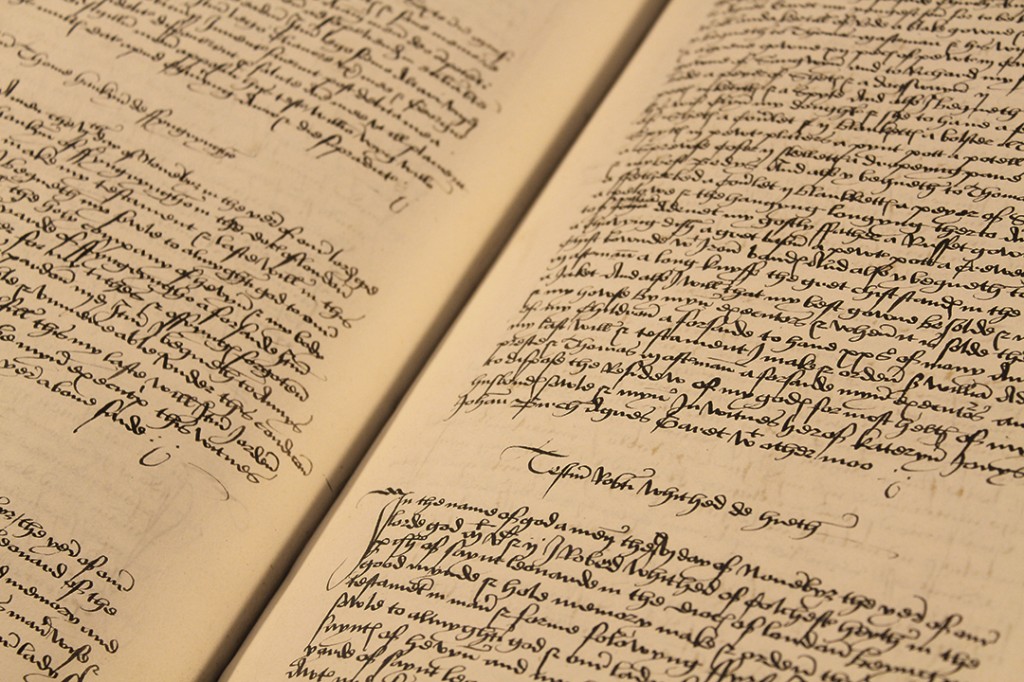

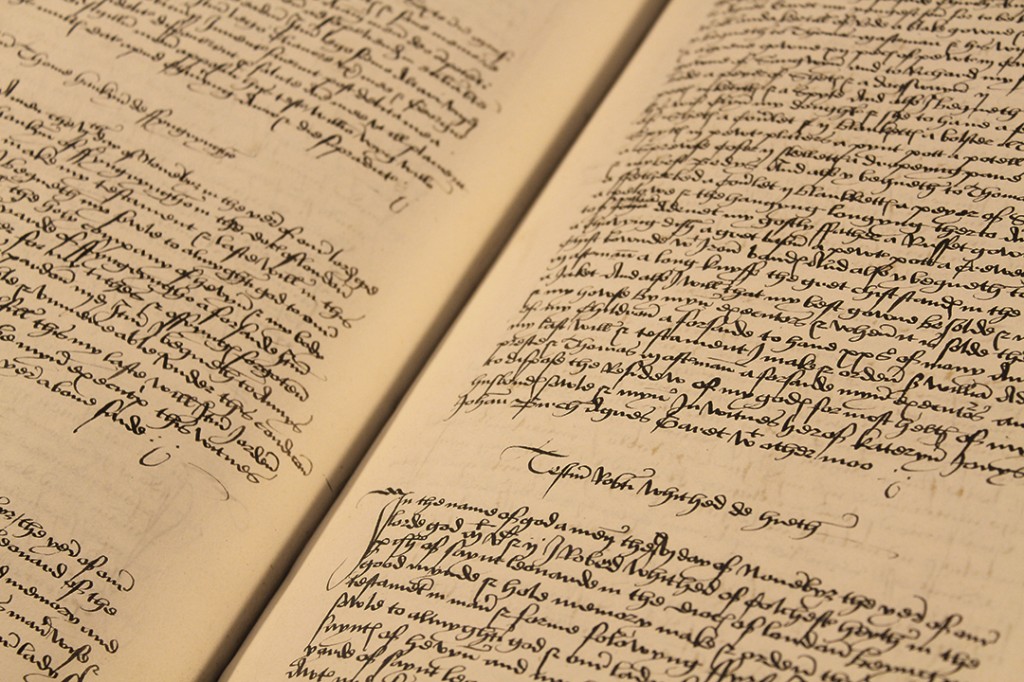

Clerks at the courts would also usually write out a copy of the will into large volumes called will registers (references beginning D/ABR, D/ACR, D/AER and D/AMR). There are approximately thirty 16th and 17th century registers for the courts in Essex where there are no original wills surviving.

The will registers are books into which clerks copied wills being proved at the ecclesiastical courts. Sometimes a will might survive in the book when the original copy of it has been lost, providing a useful second chance for researchers.

The wills in the registers are listed in the three volumes of Wills at Chelmsford, but do not currently appear on Seax. To make these records easier to find, we have started a project to add the details of individual wills in the registers to Seax, so they will be searchable by name. To begin with, only a written catalogue description will be available, but in the long term we plan to add digital images too. In the meantime, registered wills are viewable on microfiche in the Searchroom, or copies can be ordered through our reprographics service.

The first register for which details have been added to Seax is that for the archdeaconry of Colchester (D/ACR 1) which covers the north of the county for the years 1500-1515.

