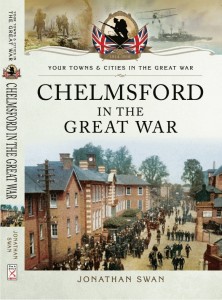

Ahead of his talk at ERO as part of the Essex Book Festival, we caught up with author Jonathan Swan, whose new book Chelmsford in the Great War is just about to be published. Join us for Jonathan’s talk on his book Chelmsford in the Great War on Saturday 14 March, 11.00am-12.30pm. Tickets £6, please book in advance on 033301 32500.

Ahead of his talk at ERO as part of the Essex Book Festival, we caught up with author Jonathan Swan, whose new book Chelmsford in the Great War is just about to be published. Join us for Jonathan’s talk on his book Chelmsford in the Great War on Saturday 14 March, 11.00am-12.30pm. Tickets £6, please book in advance on 033301 32500.

How did you come to write Chelmsford in the Great War?

Not quite sure! I have been researching First World War military medicine for a number of years and during negotiations with Pen & Sword Publishing my editor happened to mention a major series they were commissioning, “[Your Town] in the Great War”. This sounded interesting, so I spent a weekend in the library to see if there was enough material and sent in a proposal. And eighteen months later we have a book!

What sort of sources did you use to piece together your history of First World War Chelmsford, and where did you find them?

