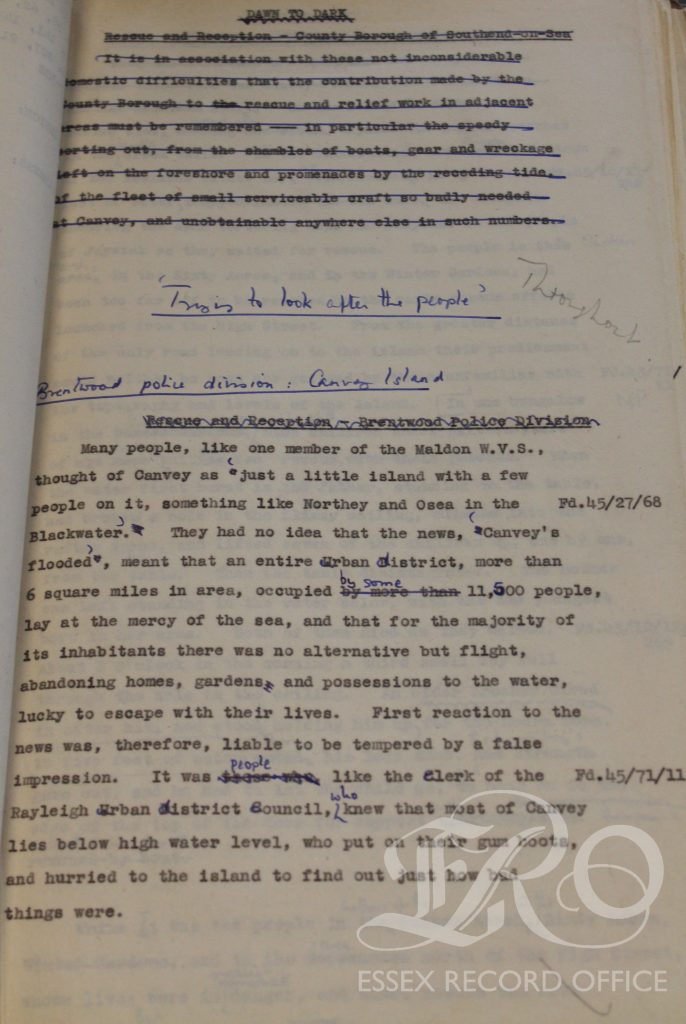

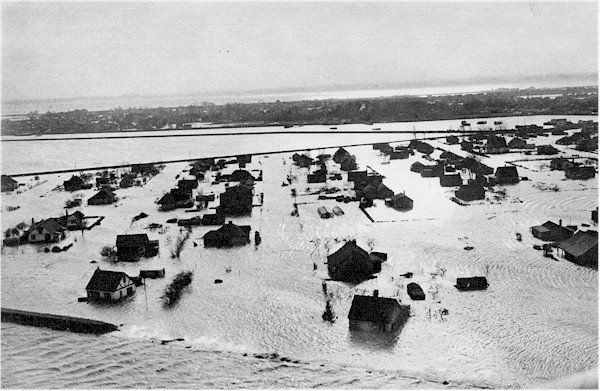

As described in our earlier blog post, this week marks the 70th anniversary of the 1953 North Sea flood, one of Europe’s worst peacetime disasters in the the twentieth century. As communities along the Essex coast gather to commemorate the lives lost, amongst them will be people who still remember the devastation caused by the flood, although most were just children at the time. But how will we remember the flood when it fades from living memory?

At the ERO, we are fortunate that the voices of many of those who experienced the flood are now preserved in the Essex Sound and Video Archive. The quote above comes from a recording of Mrs Rudge, interviewed a few days after the flood by Sir Bernard Braine, Canvey Island’s MP. In the recording, Mrs Rudge recalls waking up in the small hours of Sunday morning to find her bungalow in Newlands overwhelmed with water, after the tidal surge overcame the sea wall at Small Gains Creek. Nearly 80 at the time, she spent three days trapped on her dining table before being rescued, without being able to access even the “nice little bottle of whiskey” in her dressing table drawer:

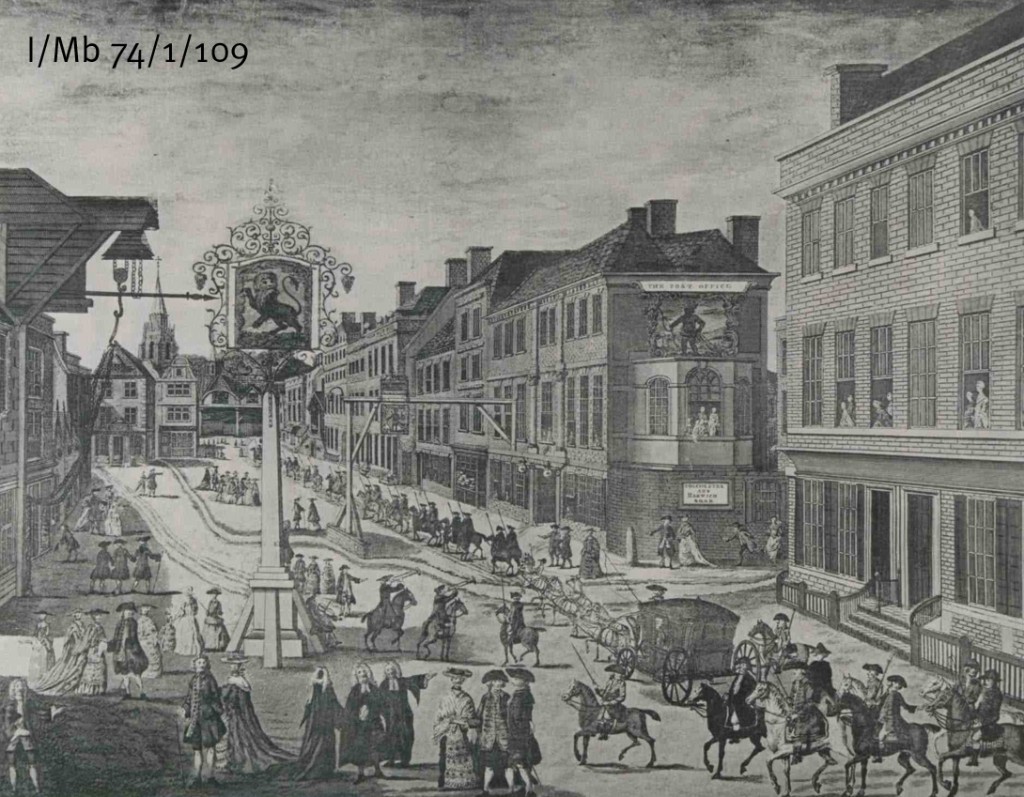

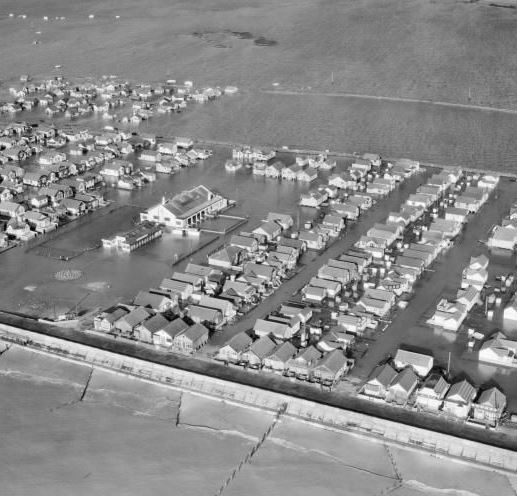

An aerial photograph of Canvey Island during the flood

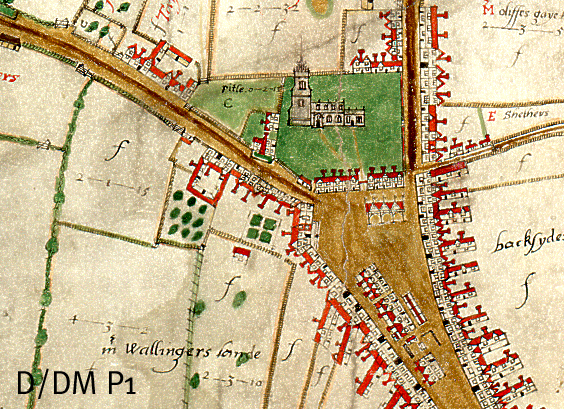

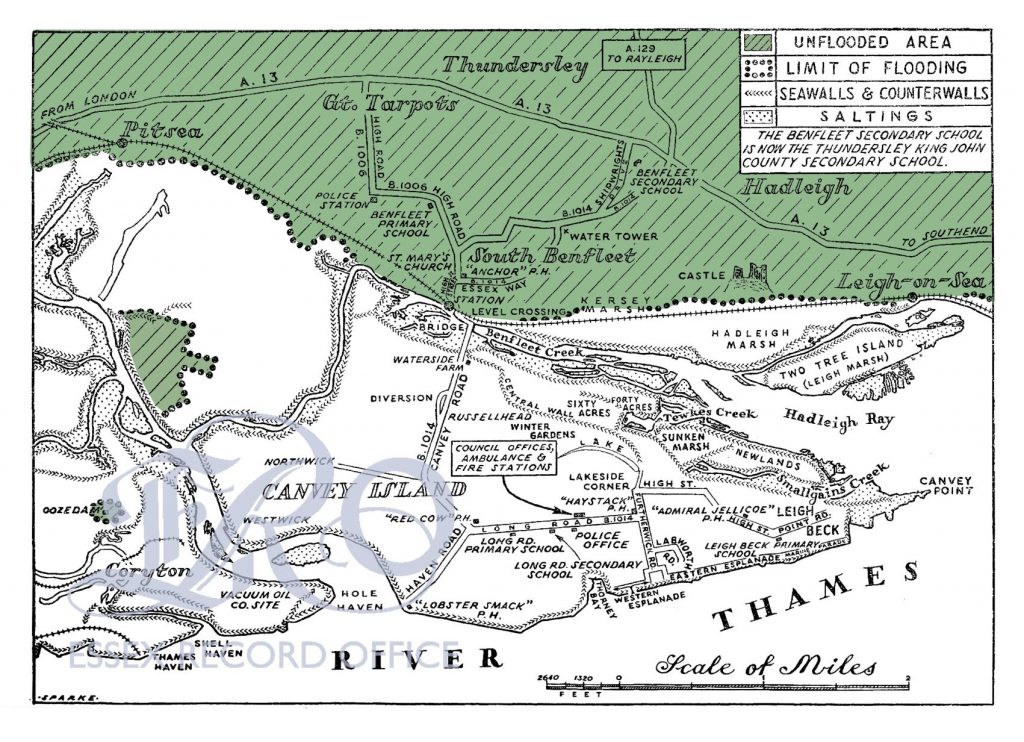

A map of Canvey Island drawn by P.A. Sparke for Hilda Grieve’s The Great Tide

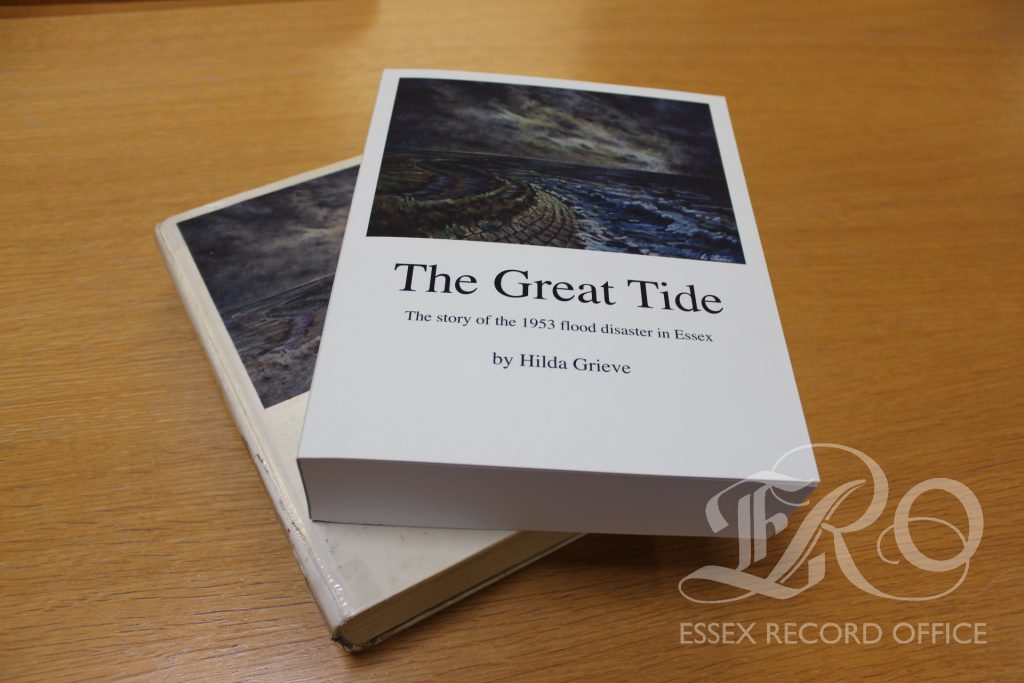

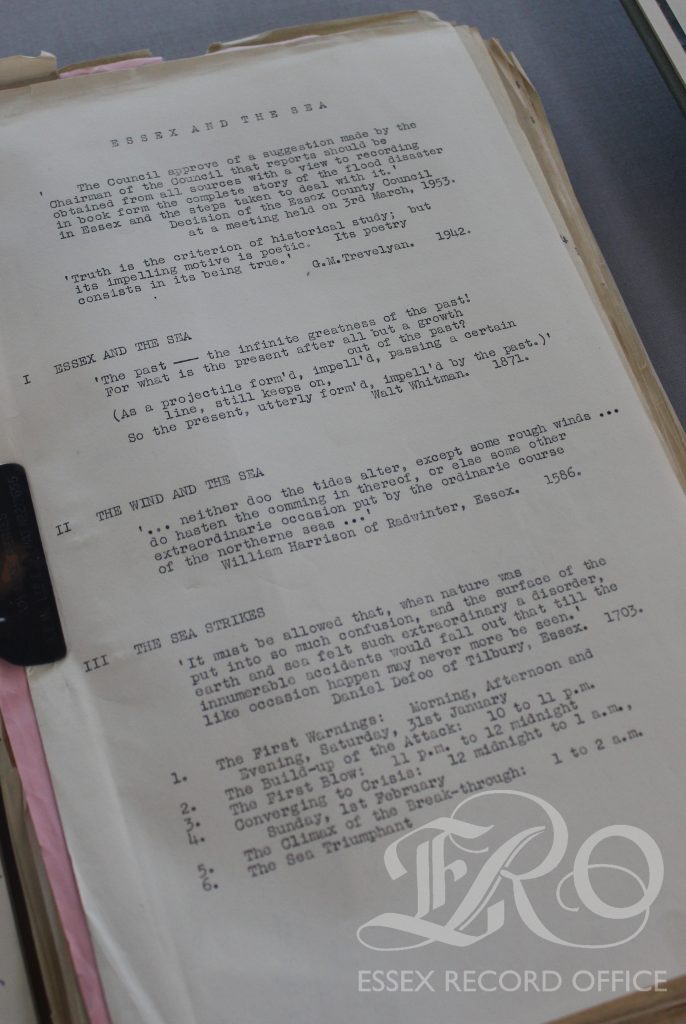

The interview with Mrs Rudge is one of a precious few recordings we hold from the immediate aftermath of the flood. In the decades since, oral historians, community archives, and radio producers have continued to preserve people’s memories of that night, complementing the abundance of personal testimony woven through Hilda Grieve’s The Great Tide. To mark the 70th anniversary, we wanted to share some of those recordings, telling the story of the flood through the words of those who were there.

Rising tides

Interviews with people who had to escape their homes often begin with the moment they realised that they were flooded. As the tidal surge came with very little warning, in the middle of the night, many recall being woken up by the sound of the water in and around their homes. Interviewed in 1988, Audrey Frost described hearing:

“The sound of all this rushing water, it sounded like. And I just sort of tapped Derek, and I said, ‘Sounds as though we’ve got an awful lot of rain coming down.’ And with that he said, ‘My god, it ain’t rain – the sea’s come over!”

Audrey and her husband Derek lived on Gorse Way, one of the worst affected areas of Jaywick. Although it initially seemed that the sea walls had protected most of the town, the tide had breached the wall at Colne Point and swept across the marshes, surging into Jaywick from behind just before 2 AM. By the time that Audrey and Derek realised what was happening, the water was higher than the gutters of their bungalow. Thankfully, they managed to swim out of one of their windows with their eighteen month-old son, Michael, and spent the night on their roof in bitingly cold conditions before being rescued the following morning.