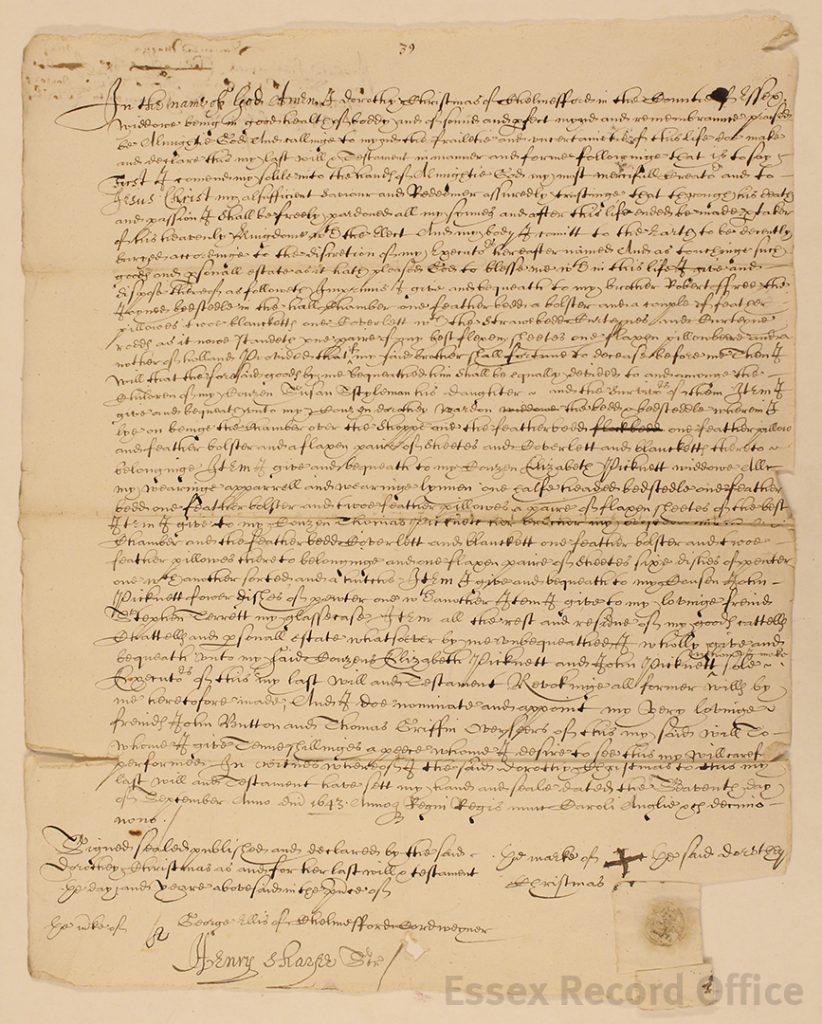

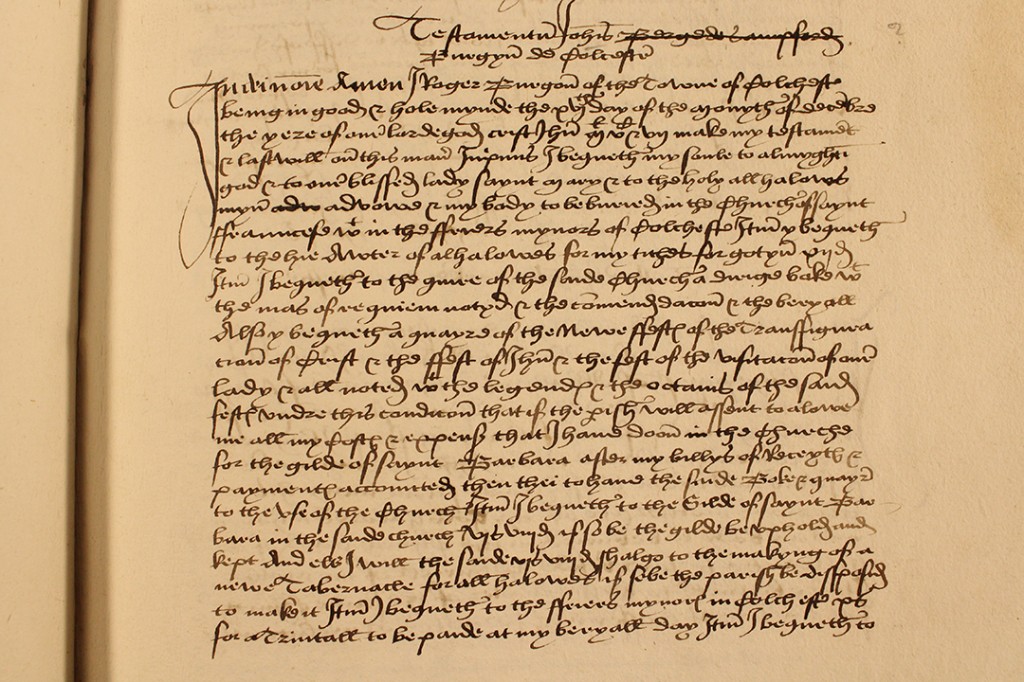

Some of the wills in the volume are in Latin and as it dates from before the Reformation, the testators would all have been Roman Catholic, evidenced by the use of Catholic phraseology such as ‘I bequeath my soule to almyghte god and to our blessed lady saynt mary and to the holy all hallowes’, which appears in the will of Roger Burgon of Colchester below. Following the English Reformation and the invention of the Church of England references to Mary and the saints all but disappeared.

