Following our recent posts on what a manor was, and the records produced by manorial courts, today we have the final instalment in our manorial mini-series from Archivist Katharine Schofield. Running a manor produced all sorts documents, which record boundaries, customs and obligations owed between tenants and lords – read on for just a few examples. You can find out more about manorial records and how you can use them in your own research at Essex through the ages: tracing the past using manorial records on Saturday 12 July 2014.

Imagine you are lord of a medieval manor. You might even own several manors, and they might be scattered around a county, or indeed the country.

To make sure you are making the most of your manors (and getting the most from your tenants), you are going to need to establish how much and what type of land your manors include, how much your manors cost to run, and how much income you can expect to get from them.

All of this took a great deal of estate management, and has left us with a rich archive of administrative records. This includes extents, surveys and custumals, accounts or compoti, and later maps, rentals, perambulations and terriers. Handily for the modern researcher, they were often produced in English from as early as the 15th century.

Custumals

Custumals record the customs of a manor; that is, the labour services and rents owed by tenants in return for their lands, and any obligations owed to or by the lord. The famous Dunmow Flitch ceremony, for example, has its origins in a custom of the manor of Little Dunmow.

The extent and custumal of 1329-1330 from the manor of Stansgate in Steeple (which survives as a copy of c.1450 (D/DCf M34)), records a number of customs, including the obligation of all tenants resident in Ramsey Island, Steeple and Stansgate with their own boats or barges to take the Prior of Stansgate (the priory owned the manor), monks and servants by water to and from Maldon market every Saturday with their food. In return the Priory would give them dinner on the following Sunday.

Surveys, maps, terriers and perambulations

These are all different types of document that establish the boundaries of a manor, and which bits of the manor were held by which tenants.

