This guest blog post is by Marion E. Colthorpe, who has been investigating the people and places visited by Queen Elizabeth I since the 1970s. Her work expanded until she had discovered the whereabouts of the Queen on every day of her reign, along with what she was doing and who she was with. This research has included many different kinds of document, including a good number of records from the Essex Record Office. The results of Marion’s research, totalling 3,324 pages, have recently been published online by the Folger Shakespeare Library as The Elizabethan Court Day by Day. Here she shares with us how churchwardens’ accounts help to trace the Queen’s travels.

When I began to trace Elizabeth I’s whereabouts throughout her reign I made sure to read every churchwardens’ account I could find, because whenever the Queen passed through or even near a parish it was obligatory for the church bells to be rung; if they were not the Queen’s Almoner levied a fine, and the church door was sealed up until the fine was paid. There are a number of payments for ringing, and a fine for not ringing, in the accounts held by the Essex Record Office. (In Essex, as in other counties, considerably more parish registers have survived than churchwardens’ accounts, so there are a limited number to select from).

On her first ‘progress’ through Essex and Suffolk in 1561, on her way from Sir William Petre at Ingatestone, whose lavish expenditure is described in F.G. Emmison’ s Tudor Secretary: Sir William Petre (London, 1961), Chelmsford St Mary (now Chelmsford Cathedral) paid [July 22] ‘To the ringers when the Queen came through the town, 6s8d; paid for drink for them, 12d’.

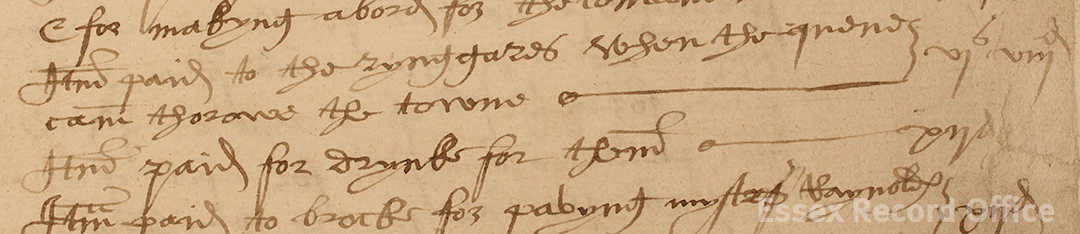

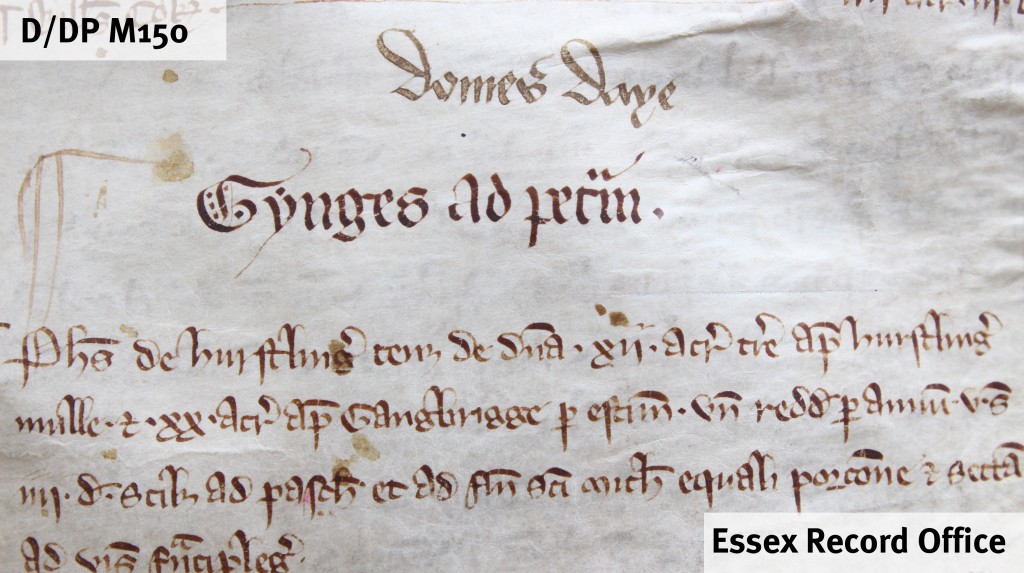

The accounts of the churchwarden’s of St Mary’s in Chelmsford (D/P 94/5/1) include money paid to the bell ringers for their services in ringing the bells when the queen passed through the town, and for drink for them:

‘It[e]m paid to the rynggares when the queen cam thorowe the towne – vis viiid’

‘It[e]m paid for drynk for them – xiid’

The Queen sailed up the Orwell to Ipswich on August 5. On August 25, back in Essex, Great Dunmow wardens ‘Paid to the good wife Barker for ale for them that did ring when the Queen’s Grace came through the parish, 8d’. The Queen was on her way from Lord Rich, at Little Leighs (he founded Felsted School in 1564; his monument is in Felsted Church), to Lord Morley at Great Hallingbury.

