On the night of 23 September 1916 12 Zeppelins crossed the Channel to attack locations around the country. Two of them were to make their final resting places in the fields of Essex, much to the surprise of the locals who found these giant machines descending upon them.

One of the giant airships, the L33, made a forced landing at Little Wigborough and the crew all walked away largely unharmed. The other, the L32, crashed in flames in Great Burstead, killing all on board.

There are many records in our collections which tell the stories of both of the airships coming down, from civilians, Special Constables, Police and the military.

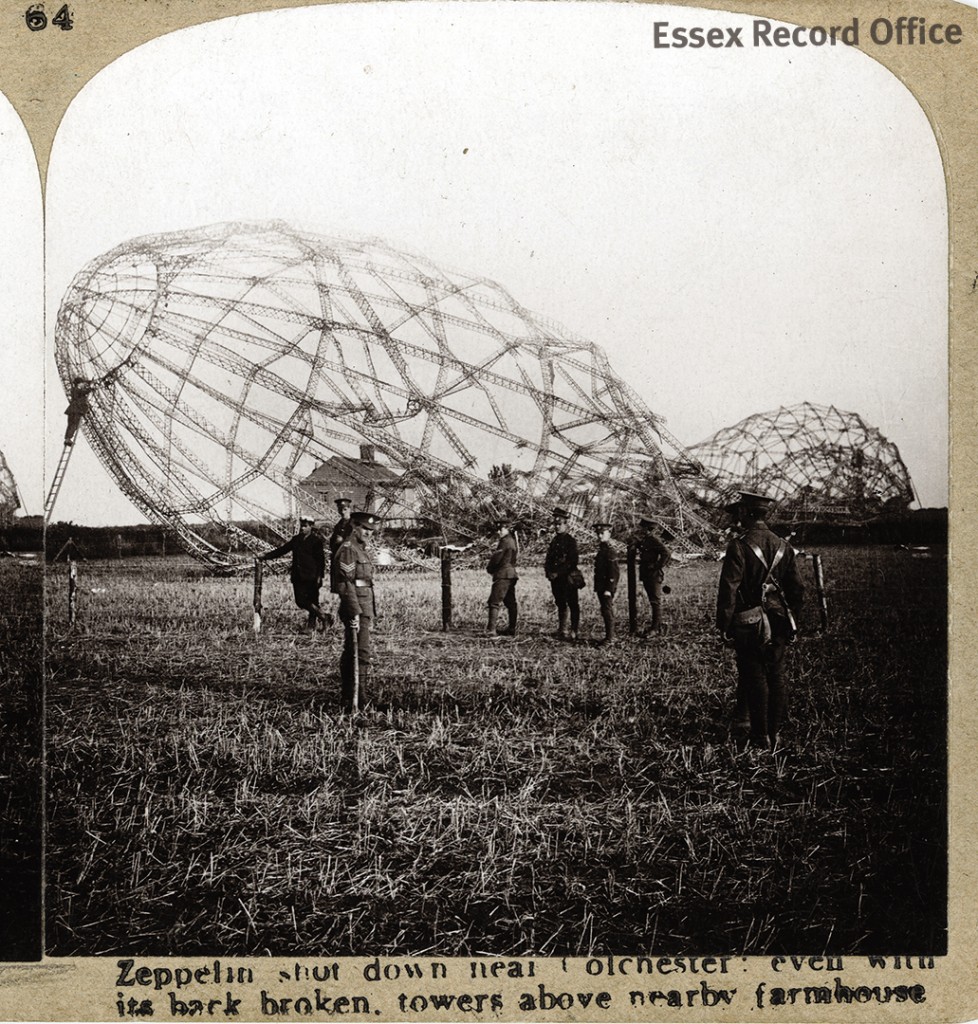

The wreck of Zeppelin L33 at Little Wigborough

The wreck of Zeppelin L33 at Little Wigborough

Why were there Zeppelins over Essex?

Zeppelins were giant airships used by the Germans to drop bombs on Britain during the First World War. They were named after the German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, who pioneered them from 1895. They were filled with hydrogen which is lighter than air, but explosive. They were 650ft long and carried a crew of 22 and a payload of 2 tons of bombs.

Airships flew over Essex attempting to reach London. They crossed the North Sea and flew over the Essex coast, before following the Great Eastern Railway or the River Thames to London. Many never reached their destination because of anti-aircraft guns around the capital, and turned back, dropping their bombs indiscriminately over Essex.

Zeppelin L33 – Little Wigborough

On the night of 23 September 1916 Zeppelin L33 was busy dropping incendiary bombs over Upminster and Bromley-by-Bow when it was hit by an anti-aircraft shell, despite being at an altitude of 4,000m. Its gas bags were punctured by shrapnel and it started to lose height.