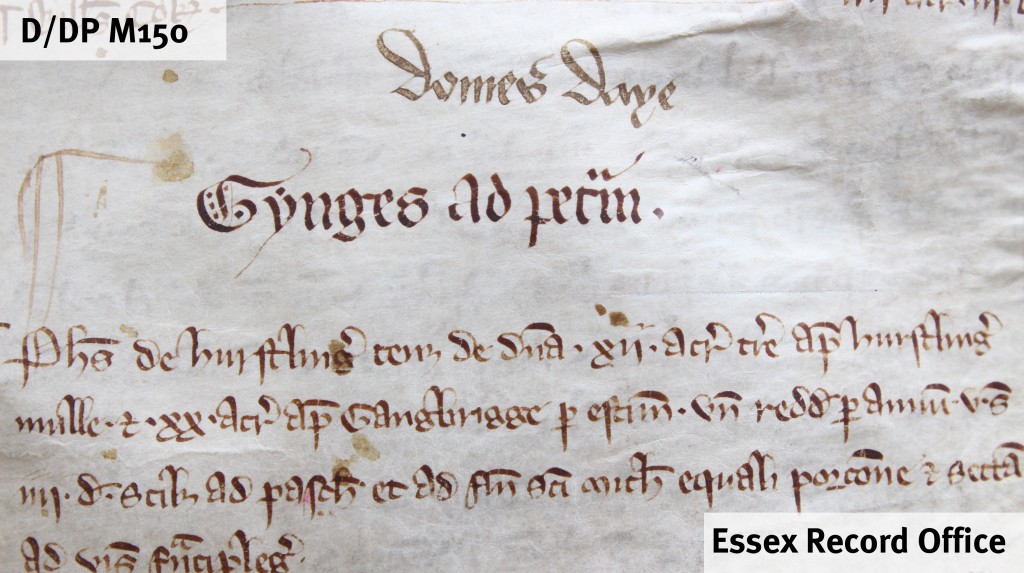

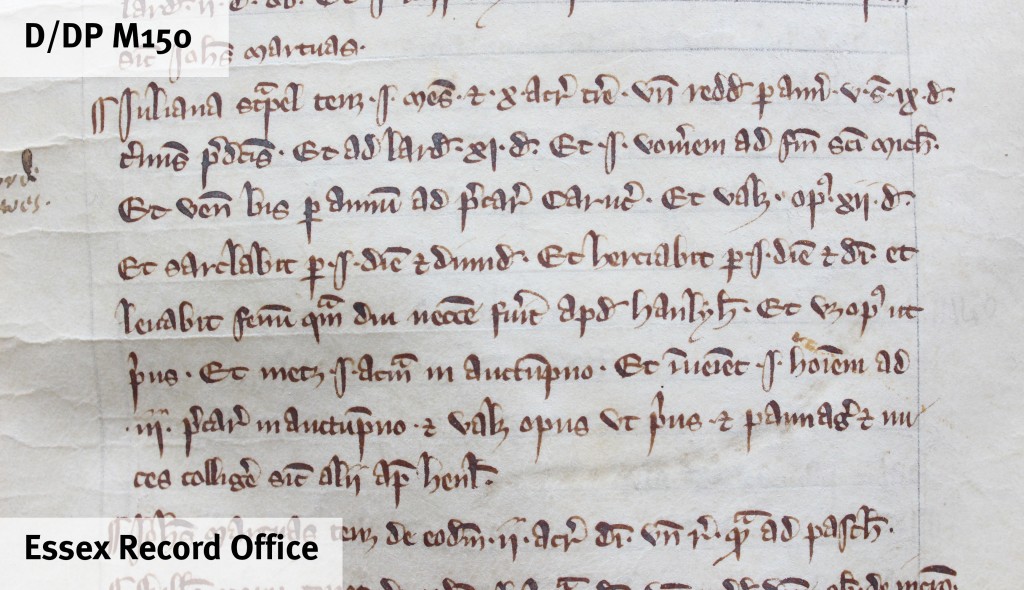

The survey of the manor of Ingatestone of c.1275 (D/DP M150) is stitched into a rental and names the tenants, with a brief description of their holdings and a more detailed list of the service they owed the lord. For the tenants the survey recorded the extent of their liabilities and offered the assurance that the lord could not demand more work from them. This document was known as the ‘Domesday of Barking’ (Barking Abbey owned the manor) and appears as such in a court roll of 1322-1323 where it was produced as evidence in a dispute about a customary fine.

The ‘Domesday of Barking’ records that Juliana Strapel (you can make out her name at the beginning of the first full line shown here) held one messuage and 10 acres. Her obligations from this landholding included the payment of 5s 3d. annually, 9d. ‘lardsilver’ (a payment to the larder of Barking Abbey), and payment of one ploughshare at Michaelmas. She was also obliged to plough twice a year, hoe and harrow each for one and a half days, make hay, reap one acre in the autumn, and provide a man to work for three days. She also owed pannage, where pigs were allowed to roam in the wood to feed off acorns, and was obliged to collect nuts