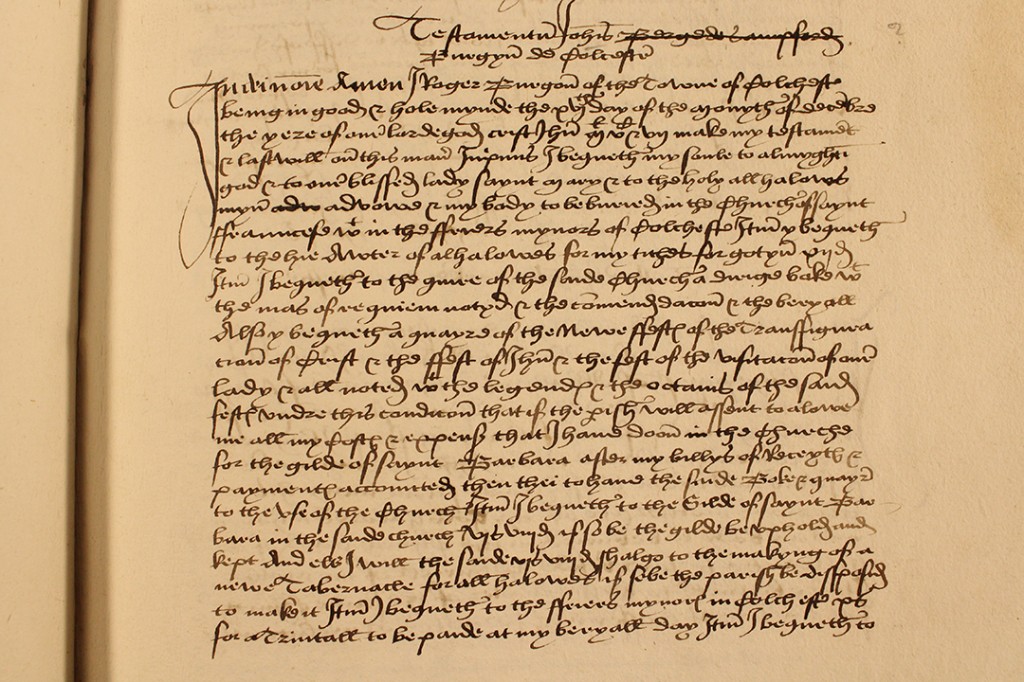

Roger Burgon’s will is dated 16 December 1507 (D/ACR 1/127/1). After bequeathing his soul to God he went on to request that his body be buried in the Church of St. Francis within the Convent of the Friars Minor [Greyfriars] in Colchester.

The beginning of the will of Roger Burgon, 1507 (D/ACR 1/127/1)