By following the railway line, the crew navigated to Chelmsford where they were engaged by Lieut. A de B Brandon of the Royal Flying Corps, but his machine gun fire had no effect.

The ship was losing height and the crew jettisoned everything they could; items were found strewn across the fields over the next few days, including a machine gun, two cases of machine gun cartridges, and maps.

By 1.15 a.m. the ship had reached the coast, but the crew realised they could not make it back across the Channel. The Commander, Kapitanleutenant Bocker, turned the ship inland and brought it down near Little Wigborough, narrowly missing some cottages.

Bocker spoke good English, and he warned the residents of the nearby cottages that the airmen were going to set fire to the airship to prevent it falling into British hands. The Zeppelin was burnt and left as a broken shell, but there was still much in the wreckage that the British could learn from in building their own airships.

The crew then set off to walk to Colchester to give themselves up. They were found on the road by a Special Constable and remained in captivity for the rest of the war.

Eyewitnesses

Records at the Essex Record Office include several eyewitness accounts of the both Zeppelins which came down on the night of 23 September 1916. One of the most detailed accounts of the descent of the L33 is an excited letter written by 40-year-old Rose Luard who lived nearby in Birch. (We have written before about her sister Kate Luard who was a nurse on the Western Front throughout the war.)

In her 6-page description Rose describes the ‘thrilling’ night the L33 landed in Wigborough, with most of the household dashing from window to window to see the drama unfolding a few fields away. On the following day members of the family went to see the wreckage:

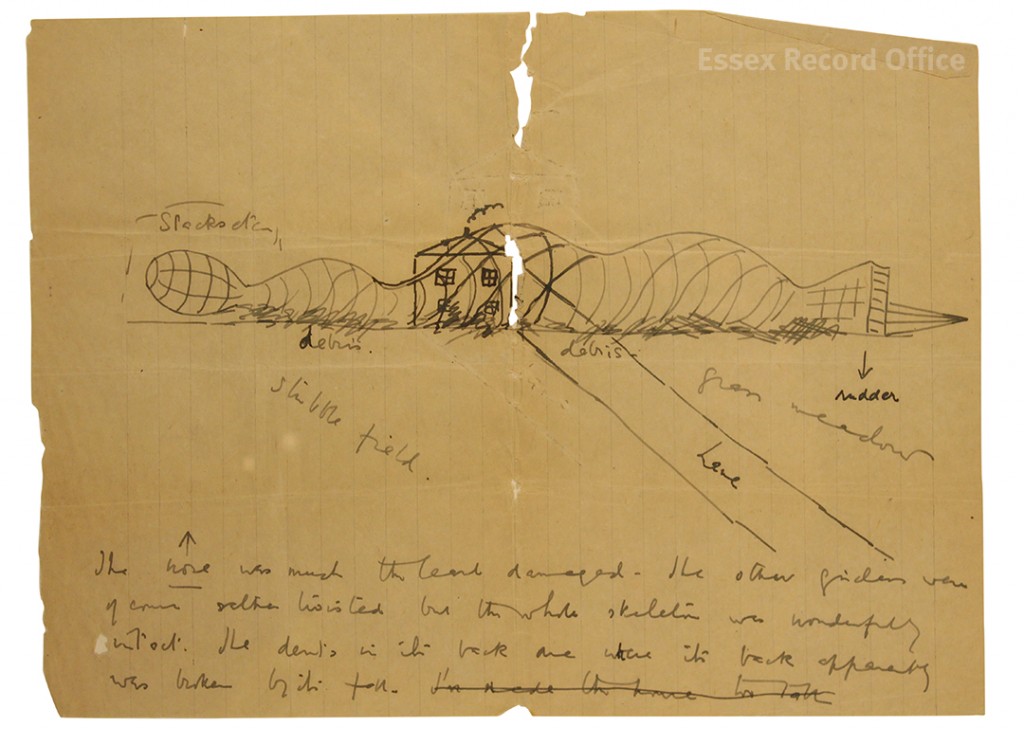

The Zep. is a vast monster, lying in its naked framework of girders, across 2 fields & a land between them. Parts of it look absolutely unhurt, but of course the gas bag is all burnt and the bottom machinery part is all smashed on the ground, & its back is broken & bent in several places, so that it looks like a gigantic antediluvian reptile of sorts, with its nose posed in the air, & its tail intact behind. I tried to make a very rough sketch of its shape as it looked from the stubblefield, which was the nearest we were allowed to go, about a field off.