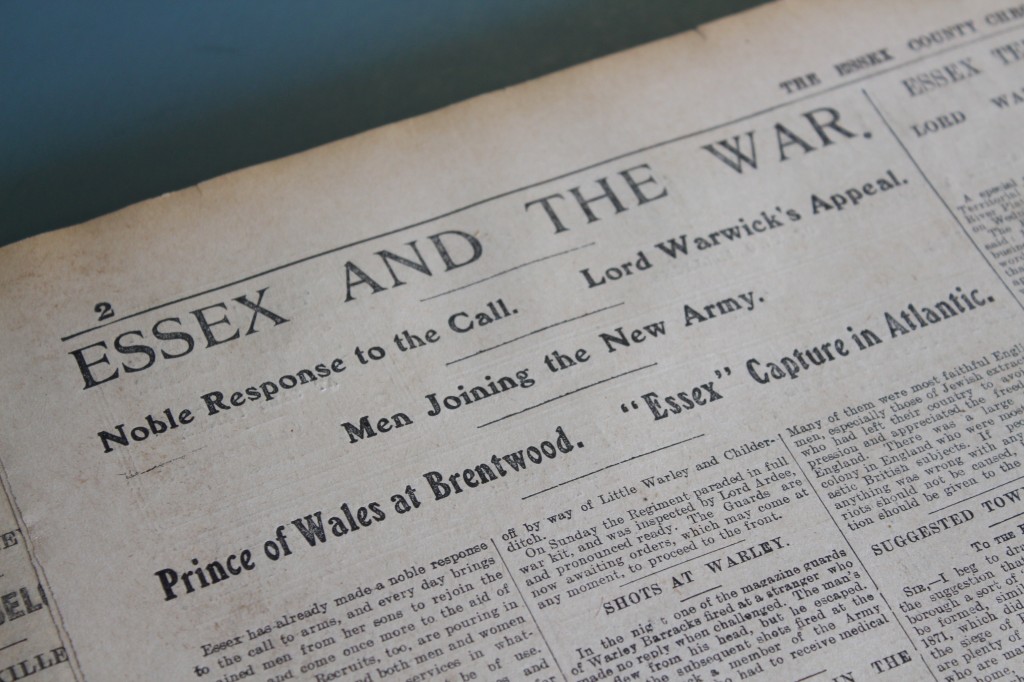

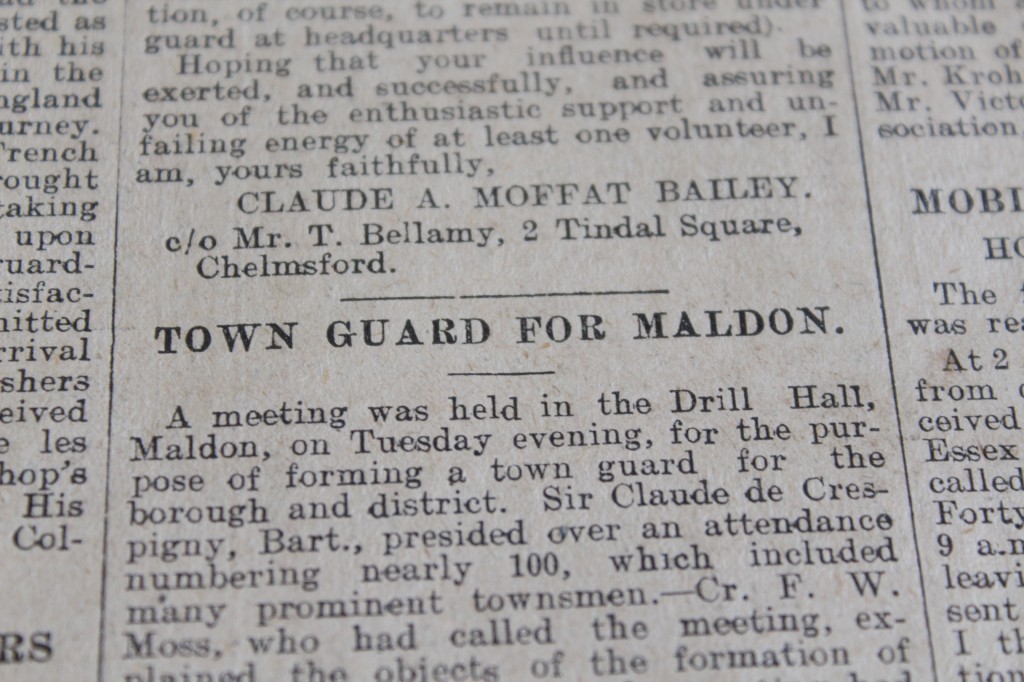

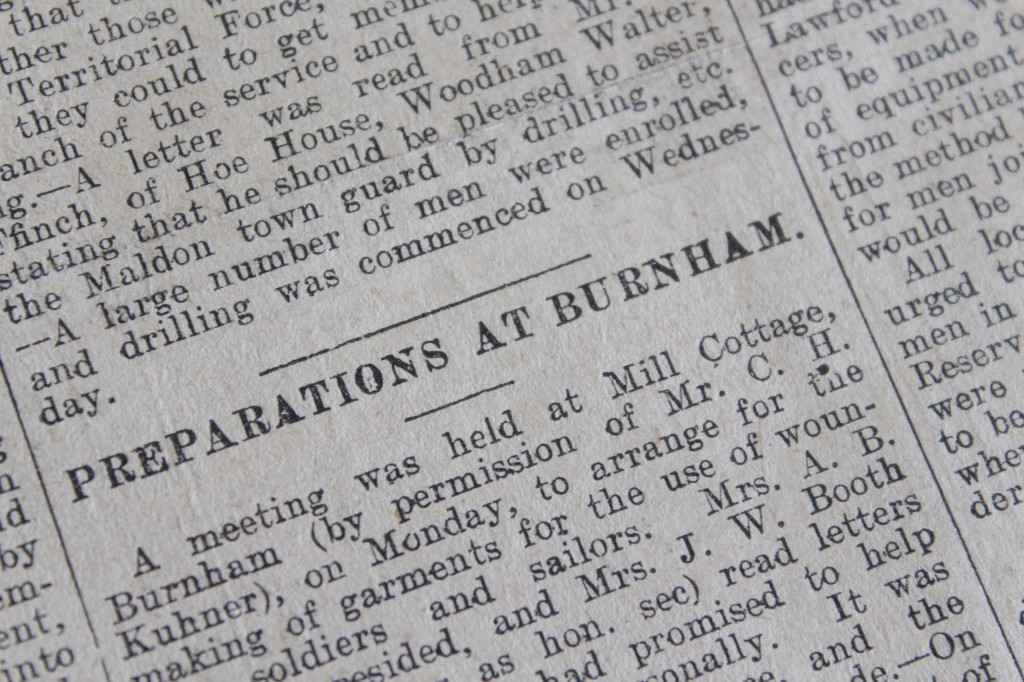

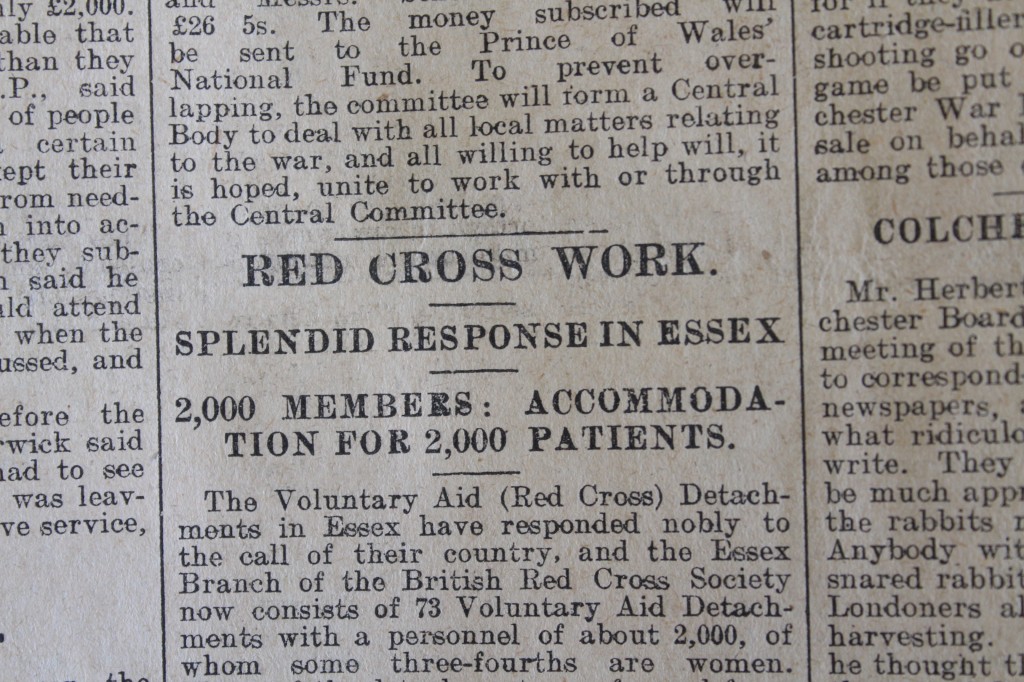