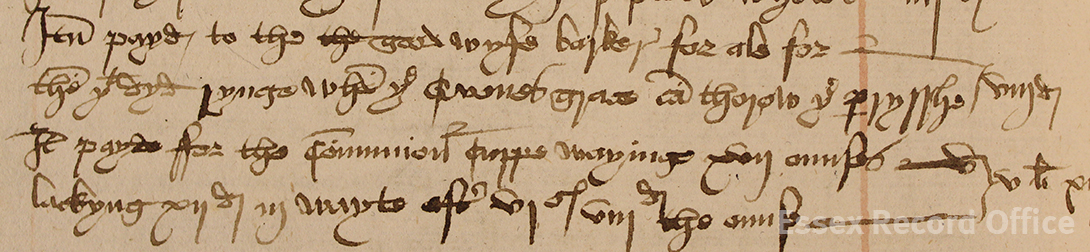

The Great Dunmow churchwardens’ accounts (D/P 11/5/1) include this payment in 1561: ‘It[em] payd to the good wife barker for ale for the[m] yt dyd rynge when ye Quenes grace ca[me] thorow ye p[ari]she – viii d’

In September 1579 the Queen stayed several days at New Hall, Boreham, with her close friends the Earl and Countess of Sussex, where entertainment included music, speeches by Jupiter and goddesses, and a tournament. Chelmsford St Mary ‘Paid for 8 ringers two days when the Queen’s Majesty was at New Hall, 6s8d; paid the same time to the Almoner’s man, for unsealing the church door, 5s’.

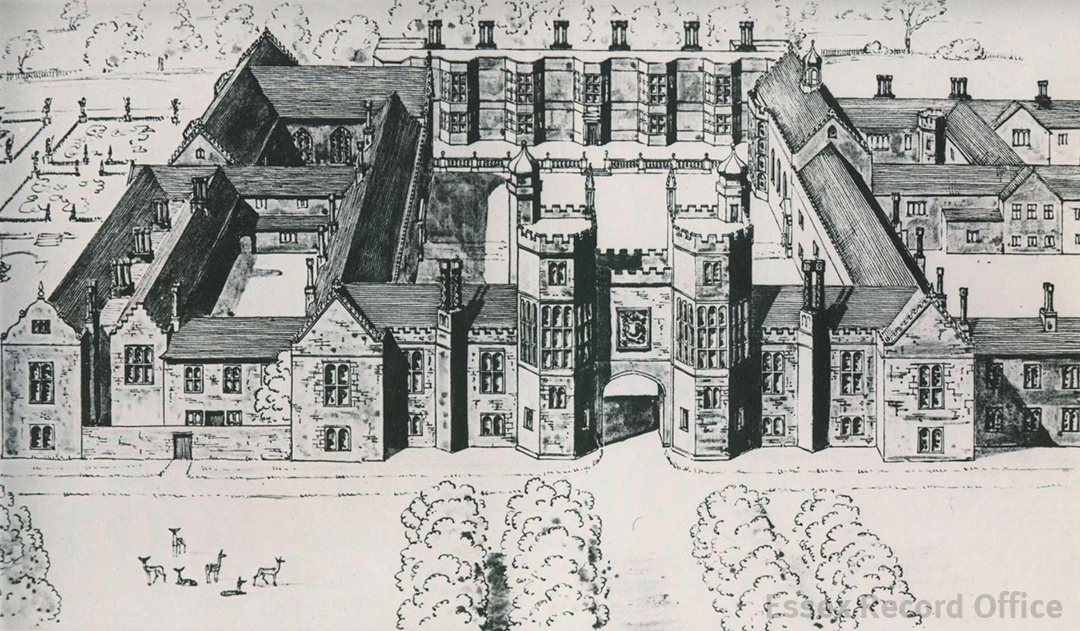

Drawing of New Hall Palace by Ian Dunlop, based on a ground plan of the palace, engravings by George Vertue and an engraving after a drawing in the Laurentian Library, Florence. From Palaces and Progresses of Elizabeth I, Ian Dunlop, 1962 (I/Mb 42/1/27)

The Earl of Sussex died on 9 June 1583 at his Bermondsey, Surrey, home. In his will he described in detail the hangings (tapestries) and furnishings at New Hall at the Queen’s visit. On July 8 his funeral procession left Bermondsey, was conducted through London by the Lord Mayor and Aldermen, and a Chelmsford churchwarden noted ‘About 6 or 7 afternoon with much royalty was the body of the right honourable Earl the Earl of Sussex and late Lord Chamberlain to the Queen’s Majesty brought through the town to New Hall to be buried in Boreham Church’. The funeral was next day at St Andrew’s, where his monument remains. By her own will in 1589 the Countess of Sussex founded Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge (with a bequest of £5,000).

