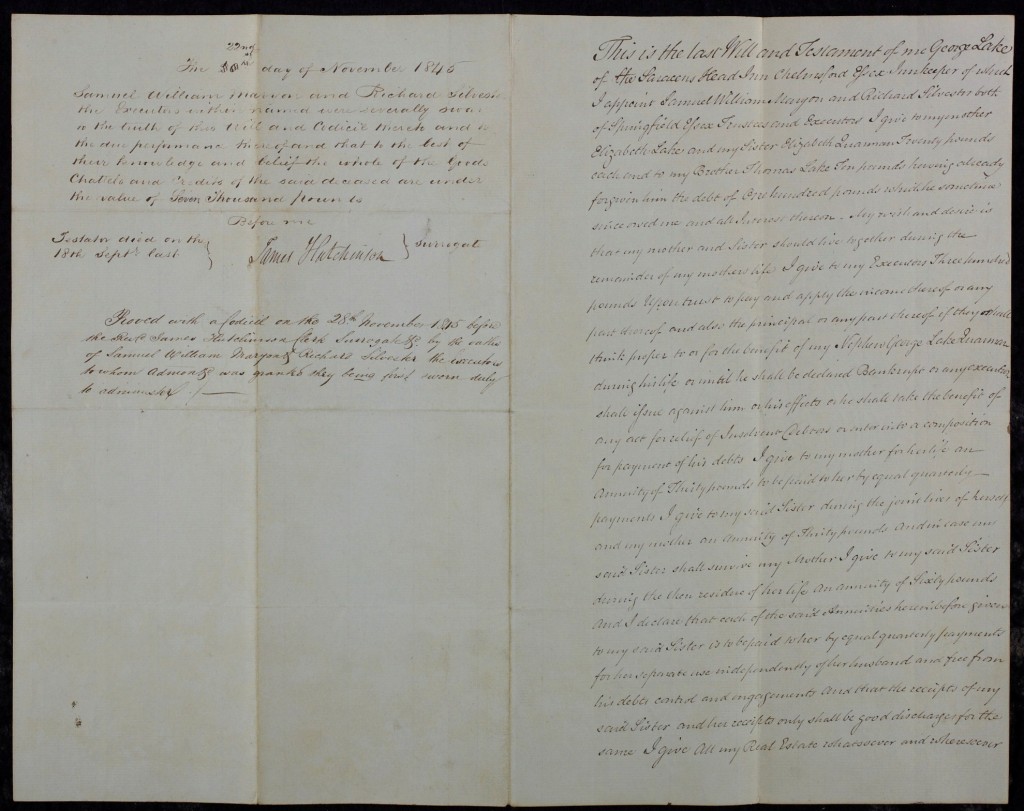

Archivist Katharine Schofield tells us about her choice for February’s Document of the Month.

