During our closure due to the Covid-19 pandemic we have been working hard adding new entries to our catalogue “Essex Archives Online“. Archivist Katharine Schofield takes a look at one of these documents which reveals that rights of way disputes aren’t a modern invention.

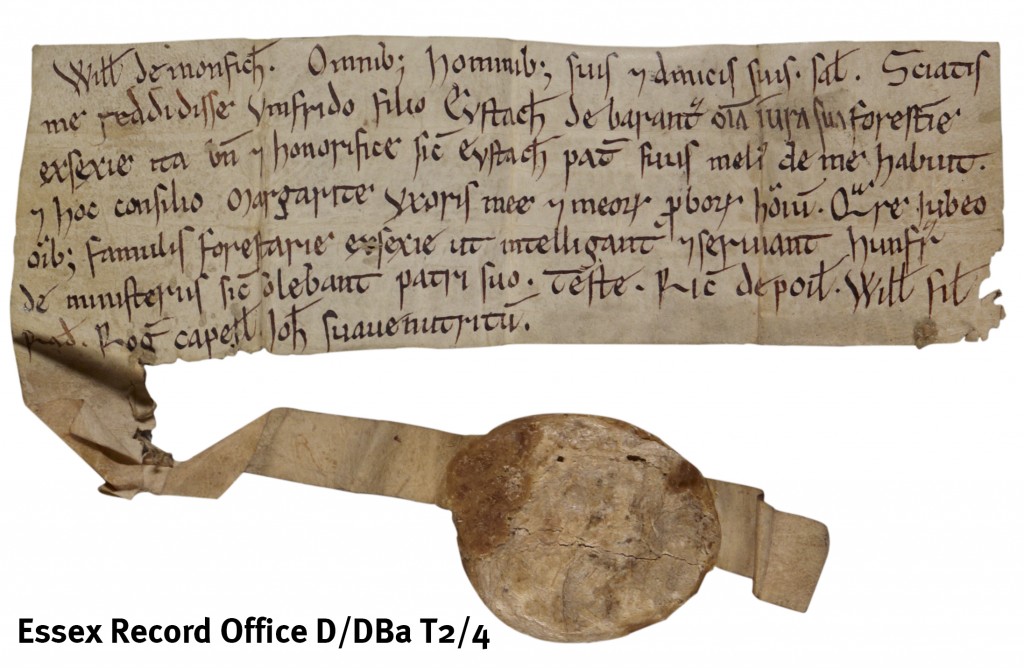