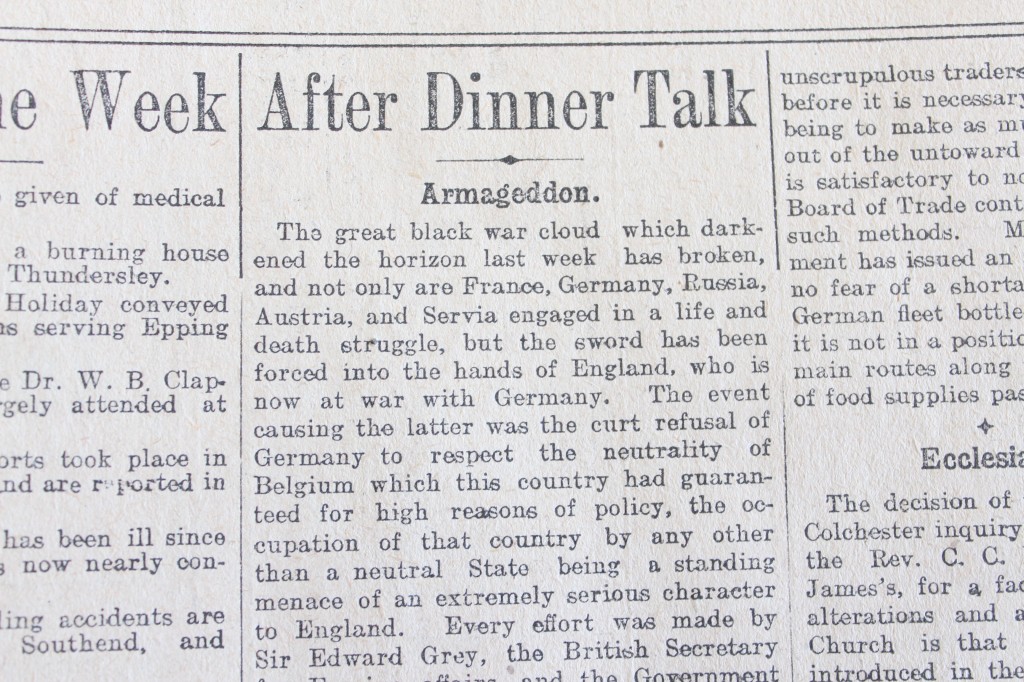

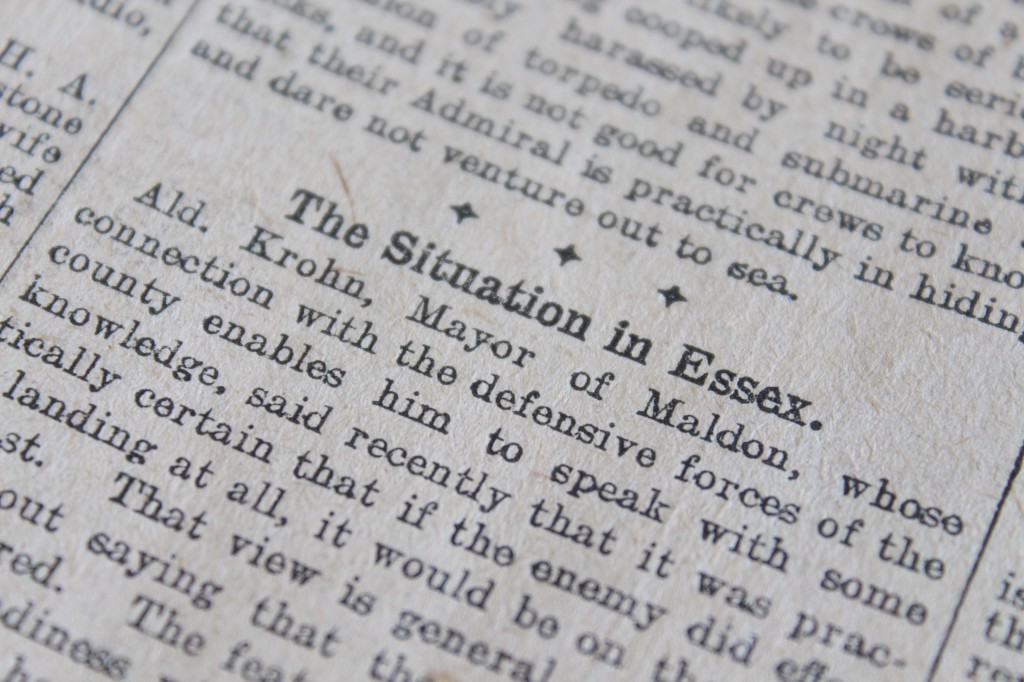

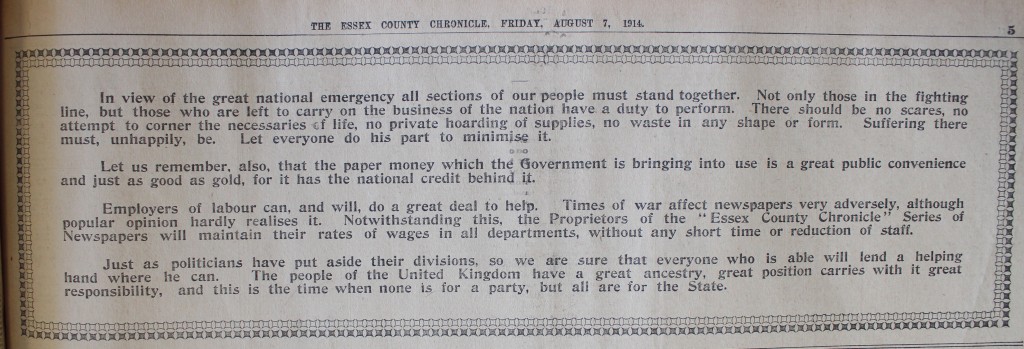

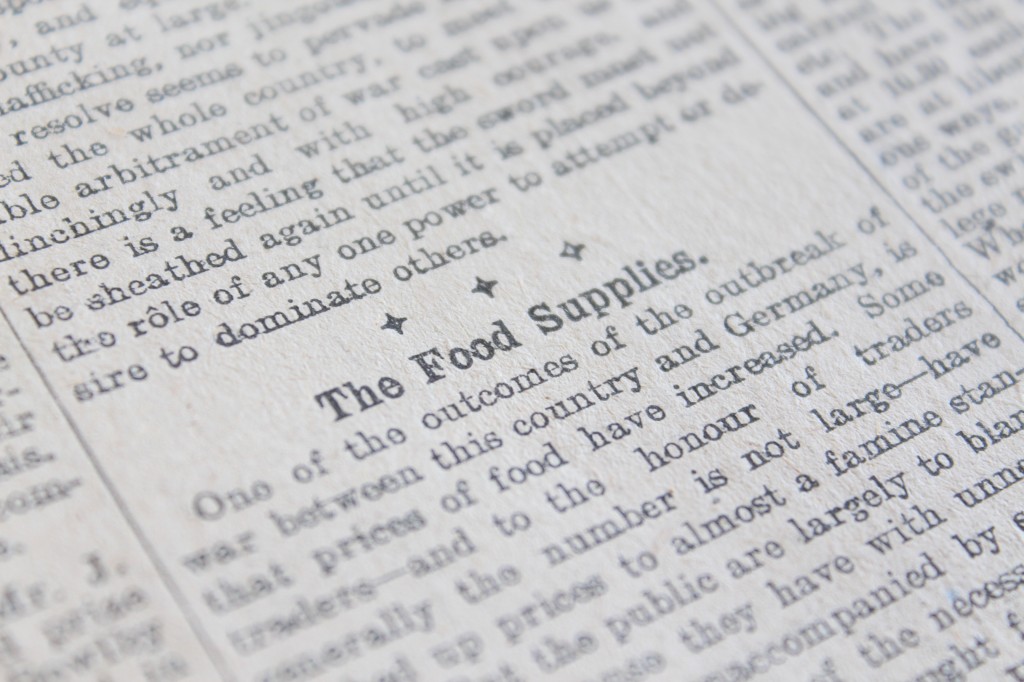

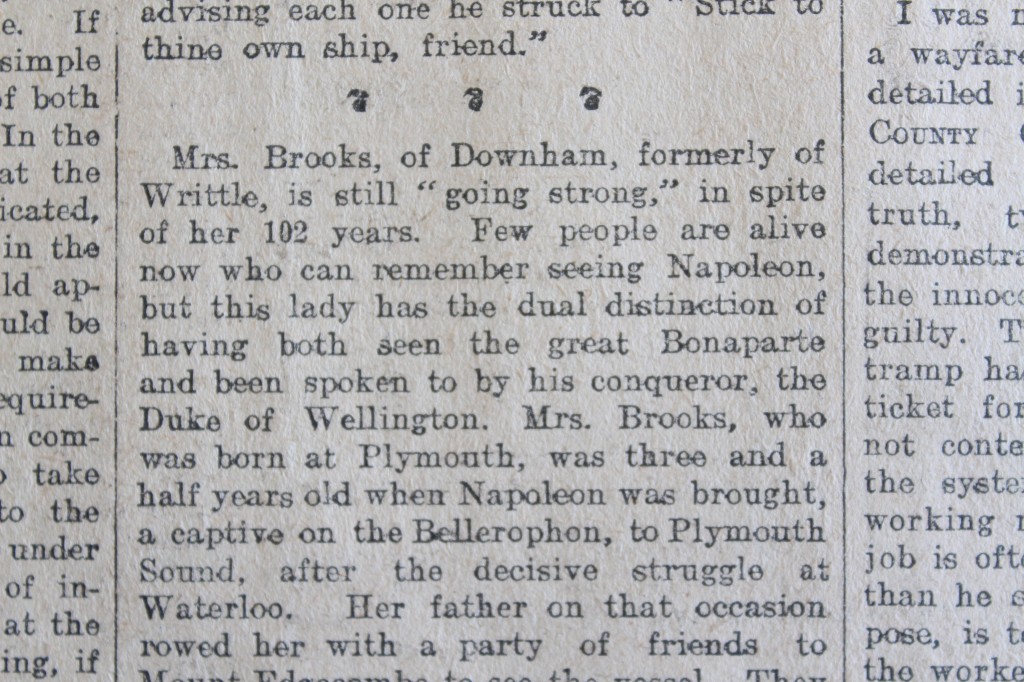

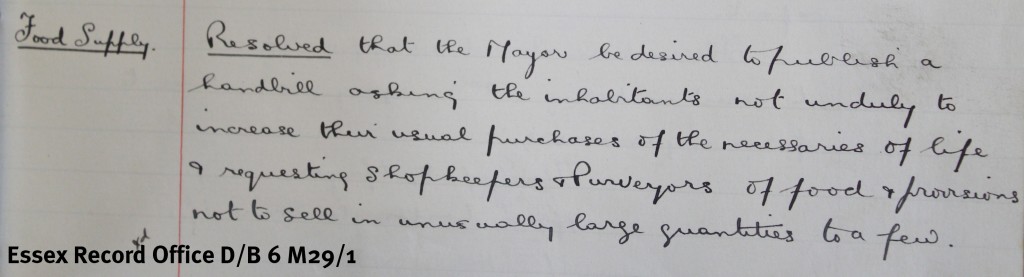

The library was my starting point, but Essex Record Office proved a great resource for maps, photographs and the wartime council minutes and other papers and records. Online resources such as the British Newspaper archive were invaluable.

What was the most surprising thing you found during your research?