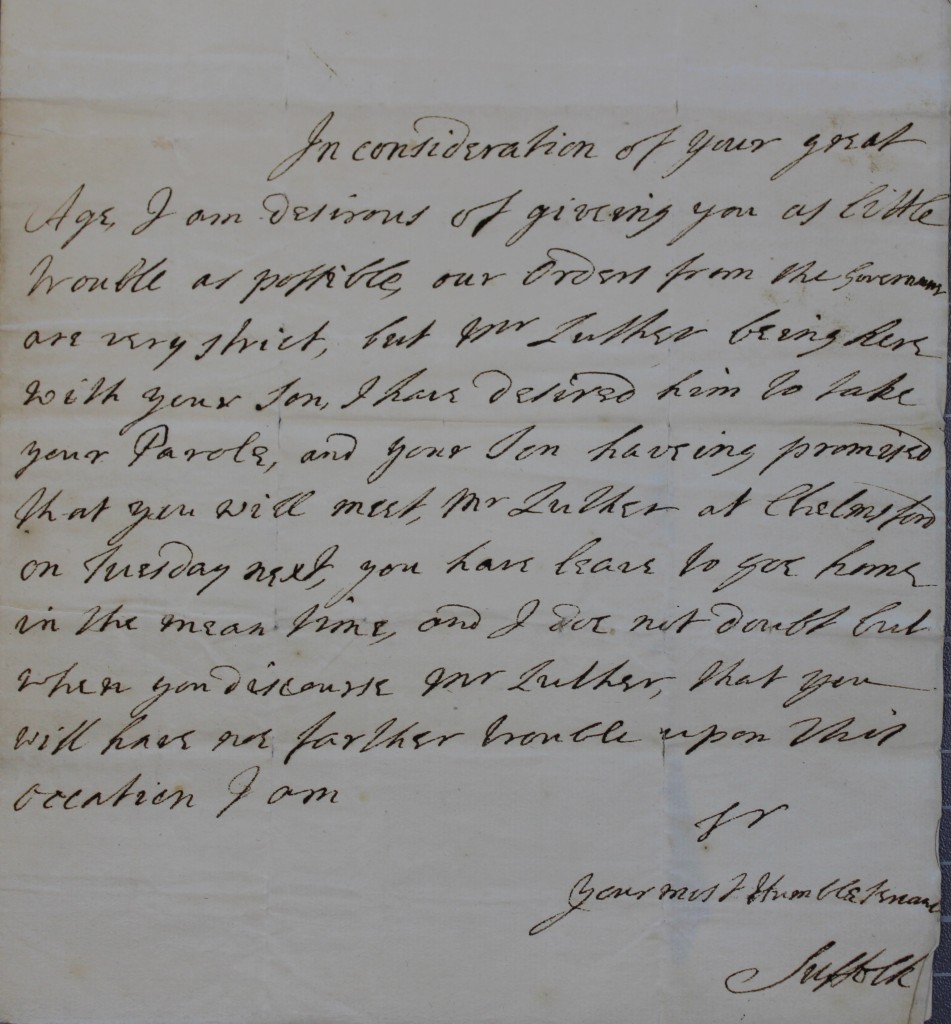

From the mid-17th century onwards, holders of public office were required to take oaths swearing allegiance to the monarch, denying the right of the deposed Stuart family to the throne, declaring the monarch to be the Supreme Governor of the Church of England, and denying the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that during the ceremony of the Mass the bread and wine offered miraculously become the body and blood of Christ). In effect, this meant that public offices were denied to Roman Catholics, who would not have been able to swear to such things.