From early in the reign it became the custom to celebrate the Queen’s Accession Day (17 November 1558). Thus in 1578 Great Easton paid ‘To the ringers the 17th of November 1578 to ring in token of Queen Elizabeth’s joyful entrance to the Crown of England, 20d’. The day was usually known (incorrectly) as ‘Coronation Day’, or ‘Crownation Day’, and also as the Queen’s day, the Queen’s night, the Queen’s holiday, or St Hugh’s day (being his feast day).

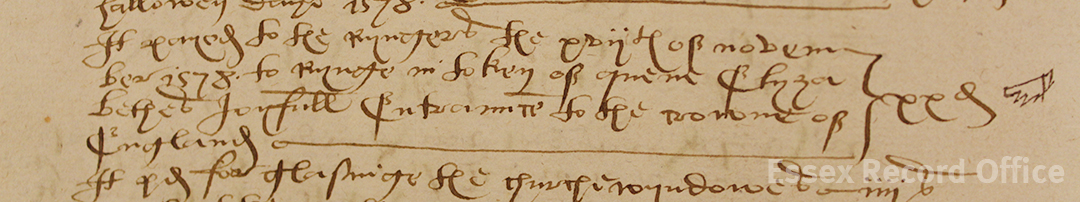

The Great Easton churchwarden’s accounts (D/P 232/8/1) record a payment to the parish bell ringers on 17th November 1578:

‘It[em] payed to the ryngers the xviith of November 1578 to rynge in token of queen Elyzabethes joyfull Entrance to the crowne of England – xxd’

It may be added that in other Essex records F.G. Emmison found several reports of fights in Essex churches on Coronation Eve and Coronation Day. (Elizabethan Life: Morals & the Church Courts (Chelmsford, 1973), chapter on ‘Religious Offences’).

The Queen’s birthday (7 September 1533) was also celebrated, but the custom was not widespread, although in Essex Hornchurch churchwardens made payments, such as in 1592: ‘Laid out for six ringers of the birthday of our most gracious Sovereign Lady Queen Elizabeth, 6d’. In contrast, on Accession Day there were 10 ringers, who received 10 shillings. In 1597 Hornchurch ‘Paid to the ringers when the Queen came to Havering and her birthday, 6d’. The Queen was at Havering royal manor-house from August 19-31, where she hunted in Waltham Forest.

Churchwardens also made occasional references to national events. There was a ‘great earthquake’ on 6 April 1580, when considerable damage was caused in London and southern England. The Archbishop of Canterbury issued an ‘Order of Prayer … to avert and turn God’s wrath from us … to be used in all Parish Churches’. Chelmsford St Mary paid on April 28 ‘For two books of prayers concerning the earthquake to be read in the church Wednesdays and Fridays, 8d’.

When the Queen decided to assist the Low Countries, in rebellion against their Spanish rulers, her principal favourite the Earl of Leicester passed through Essex on his way to Holland in December 1585. Chelmsford St Mary paid [Dec 4] ‘To the ringers at the right honourable the Earl of Leicester his coming through Chelmsford, 6d’; and in the same account ‘Laid out for two prayer books for the praying for the Queen’s Majesty, 8d’.

The Earl was again in Chelmsford in July 1588 when St Mary paid [July 24] ‘For ringing when my Lord of Leicester came, 12d’. The Earl wrote on July 25 from Tilbury Camp that he went to Chelmsford ‘ to take order for the bringing of all the soldiers hither this day’. On the most famous visit of her reign the Queen stayed overnight on August 8 at Edward Rich’s Saffron Garden house at Horndon-on-the-Hill; she made not one but several speeches at Tilbury.

A fleet commanded by Lord Howard and the Earl of Essex left for Cadiz in Spain in June 1596. The Queen herself had written a prayer ‘at the departure of the fleet’. Hornchurch paid 3d ‘For a book which was to pray for the fleet’. According to Francis Bacon, in just 14 hours on June 21 the Spanish Navy was destroyed and Cadiz was taken, one of the most notable exploits of the reign.

The Queen died on 24 March 1603. There would be no more payments such as that at South Weald Church in 1590: ‘Paid Weaver’s wife and is for the ringers’ dinners and suppers and for the next day ringing for the Crownation of our gracious good Queen whom God long preserve, Amen. 12s6d’.

![Extract from the compotus for the manor of Terling, 1328-1330 (D/DU 206/22), which records the purchase of a watermill [molend’ aquatic] from Prittlewell [Priterewelle] to be moved to Terling.](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/D-DU-206-22-Terling-compotus-crop-1024x287.jpg)