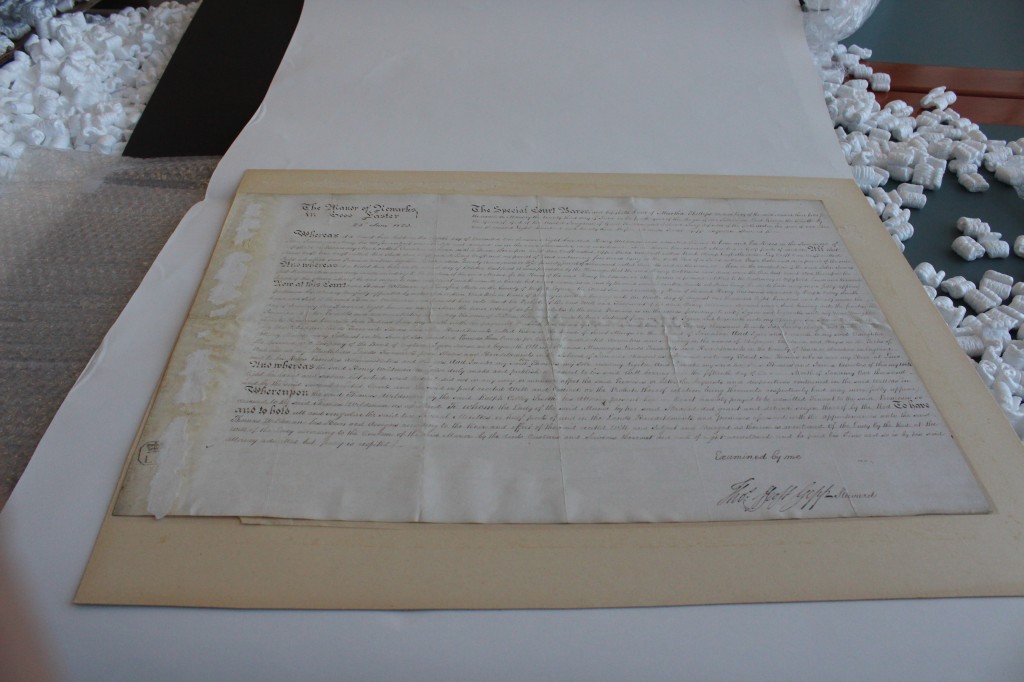

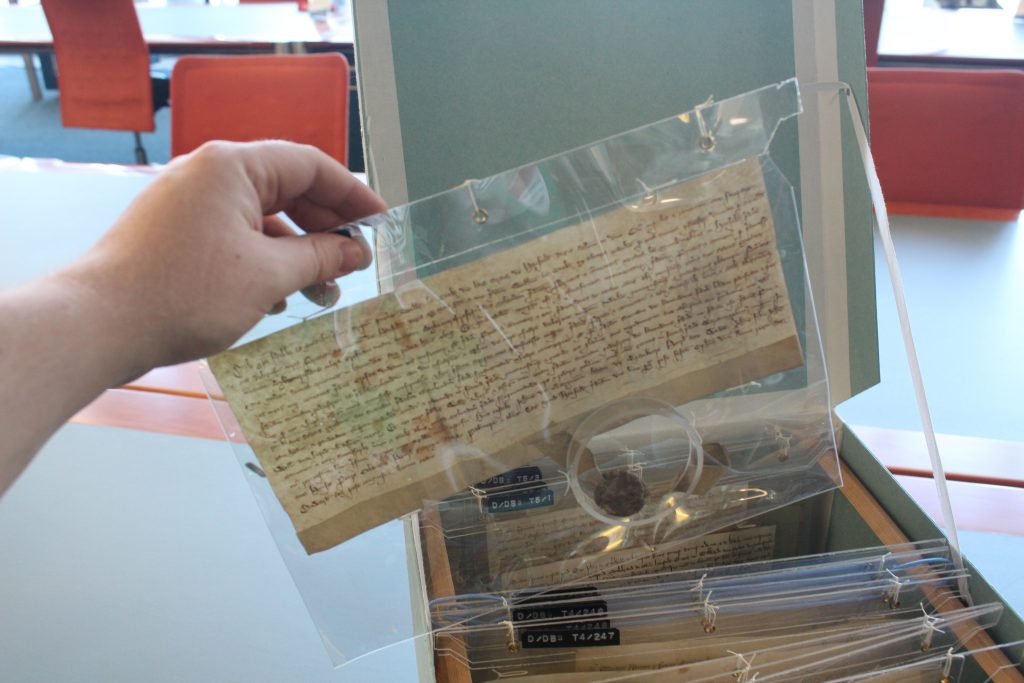

Among the entries added to our online catalogue during ‘lockdown’ are calendars of medieval deeds, dating from the early 13th century onwards, relate to various small properties mostly in Hatfield Broad Oak. The deeds are part of the Barrington collection (D/DBa).