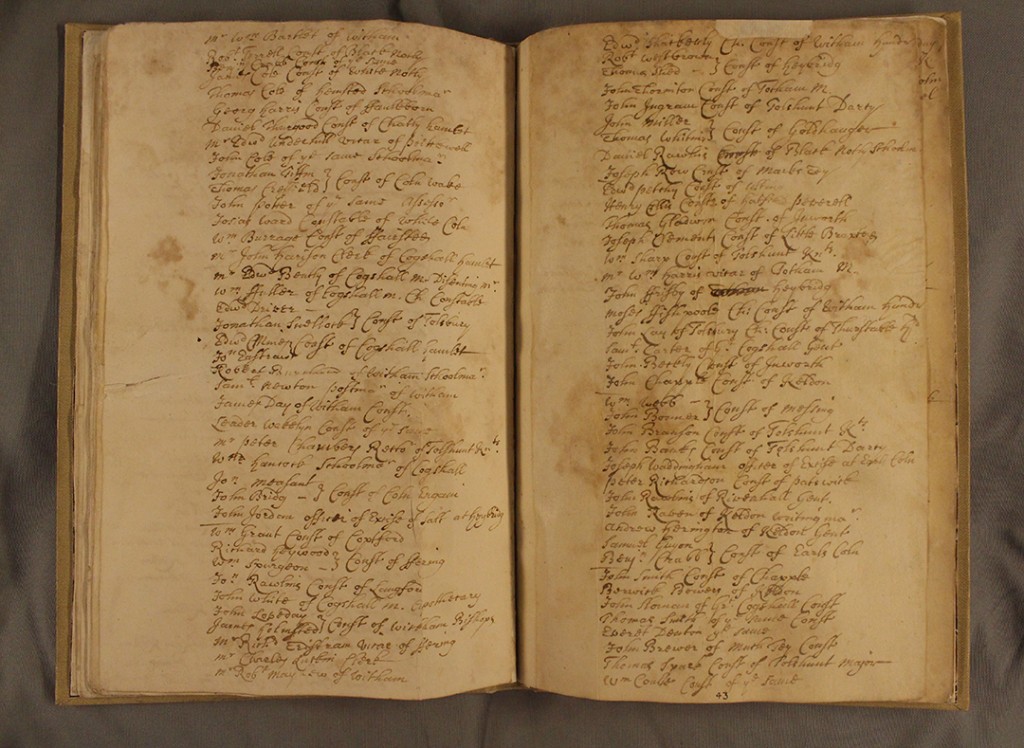

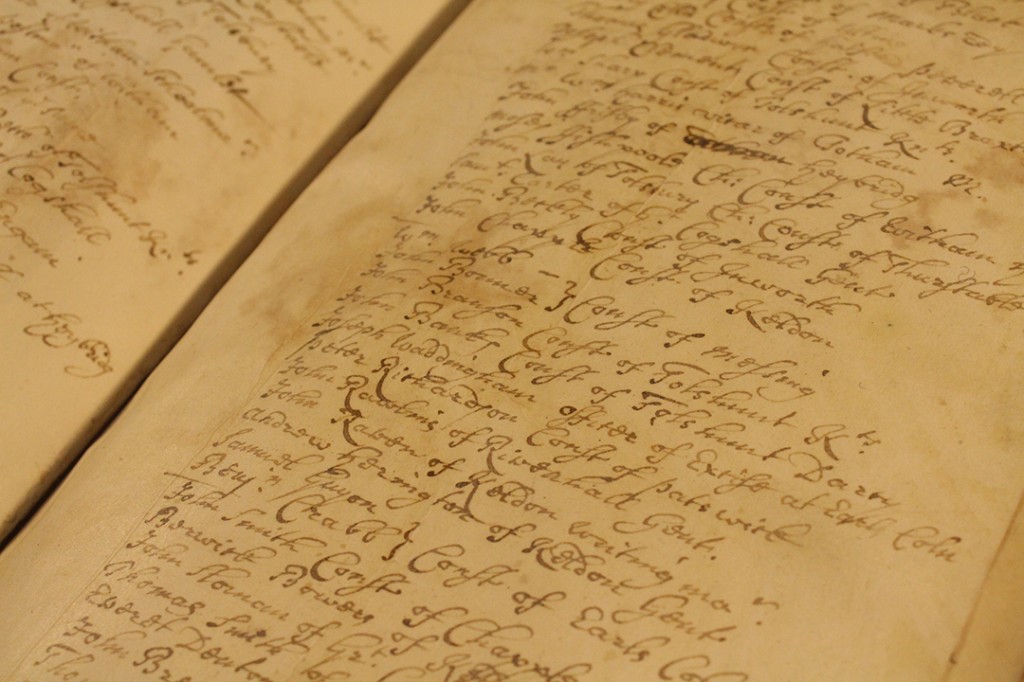

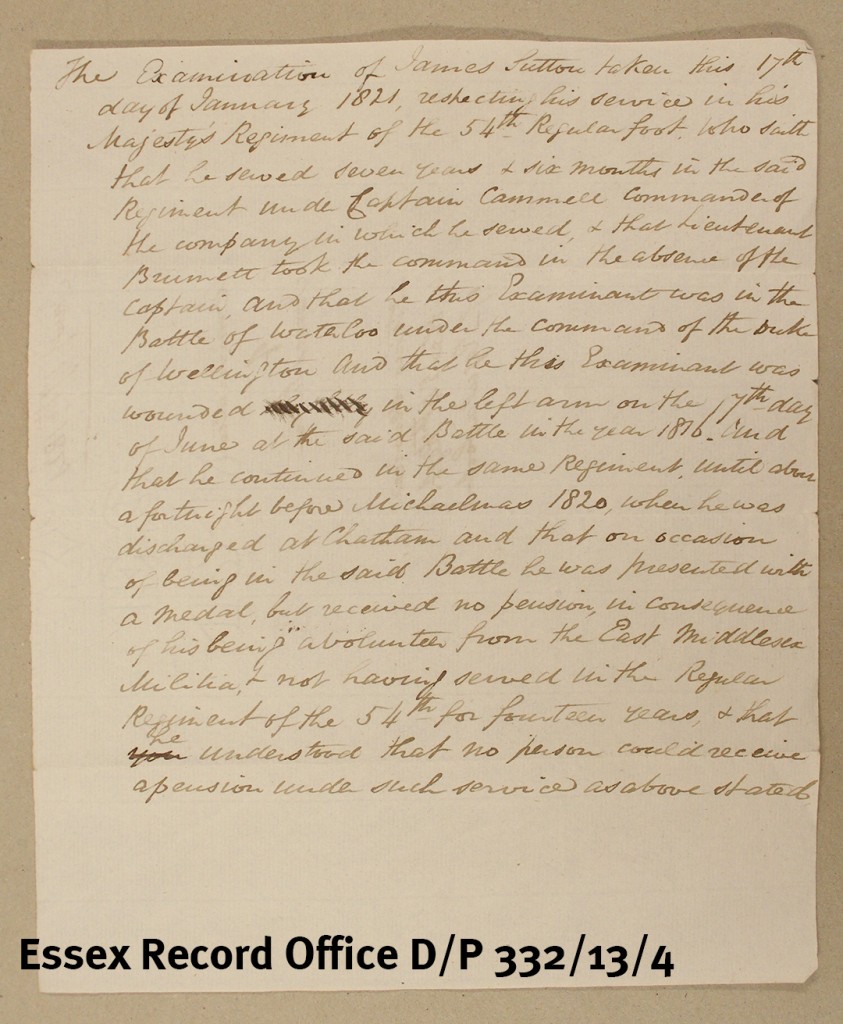

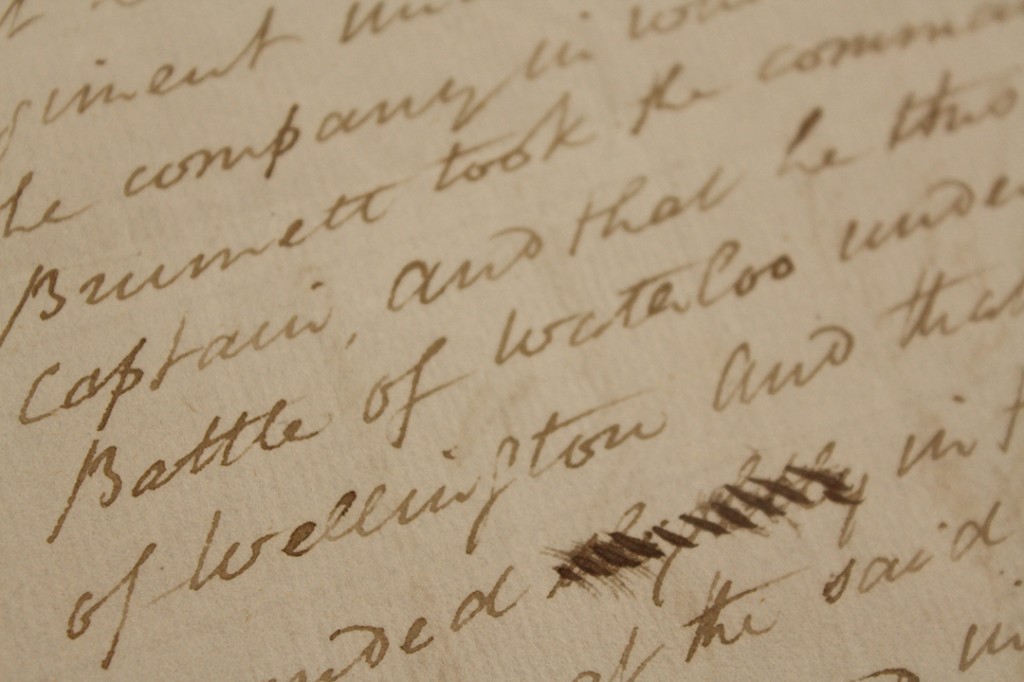

This oath book (Q/RRo 1/5) is part of the records of the Essex Quarter Sessions – the county authority which preceded the County Council. The book records details of those who had taken local public office, and who therefore swore the required oaths of allegiance, abjuration and supremacy, and made a declaration against transubstantiation.