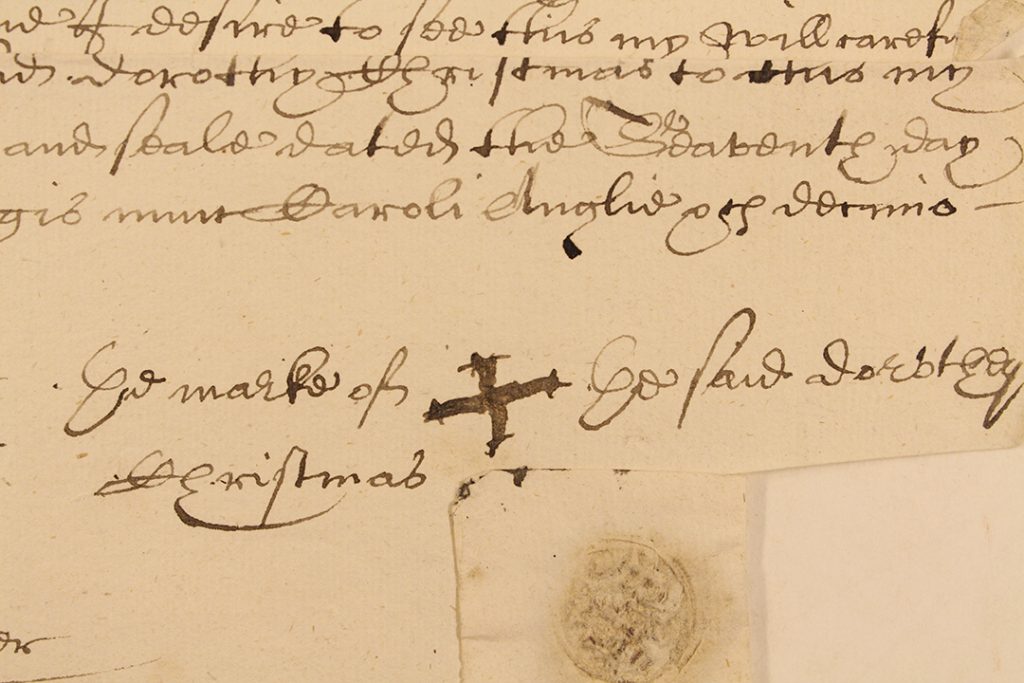

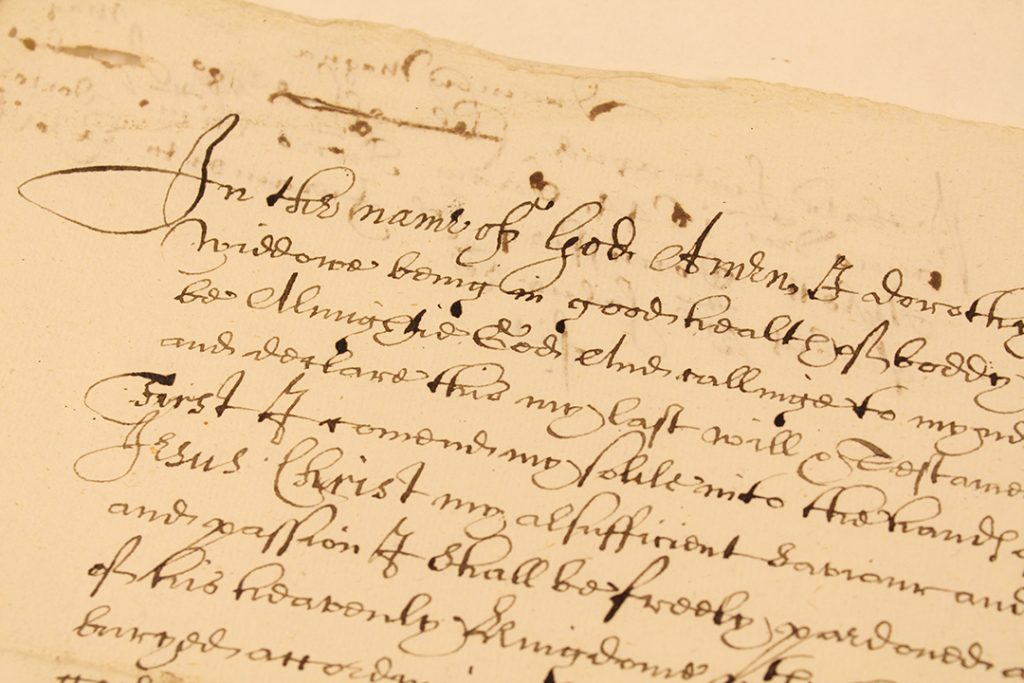

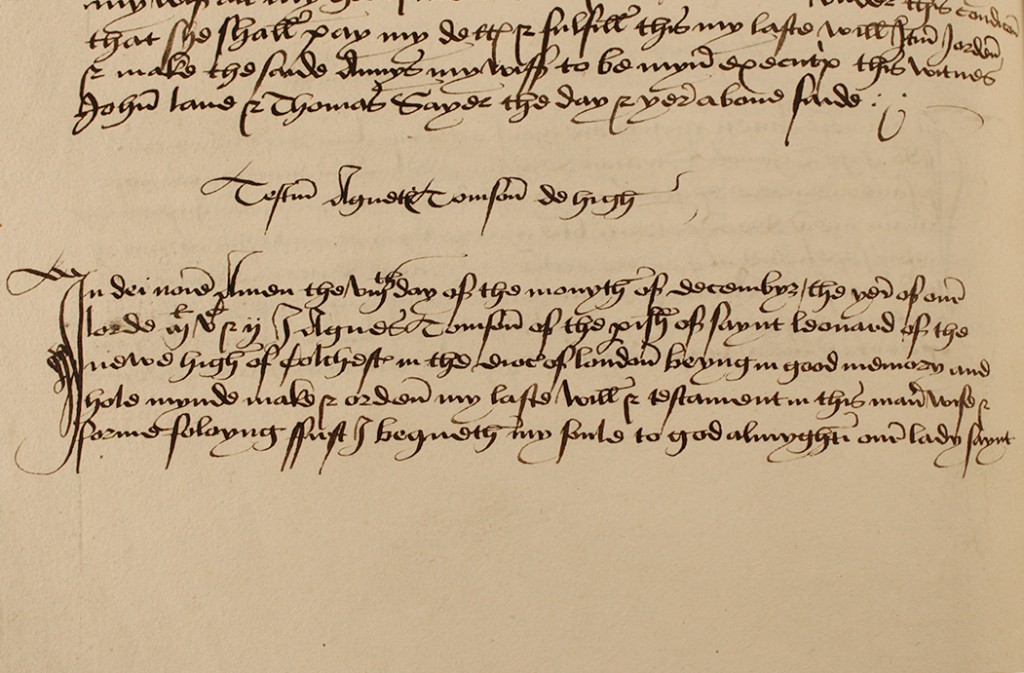

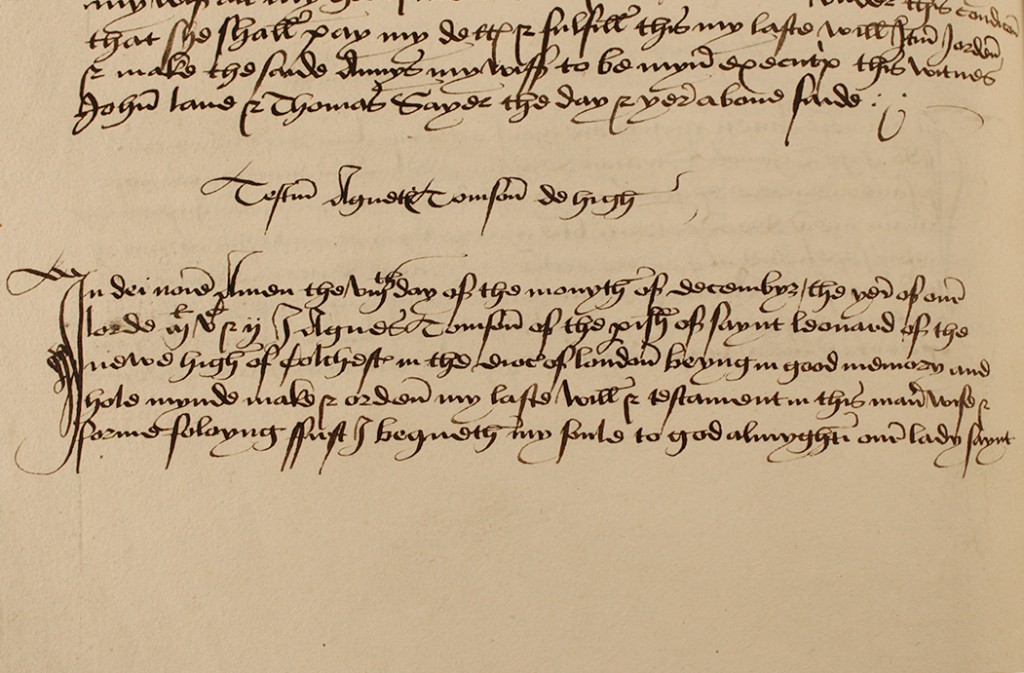

The majority of the wills are