Her writing is a little tricky to read in places, but still the letter gives us a sense of the sensation the Zeppelin created in the village and surrounding areas; you can read a transcript of her whole letter here.

Rose Luard’s sketch of the wreck of Zeppelin L33 at Little Wigborough, 24 September 1916 (D/DLu 76)

Police reports

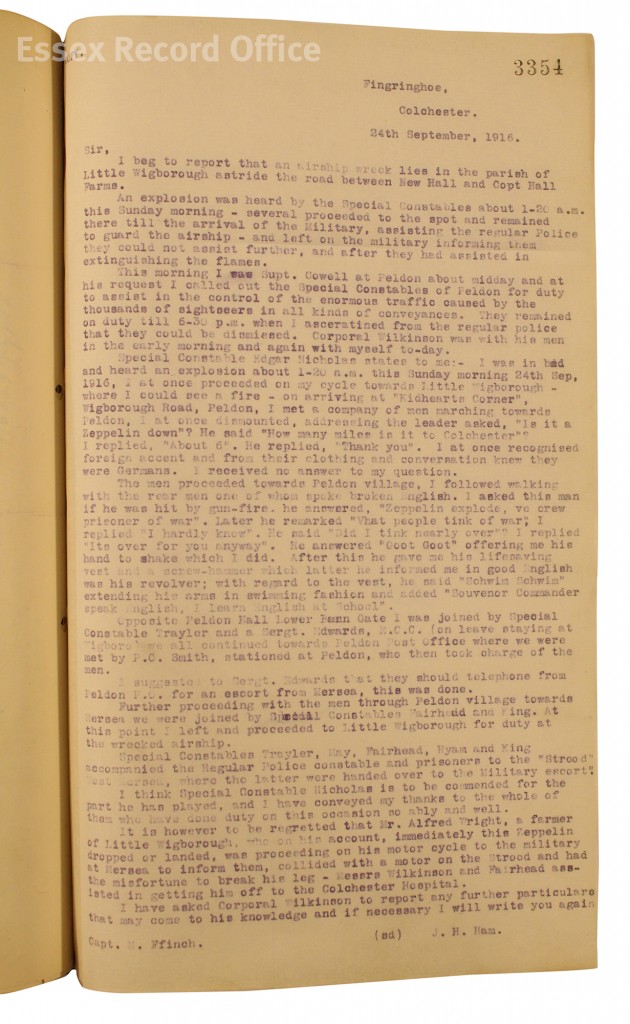

There are several documents written by Police and Special Constables which tell us about what happened on the night of 23 September and in the following days and weeks. This letter from Captain M Ffinch reports on how the Special Constables of Peldon helped to control the traffic and sightseers which descended on the village on day after the Zeppelin landed. It also includes a report from Special Constable Edgar Nicholas, who was the first local man to encounter the German crew.

Nicholas described being in bed and hearing an explosion at about 1.20am. He got up and set off on his bicycle towards Little Wigborough, where he could see a fire. Before he reached the site of the wreck he came across the German crew who were trying to find their way to Colchester to hand themselves in. Nicholas followed them to Peldon village, talking to those in the crew who spoke English. One of the Germans asked him what English people thought about the war, and shook Nicholas’s hand. The party soon encountered other Special Constables and the crew was handed over to PC Charles Smith at Peldon, who telephoned the army to come and fetch the crew to take them prisoner.

Report from Capt M Ffinch on the activities of the Peldon Special Constables on the surprise arrival of L33 (J/P 12/7)

Zeppelin L32 – Great Burstead

While the L33 was making its forced landing in Little Wigborough, the L32 had bigger problems.