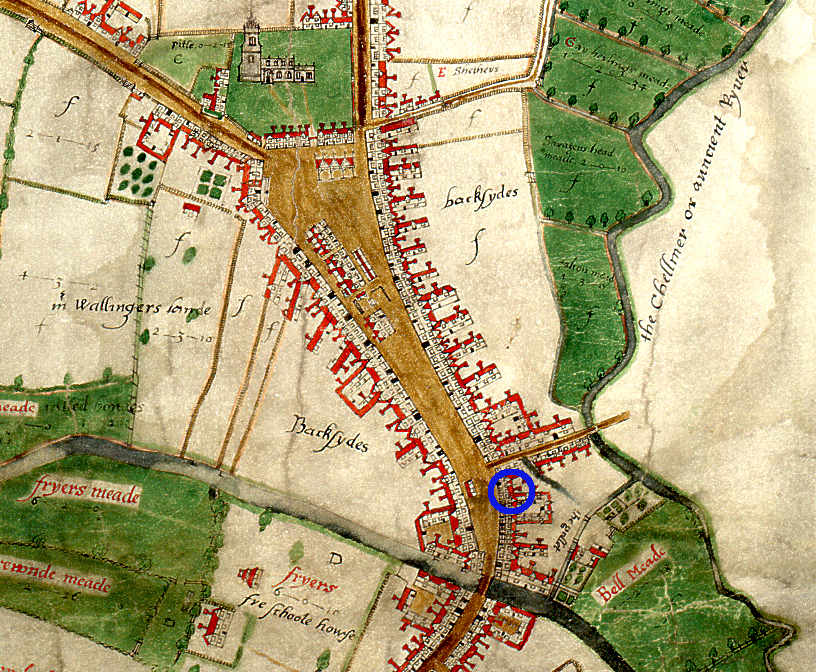

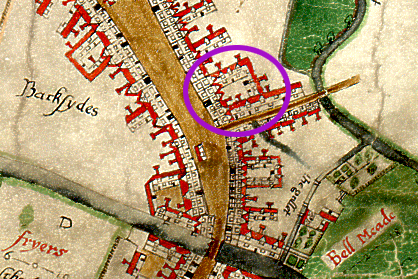

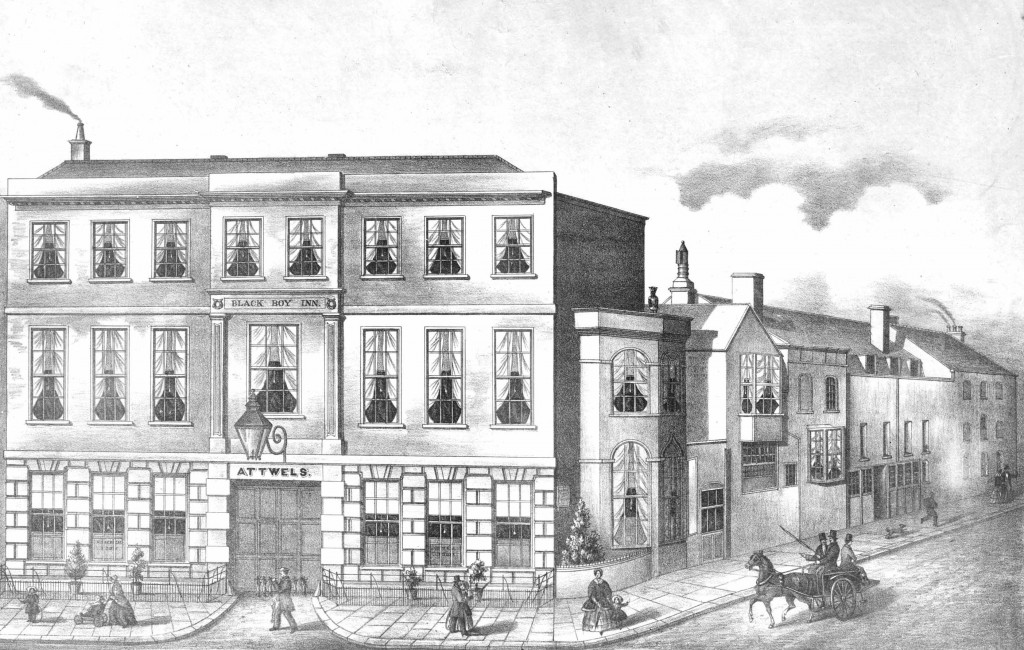

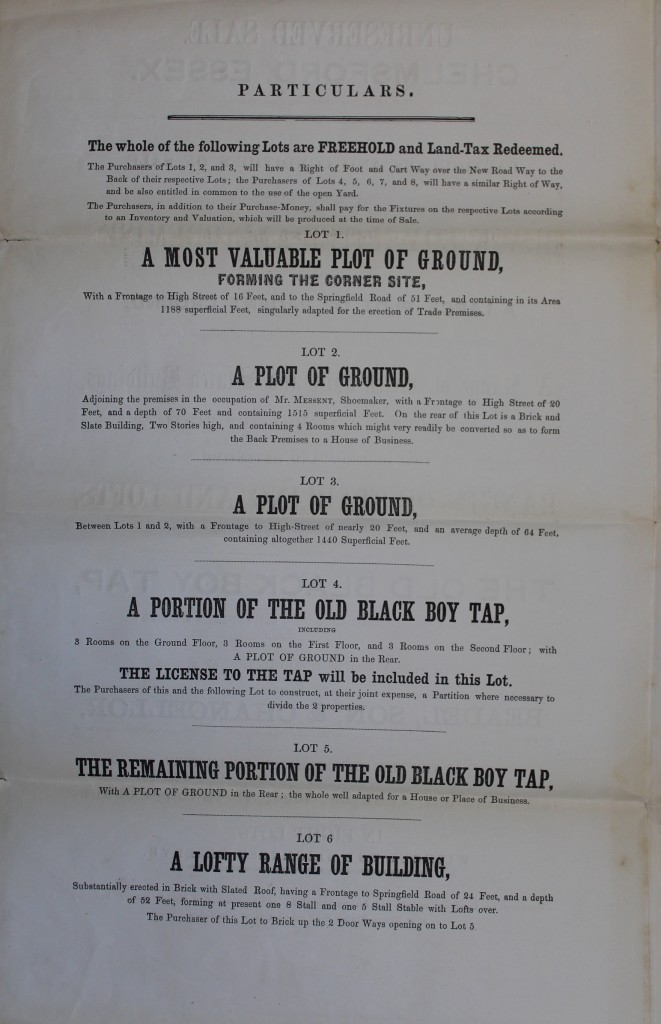

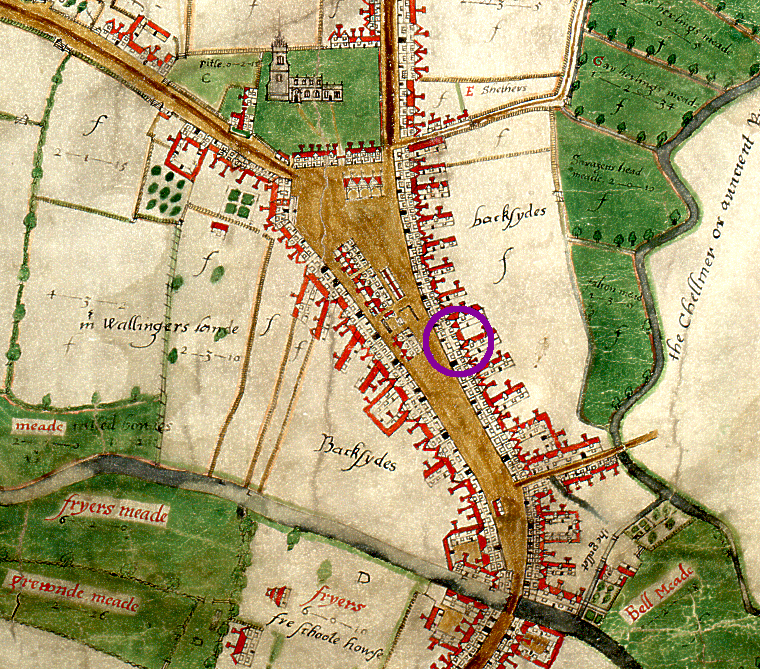

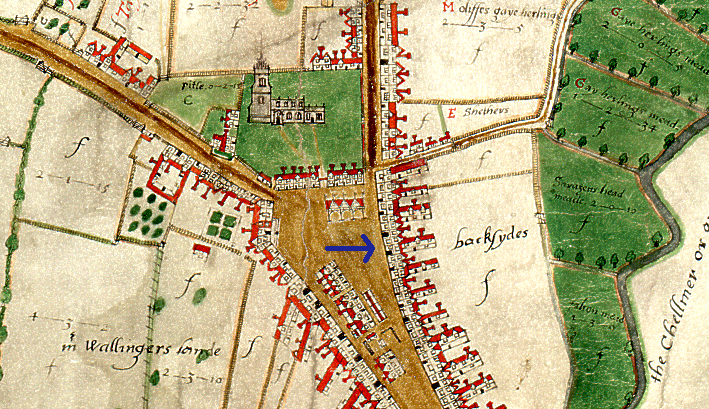

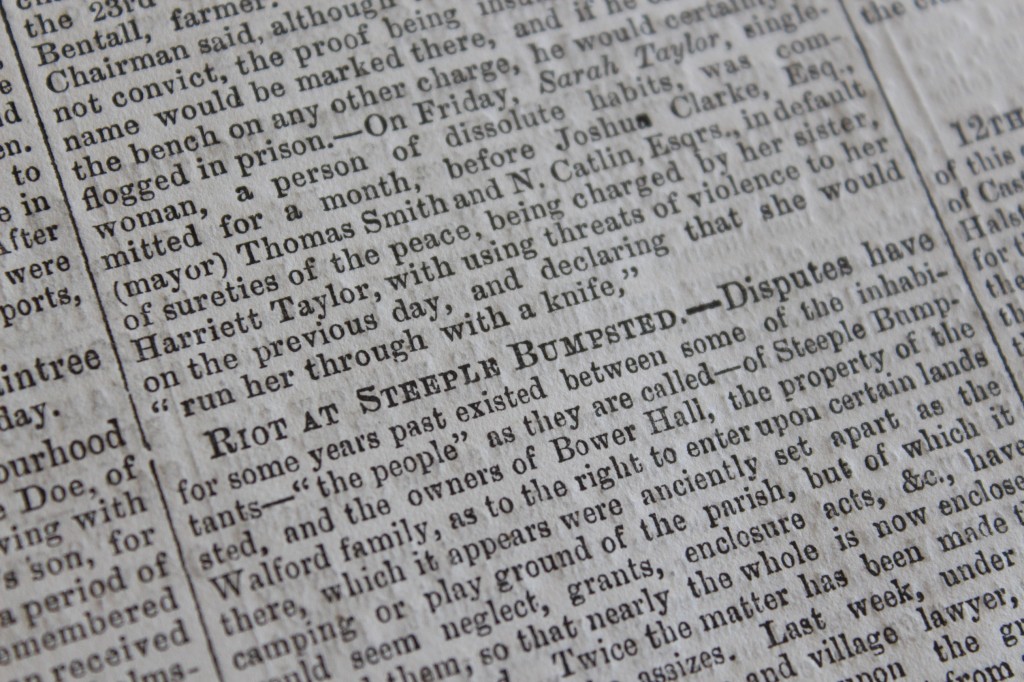

The whole book contains about 1,000 names, with parishes and occupations of those subscribing between 1714 and 1716. Special sessions were held in various places in Essex to make it easier for people to travel. These names were recorded at an adjourned Quarter Sessions held at the Angel in Kelvedon on 13 December 1715 at the height of the Jacobite Rebellion. The next session was held at the Old Tavern in Colchester the following day and records those from the north-east of the county.