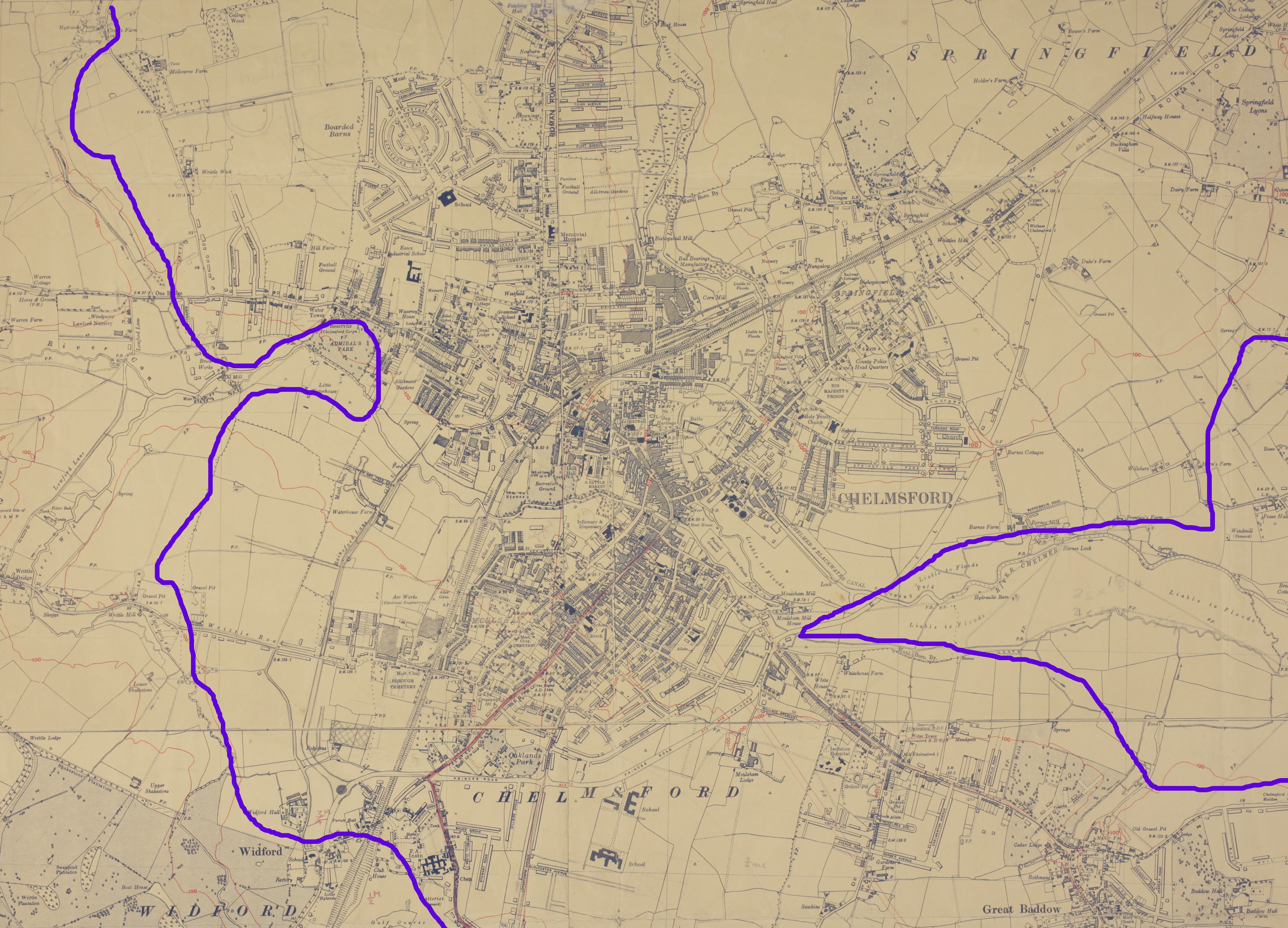

Great War Chelmsford was so much smaller than it is today, and roads like the Parkway have completely altered the urban landscape. Not a huge surprise, but it made it difficult to understand how people moved around the town; the High Street was central to everything. The railway formed the western and northern boundary of the town and, as Basil Harrison put it in his “Duke Street Childhood”, the corner of Duke Street and Broomfield Road was the start of the countryside!