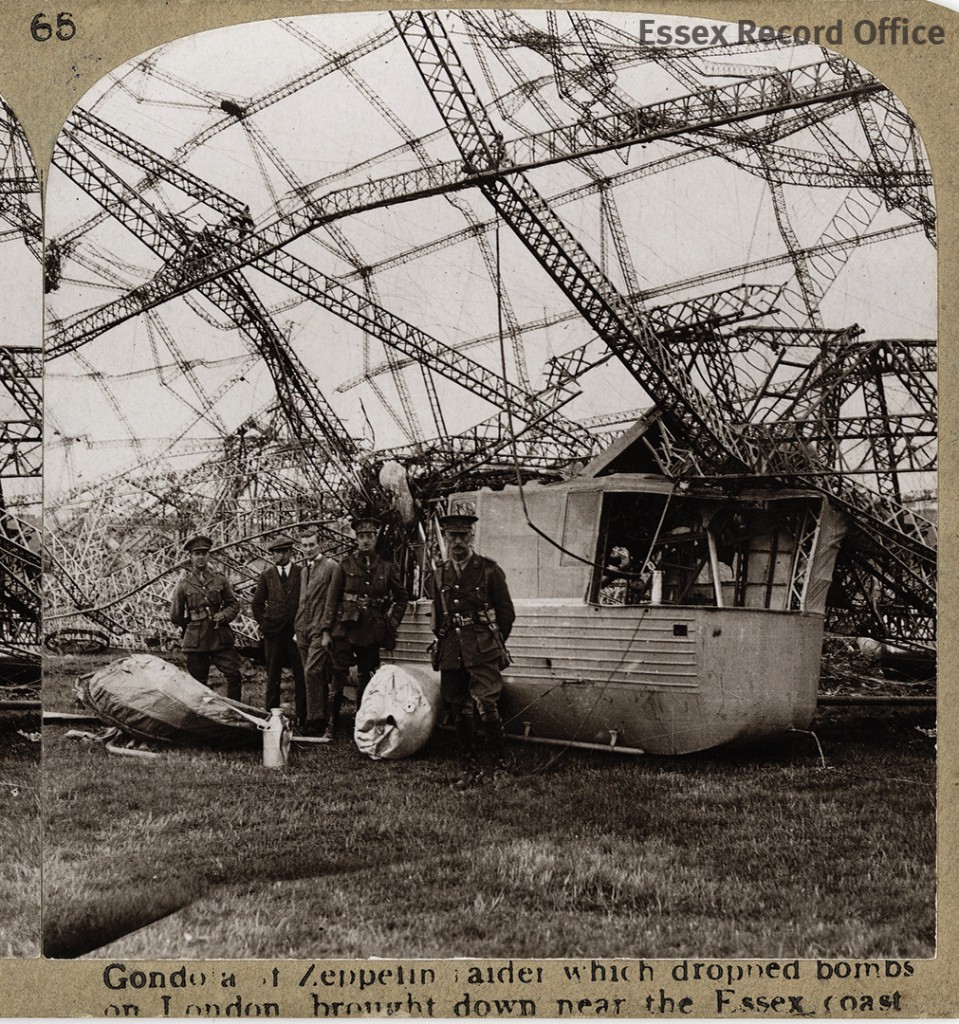

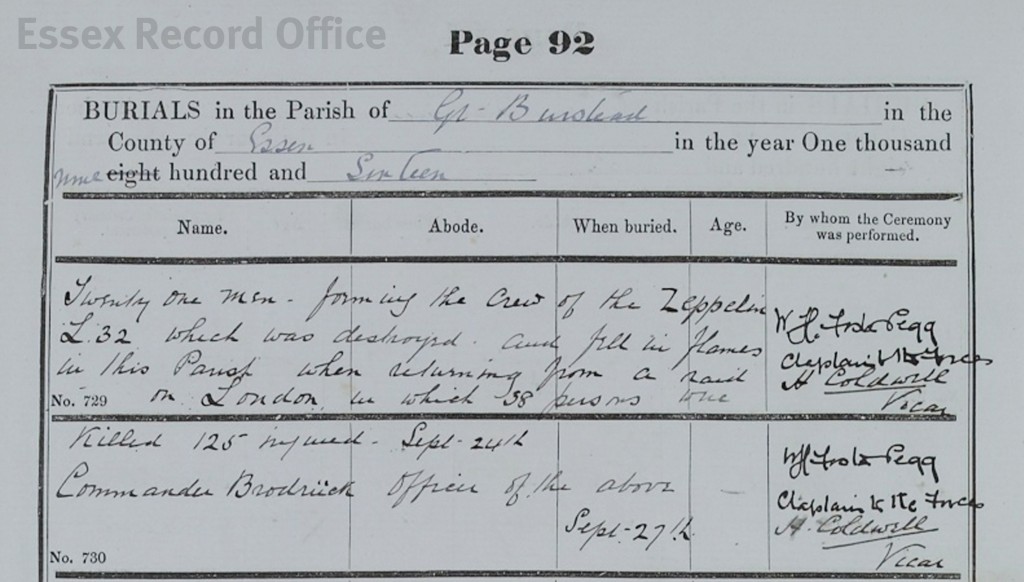

It had dropped its bombs in Kent before flying north over Essex. It was spotted by a BE2c flown by 2nd Lieut. Frederick Sowrey, who hit the airship with incendiary bullets which set it alight. The L32 came down in flames near Great Burstead. The entire crew of 22 men was killed.

The following day, just as at Wigborough, the wreck site became a tourist attraction. Catherine Brown, who worked at the Kynochtown munitions factory at Corringham, later recalled:

The next morning, some of the girls who lived that way went to view the wreck. They also saw some of the poor lads who had been shot down; they only looked about 16 years. We could not help but feel for their mothers in Germany.