The names in this opening are mostly from central Essex. Most of those recorded are parish and chief constables of hundreds. Church of England ministers also took the oaths and those listed here include the incumbents of Prittlewell, Tolleshunt Knights, Feering and Great Totham, as well as the Revd. Edward Bently, dissenting minister of Coggeshall. Four schoolmasters from Hempstead, Prittlewell, Witham and Coggeshall are among the names recorded here, together with a number of other public officials – Samuel Newton, postmaster of Witham, John Jorden ‘officer of Excise of Salt at Heybridg’, Joseph Waddingham, excise officer at Earls Colne and John Potter of Wakes Colne, assessor. Also listed are John White of Coggeshall, apothecary and John Raven of Kelvedon, writing master.

Quarter Sessions records contain all sorts of useful and fascinating details helpful for a range of different types of research. They encompass a huge range of topics, from cases heard by the Quarter Sessions courts which sat four times a year, to the licensing of victuallers, printing presses and slaughterhouses, and the maintenance of highways and planning of railways and canals. The Quarter Sessions began in 1388 and lasted until 1971. The Essex Quarter Sessions records are among the earliest and most complete in the country, dating back to 1555.

We are introducing a new workshop for 2016 which will provide a closer look at the fascinating snapshots of life in the past that these records provide. Discover: Quarter Sessions Records takes place on Wednesday 11 May 2016, 2.00pm-4.00pm. Tickets are £10 and need to be booked in advance on 033301 32500.