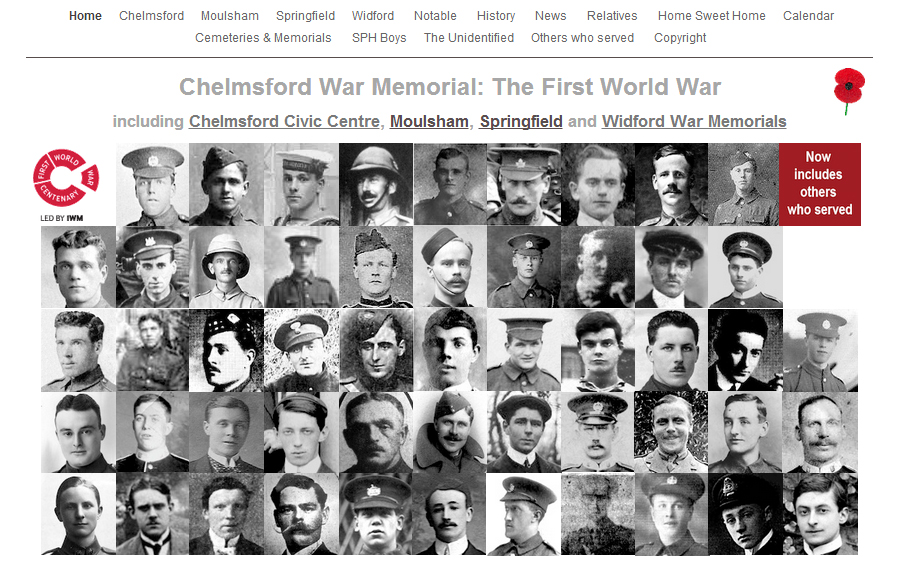

Ordnance Survey 6″:1 mile map of Chelmsford, 1919 with 1938 revisions. The approximate outline of the modern city is shown in purple. Click for a larger version.

Are there any stories that you found during your research that have particularly stuck with you?

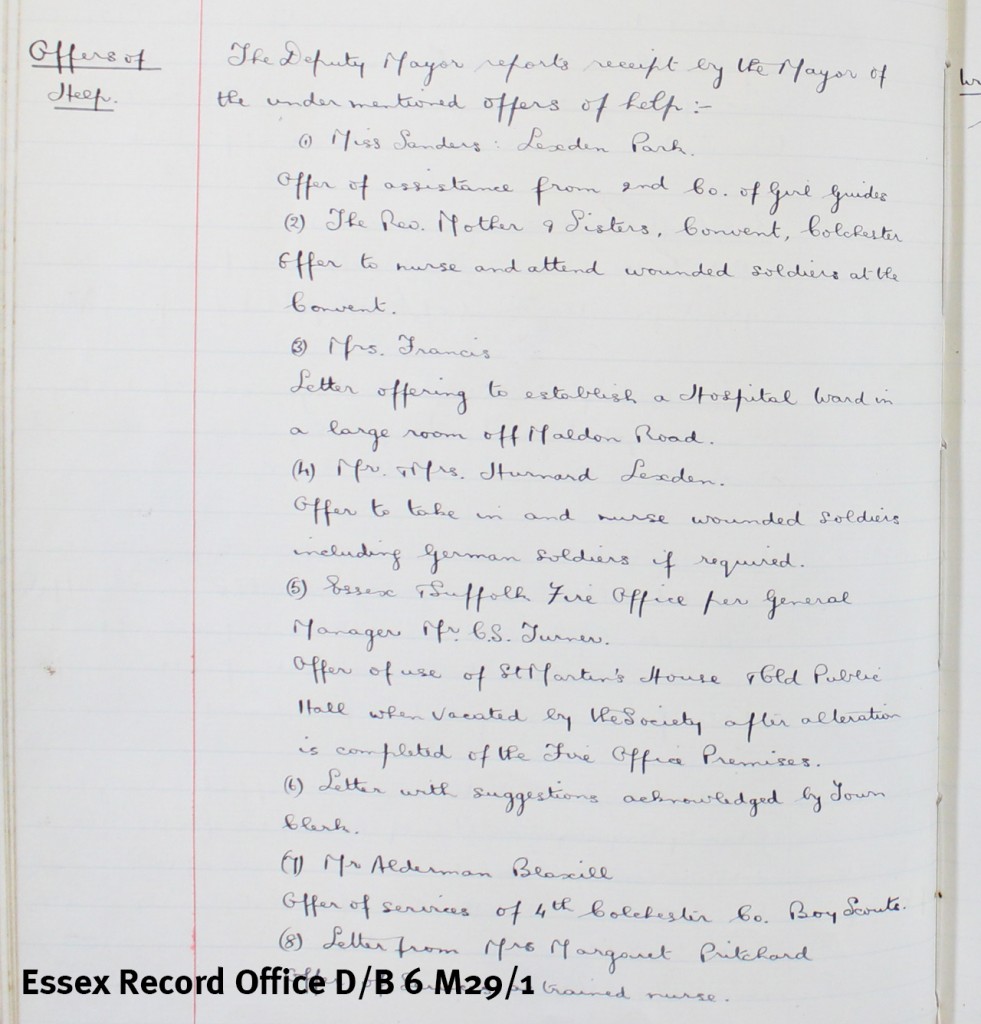

I’ve always been interested in local politics and democracy. In 1914 the council was made up of a number of unelected aldermen and a handful of councillors and they seemed to be incapable of civic leadership in the crisis – they didn’t believe in public air raid shelters, they didn’t want insurance for council property against bomb damage, they didn’t want public food kitchens, and there was a housing crisis because of all the additional munitions workers residing in the town and they did nothing about it. The high profile War Relief Fund did next to nothing because they didn’t think anyone merited assistance. The answer to any problem was to form yet another committee or subcommittee. And the idea of a conflict of interest appeared to have no meaning to them!