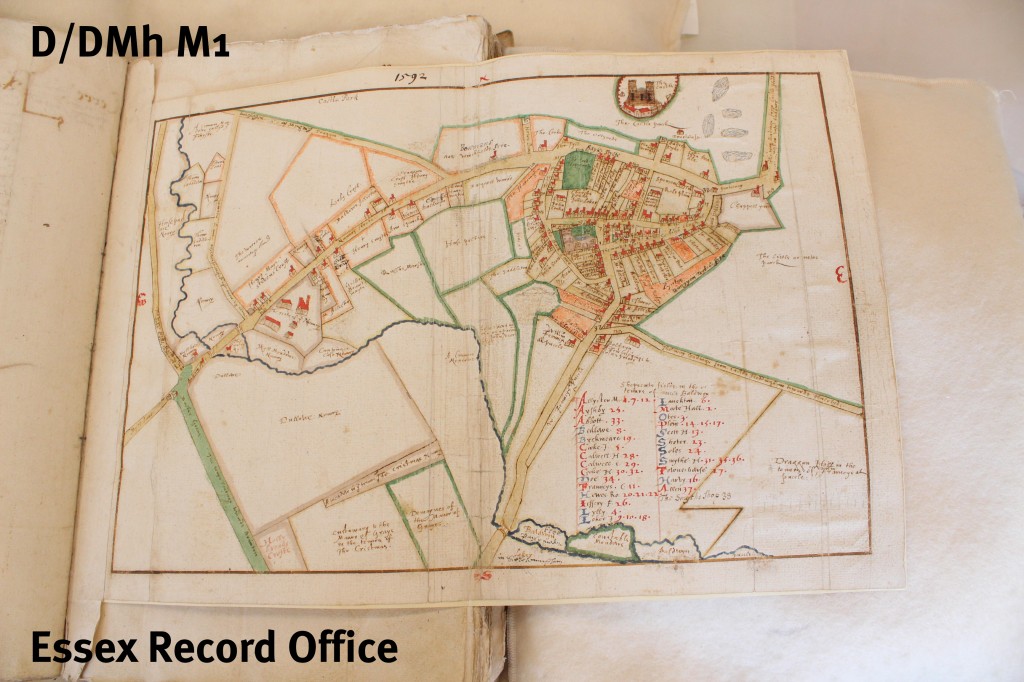

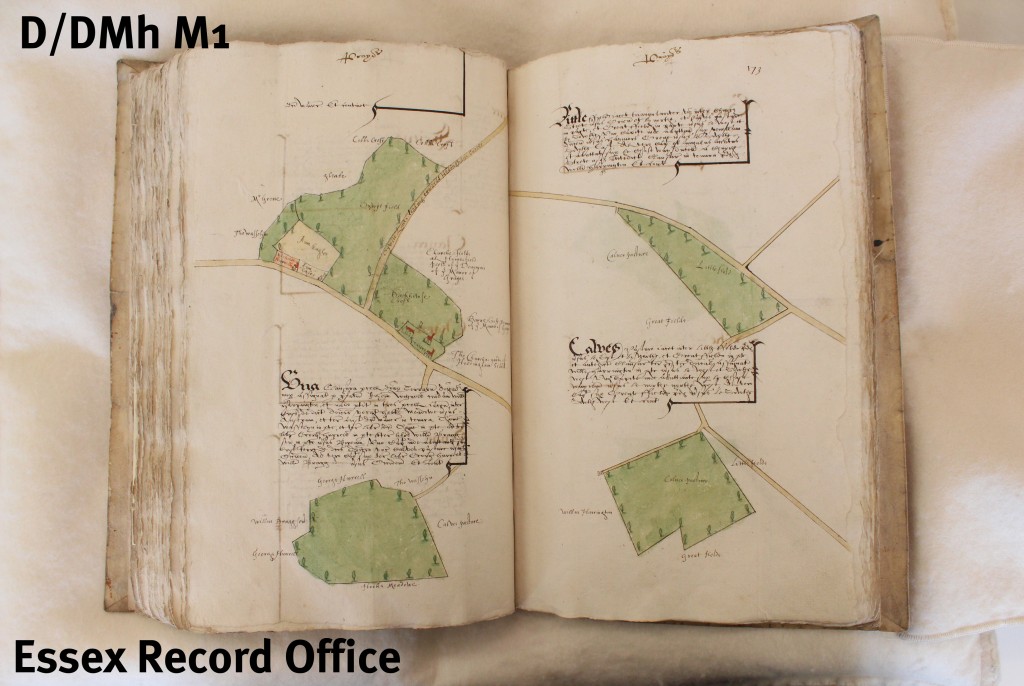

Originally, records dealing with boundaries used written descriptions of the land in question. During the 16th century these written descriptions developed into maps and some of the earliest local maps in the Essex Record Office were produced by manors. In 1592 Israel Amyce produced a written survey of the manor and lordship of Castle Hedingham (D/DMh M1). In order to make the written descriptions clearer he included marginal sketch maps and larger pull-out maps.

Pull-out map of centre pf Castle Hedingham in survey of manor and lordship of Castle Hedingham by Israel Amyce, 1592 (D/DMh M1)

A survey of manor and lordship of Castle Hedingham by Israel Amyce, 1592, using a combination of written descriptions and maps (D/DMh M1)

Maps were costly to produce as it usually required the employment of somebody with the cartographical skills of Amyce or Walker. Terriers and perambulations (where the boundaries were walked) and a written description was produced, continued as a cheaper alternative to describe the bounds of a manor.

Rentals

After the Black Death of 1348-1349 and the estimated loss of between a third and half of the population, lords of the manor found it much more difficult to enforce labour obligations on their tenants. This made it much less profitable for lords of the manor to farm the land themselves and increasingly the lords commuted the labour services into a rent. At Thaxted in 1393 the survey (D/DHu M58) lists all of the labour services which had been due from each tenant and then concludes ‘now pays to farm’. The rent payable quit the tenant of any further labour obligations and from the 15th century onwards rentals or quit rentals are found among manorial records. Rentals name the tenants, and often give a description or even names of the copyhold premises they occupied, with the amount that they owed to lord.

Accounts (compoti)

When lords of the manor farmed the lands of the manor themselves, detailed bailiff’s accounts or compoti (from the Latin computare to calculate or estimate) were produced. The parchment membranes of accounts and rentals are usually stitched together end to end to produce an effect like a giant till roll. When unrolled they can be several feet long.

A compotus usually runs from Michaelmas to Michaelmas and there is a set pattern, beginning with the cash amounts to be charged and then discharged, the corn and stock (in a specified order) and then labour services. The compotus for the manor of Terling, 1328-1330 (D/DU 206/22) is the record kept by the bailiff William Knott. He accounted first for all of the money and goods coming in, including the sale of produce and purchase and birth of livestock. He then continued by listing every charge on the lord’s income including shoeing horses, making wheels, wages for work including ditching the park and roofing and repairing the gutters of the hall, chapel and dovecot. Knott also accounted for every loss of livestock, including deaths from the ‘murrain’ (a catch-all word used to describe unidentifiable animal diseases) and payments of eggs to the lord’s household and to the church. One of the biggest items of expenditure was bringing a watermill from Prittlewell (£10). There were further payments for the mill including digging the pond for it and removing the earth, buying nails and tiles and timber from Boreham and paying a carpenter.

![Extract from the compotus for the manor of Terling, 1328-1330 (D/DU 206/22), which records the purchase of a watermill [molend’ aquatic] from Prittlewell [Priterewelle] to be moved to Terling.](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/D-DU-206-22-Terling-compotus-crop-1024x287.jpg)

Extract from the compotus for the manor of Terling, 1328-1330 (D/DU 206/22), which records the purchase of a watermill [molend’ aquatic] from Prittlewell [Priterewelle] to be moved to Terling.