Sgt James McDiamid was stationed nearby with the Glasgow Yeomanry, who were despatched to help guard the wreck. On Monday 25 September he wrote to his brother Hugh giving his perspective on events:

Well, yesterday morning at 7a.m. we were sitting at breakfast when the adjutant came in and told us to be ready as soon as possible full marching orders – that is horses and men with everything on. The first twenty who were ready were sent off with Lieut. Young (I was one of them) to where the wrecked Zepp was. We had ten miles to go and we travelled hard. There was a mark along the road of the sweat off the horses. We trotted every step of that ten miles. We picketed our horses, left three men to guard them, and fixed bayonets and down about 20 yds to where the heap of wreckage was lying. We had to keep the people back form it. Everybody wanted a souvenir & most of them got it too. There must have been an explosion after she landed for there were bits found a mile away.

The heap of twisted bars of alliminimum [sic] was about 40 ft high. A tremendous pile, unless you saw it you would hardly credit it. Then the work of pulling out the bodies commenced. It was a gruesome job. The R.A.M.C. and the R Flying Corps did that. They got twenty two bodies. The commander was not badly smashed but some of the others were in an awful mess.

The crewmen were buried in Great Burstead churchyard. Their bodies were later moved to Cannock Chase.

Burial of the crew of L32 at Great Burstead (D/P 139/1/23)

Sightseeing and souvenirs

The following day, both sites were abuzz with sightseers. Rose Luard described the scene at Wigborough:

A dazzling day & a very happy heterogeneous crowd of country people, mixed with Colchester of course, all taking their Sunday matins in that pleasant form. A good many soldiers and officers of course from Colchester, with their womenfolk & I saw one old General & lots of red tabs prancing [?] about on the stubble with the common herd. It was Fred & I who swelled the godless crowd. I persuaded him to come with my in the morning. Daisy & Nettie have gone this afternoon, but I expect the few hundreds will have swelled to thousands this afternoon. It was such a jolly local crowd, gazing at their own Zeppelin, none of y[ou]r hoards from London.

Special Constables, Police and the military were deployed to control the crowds. Sgt McDiamid told his brother:

The crowds were immense during the day but very orderly, altho’ quite annoyed at not getting closer. During the day there were six British aeroplanes and a British airship came along to see the wreckage. One of the aeroplanes landed not twenty yards from where I was standing.

Capt. M Ffinch sent the Special Constables of Peldon out ‘to assist in the control of the enormous traffic caused by the thousands of sightseers in all kinds of conveyances’.

Many of these sightseers wanted a little piece of Zeppelin of their own as a souvenir of their unusual experience, which caused an even greater problem for those tasked with guarding the wrecks.

The wrecks were considered to be of military importance, and punishments for anyone found with anything taken from the wreck sites were severe – a fine of £100 or imprisonment with hard labour for six months.

Despite the warnings, many people still collected and kept fragments of wreckage or other items – including, it seems, police and the military themselves. Rose Luard described:

Our Policemen got near & picked up a bit of the burnt gas bag covering and gave it to George whom I met on the field & he gave a bit to me. It is very fine canvas with a silky sheen on it.

Sgt McDiamid told his brother:

I got a lot of wee bits of Zepp but we were not supposed to take them away altho’ there wasn’t a man there who hadn’t a bit. This is a piece of it I picked up near it. The cloth is a piece of the commanders [sic] clothing.

Two fragments reputed to be from Zeppelin L33 which have been made into pendants (M55, M56)

Even though this is one of our longer blog posts there is still plenty of material in the archive which we have not had space to mention. If you would like to know more, we recommend The Impact of Catastrophe by Paul Rusiecki which is available to read or buy at ERO (£17 + P&P – call us on 033301 32500) or to borrow from Essex Libraries. If you would like to go straight to the primary sources themselves, why not have a search on Essex Archives Online to discover what other stories our archives hold.

Even though this is one of our longer blog posts there is still plenty of material in the archive which we have not had space to mention. If you would like to know more, we recommend The Impact of Catastrophe by Paul Rusiecki which is available to read or buy at ERO (£17 + P&P – call us on 033301 32500) or to borrow from Essex Libraries. If you would like to go straight to the primary sources themselves, why not have a search on Essex Archives Online to discover what other stories our archives hold.

_________________________________________________________________

On Saturday 24 and Sunday 25 2016 the village of Little Wigborough is holding Zepfest to mark the centenary of the landing of L33 in their parish. There will be a small display from ERO in St Nicholas’s church, and there are activities taking place all weekend.