for men, but a number of women do appear, such as this one for Agnes Tomson of the parish of St Leonard in Colchester, dated 8th December 1502 (D/ACR 1/50/5).

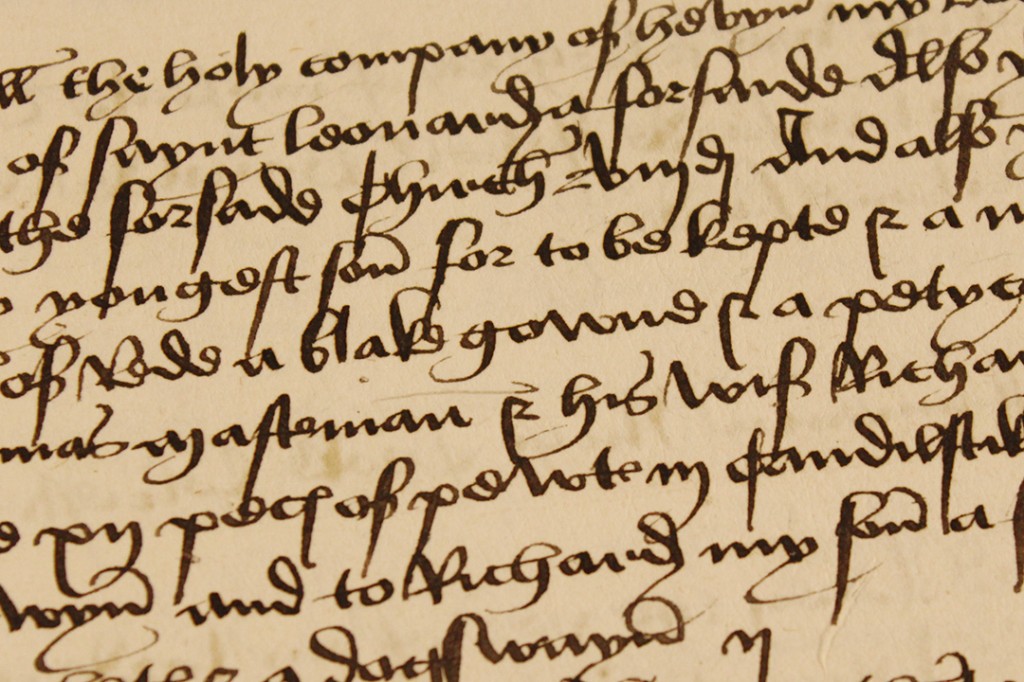

The beginning of the will of Agnes Tomson, 1502 (D/ACR 1/50/5). The heading to the will reads ‘Testm Agness Tomson de High’ – Testament of Agnes Tomson of the High, then a new area of Colchester