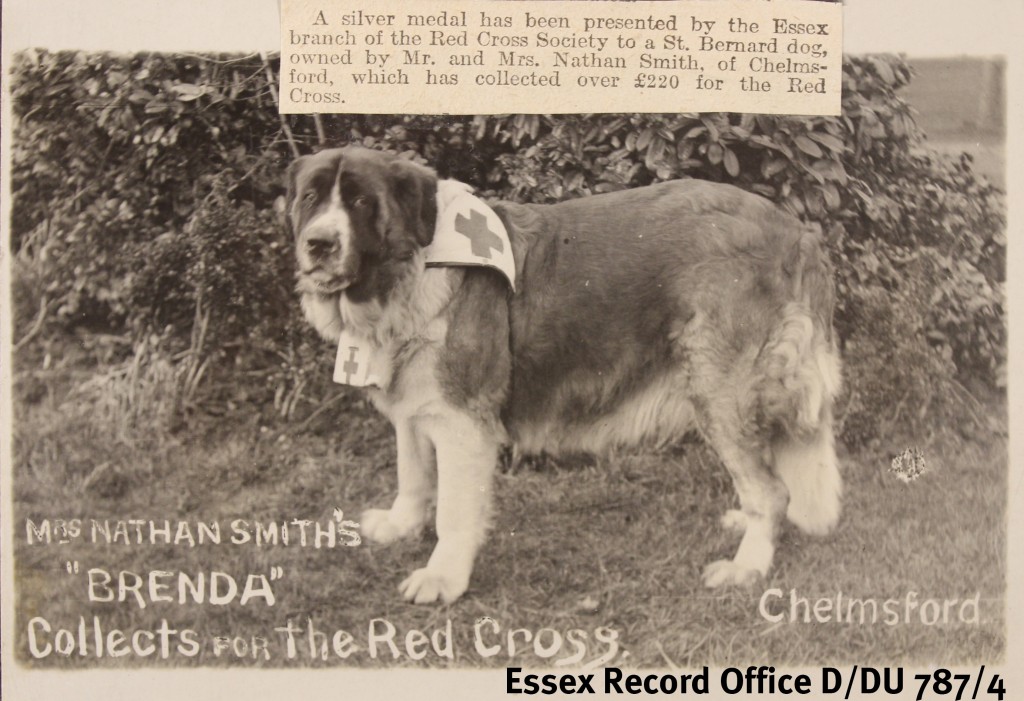

Chelmsford Brenda, the St Bernard dog who collected money for the Red Cross in Chelmsford during the First World War – one of the stories that Jonathan came across in his research (photo from scrapbook of Sir Richard Colvin, D/DU 787/4)

Do you have any family connections with the First World War?

My grandfather served in the Royal Army Medical Corps as a stretcher bearer. I followed in his footsteps by serving in the RAMC as a laboratory technician.

Is this your first book?

My first book was actually a text book on financial modelling, which is my day job. I’m currently working on the third edition. I’ve also written articles on corporate governance, local history, and military medicine.

Are you a full-time author?

I wish!

What is your connection with Chelmsford? We moved here from Newham in 2007. Both of my sons attended Boswells School. I spend some of my spare time interfering with the affairs of Essex County Council, Essex Police, Chelmsford College, and Anglia Ruskin University.

Where is your favourite place in Essex?

Anywhere I can go fishing!

What advice would you give to someone thinking of writing a history book?

A common mistake is to assume history is simply about dates and events. Good history books have a story to tell – it isn’t just what happened, it’s also why. And you must be selective: you will find fascinating little snippets about this or that, which may only amount to a sentence or two. I’ve left out a lot of material that didn’t really add any value – Corporal Rutland was tragically shot dead by his own pistol when showing it to a comrade in the Cherry Tree pub – interesting, but it doesn’t link to anything else. Conversely I’ve left out stories which merit a whole chapter or even a book of their own – Chelmsford teachers at war is a good example. A final point is that there are some very clever people out there, so make sure you can support any statements you make!