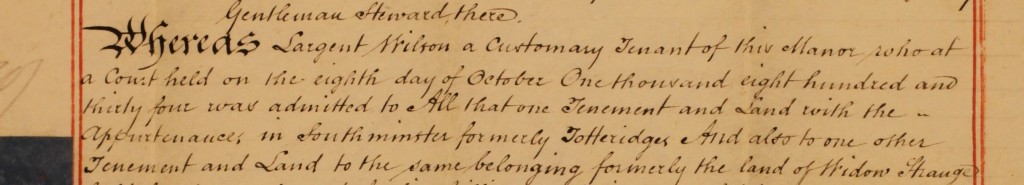

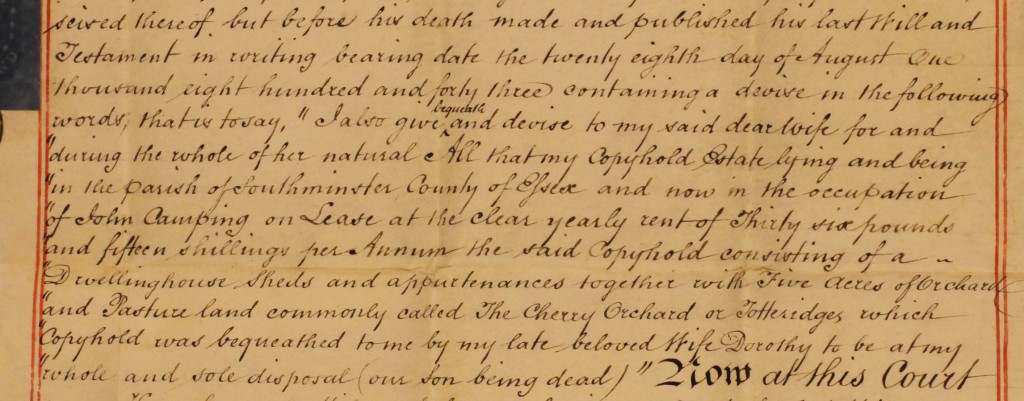

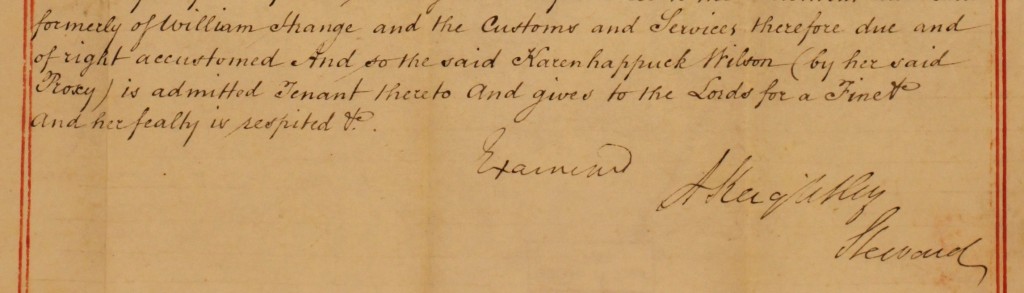

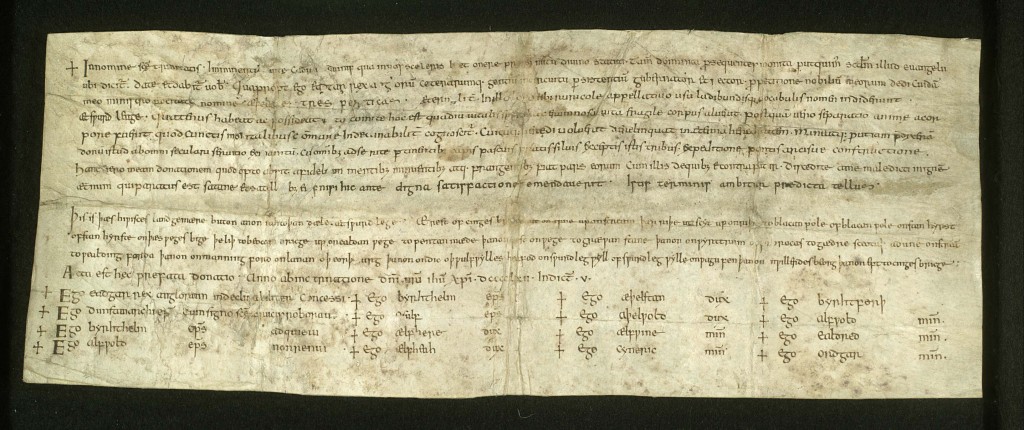

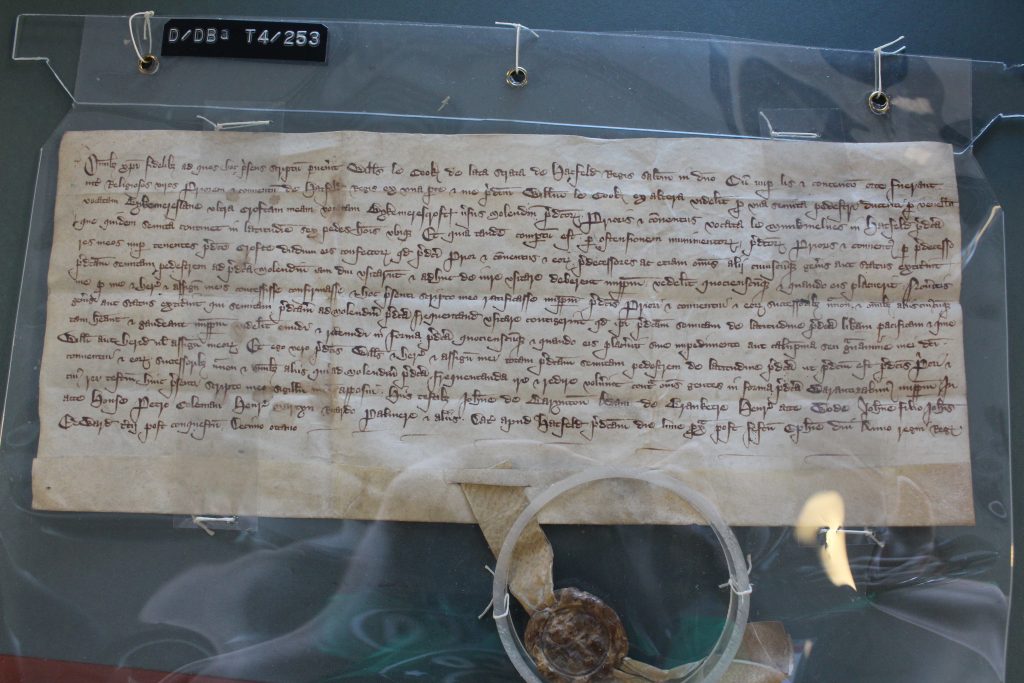

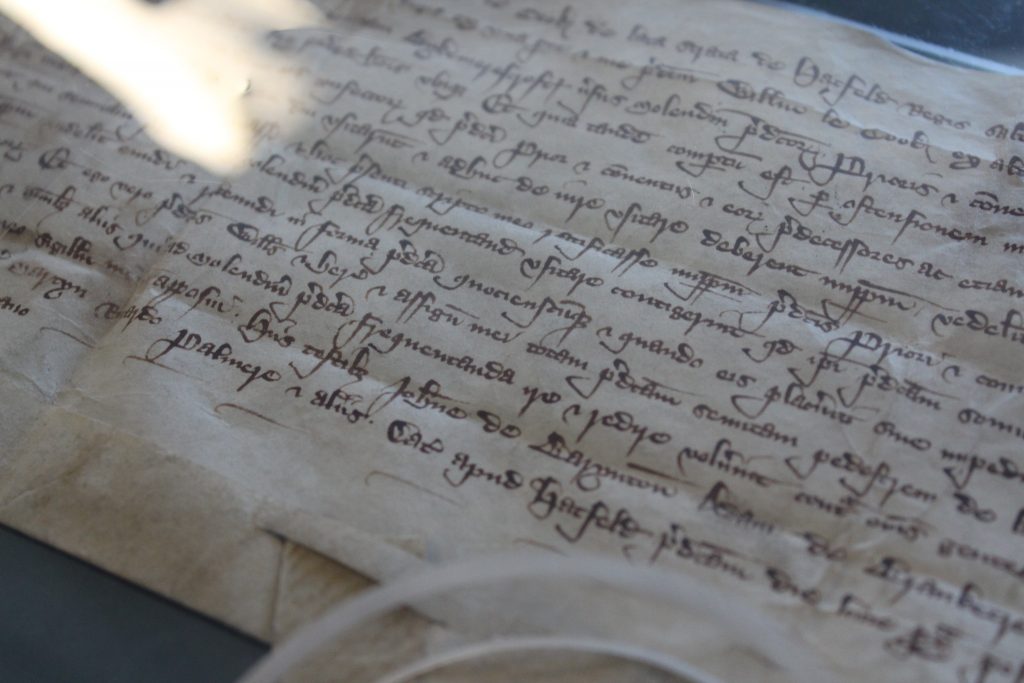

Not all of the calendared deeds related to the Barrington family’s possessions at the time, although they may have subsequently acquired the land. They include the ratification of an agreement (D/DBa T4/253) between William le Cook of Broad Street and Hatfield Priory, dated at Hatfield Broad Oak on the Monday after Epiphany in the 18th year of the reign of Edward III (10 January 1345) and it concerns a dispute over access. John de Barynton’ is listed as the first of the witnesses.

The access in contention is described as a footpath 6 feet wide leading through Bykmereslane beyond William’s property Bykmerescroft towards Munkmelnes where the Priory’s mill was located. Canon Francis Galpin identified Bykemere Street or Lane as the present-day Dunmow Road (B183) past the junction of the High Street and Broad Street (Essex Review volume 44, page 88). He described the name as a corruption of Byg (or big) mere, probably derived from the nearby ponds. The ponds still visible on maps today presumably provided the water power needed for the Priory’s mill.

The agreement recites that there had been ‘contention’ between William and the Priory over the footpath. The Priory produced deeds from their archives (ostensionem munimentorum), made by William’s predecessors, tenants of Bykmerescroft. The archives had demonstrated that the Priory and all others were accustomed to use the footpath to the mill and had the right to do so. Consequently, William agreed to make rectification.

Mills were a vital part of the medieval economy. At the beginning of the 13th century, it has been estimated that there were between 10 and 15,000 mills in England. They were also a key part of the income of a manorial lord. Lords were able to compel their tenants to use their mills, paying for the right to do so. It has been estimated that payments from mills made up 5% of manorial income at the beginning of the 14th century (John Langdon ‘Lordship and Peasant Consumerism in the milling Industry of Early Fourteenth Century England’ Past and Present 145, pages 3-46, November 1994). The Priory was anxious not to have access to their mill disrupted and their record keeping ensured that they were able to prove their rights and request remedy.

Even today, among the many people visiting the Record Office and using the archives, it is not unusual for people to try to solve access problems, although mostly by using Ordnance Survey maps, rather than medieval deeds.