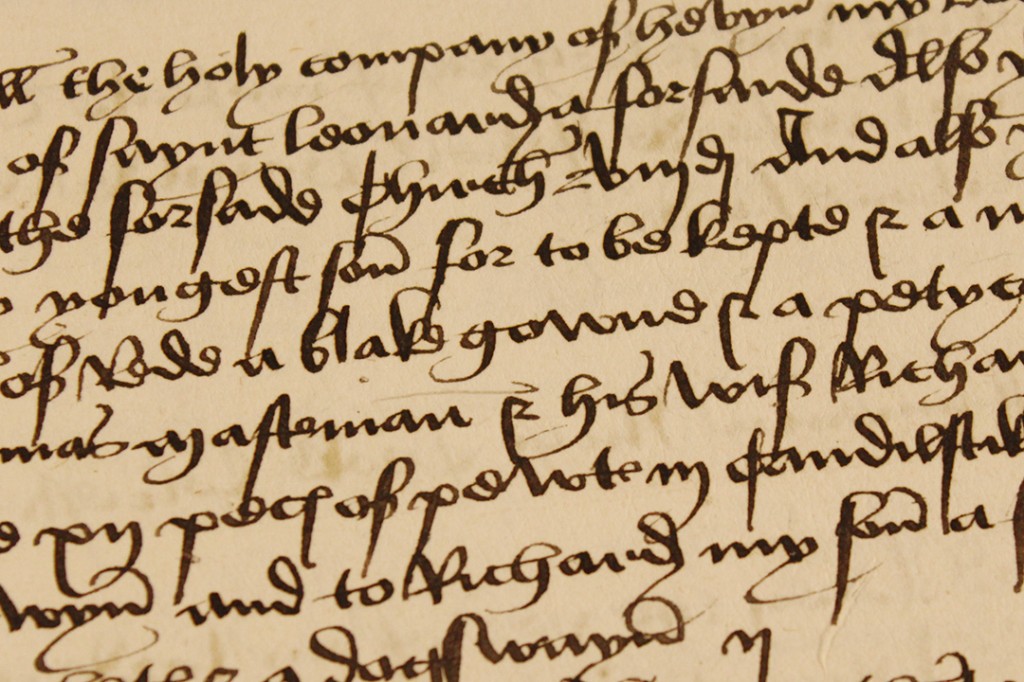

Agnes’s bequests included a ‘blake gowne’ (black dress), a ‘petycote’, a ‘greene gowne’, a ‘russet gowne’ a ‘floke bed’ (flock bed), pots, plates and a kettle, a ‘blankett’, a ‘bolster’, and a ‘long knyff’ (knife), all of which helps us build up a picture of Agnes’s life.

The section of Agnes’s will leaving a ‘blake gowne’ (black dress)

If you would like any further advice on using wills in your research, please ask a member of staff in the Searchroom or contact us on ero.enquiry@essex.gov.uk. If you would like any help with reading old handwriting, our publication Examples of English Handwriting 1150-1750 by Hilda Grieve is a very useful guide. It can be purchased for £6 (+P&P) from the Searchroom or by phoning 033301 32500.

If you would like any further advice on using wills in your research, please ask a member of staff in the Searchroom or contact us on ero.enquiry@essex.gov.uk. If you would like any help with reading old handwriting, our publication Examples of English Handwriting 1150-1750 by Hilda Grieve is a very useful guide. It can be purchased for £6 (+P&P) from the Searchroom or by phoning 033301 32500.

If you get really stuck, our Search Service can transcribe wills for you – please contact ero.searchroom@essex.gov.uk for details.