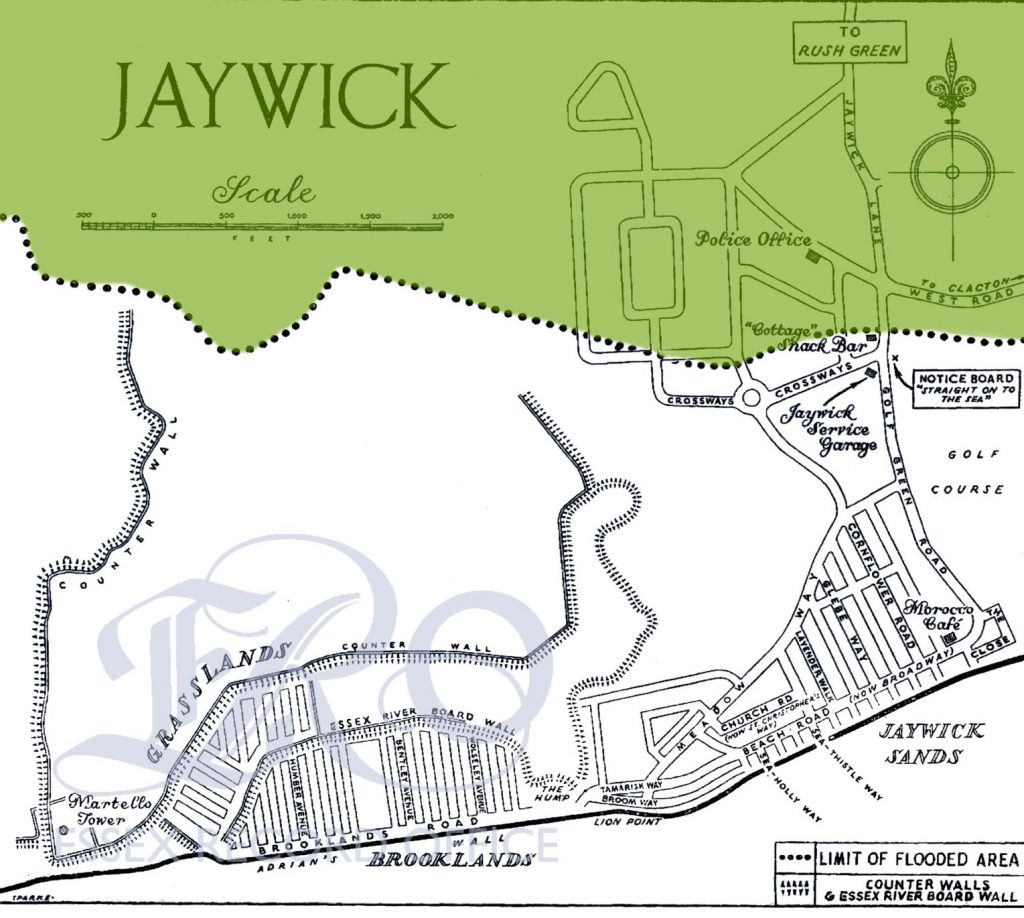

A map of flooding in Jaywick drawn by P.A. Sparke for Hilda Grieve’s The Great Tide

An aerial photograph of the Brooklands area of Jaywick

Like Audrey and Derek, many people in Jaywick and Canvey Island lived in bungalows, making it difficult to get above the freezing water that poured in through their letterboxes and window frames. A common theme in the interviews is the speed at which the water rose, leaving people no time to get dressed or gather possessions. Those who couldn’t make it up to their roofs climbed into their lofts, or – like Mrs Rudge – even onto their furniture as it floated on the water.

One unexpected detail mentioned by many of the interviewees was the challenge posed by lino flooring as it floated up on top of the water and became near-impossible to cross, jamming doors and windows shut. Interviewed in 1993 for the Breeze FM documentary, ‘The Great Tide’, Bill Rowland recalls trying to rescue his son’s brand-new bike at home in Parkeston Quay, Harwich:

“In those days I had a lino runner down my hall, and unthinkedly I came down the stairs, and I could see this bike standing sort of submerged in water. And I could also see the lino runner. And like a silly man, I trod on the lino, and of course, you can imagine, I did a complete somersault, because the lino was just resting on the top of the water. And I finished up in this absolutely icy water. Frozen to the bone I was.”

While some had no option but to stay put and wait for help, others made the difficult decision to try and get through the water to safety. On Canvey Island, Thelma and Donald Payne found that they couldn’t get up into the loft as a gas pipe had been laid across the hatch – and, being seven months pregnant, Thelma couldn’t fit either side of it. Although they found a temporary refuge in the external staircase of the house next door, when Thelma started having pains, they decided to make a break for it in their bath.

Others were lucky enough to have boats that hadn’t been carried away by the flood. In this interview from 2019, Malcolm MacGregor described how he managed to row his family away from their farm in Lee-over-Sands, with his sister’s Exmoor pony swimming behind them. Many of those who had their own boats, like Malcolm, were the first to help their neighbours, rescuing people from their lofts and roofs through the night.

The rescue effort

Co-ordinated rescue efforts varied across the county. The policeman Kenneth Alston arrived in Harwich at 2.30 AM, five hours after the harbourmaster raised the alarm. In the intervening time the tidal surge had inundated the town, cutting it off completely. Interviewed in 1990, Ken recalled that:

“Although the water ran over the quay, the break came from the marshes at the back, what we call Bathside. There were just earthen ramparts. Those ramparts broke and water just poured into the back of Harwich. Overwhelmed all the properties there, the schools, over the railway, into the street behind the police station. And there were panic stations I can tell you.”

While the police and the fire brigade did all they could to help people get up above the water, into the upper storeys of buildings, Ken set about getting in touch with local boat owners and fishermen, the naval training ship HMS Ganges and Trinity House, who all contributed their boats to the rescue effort the following day, when hundreds of people were evacuated out of first and second-story windows.

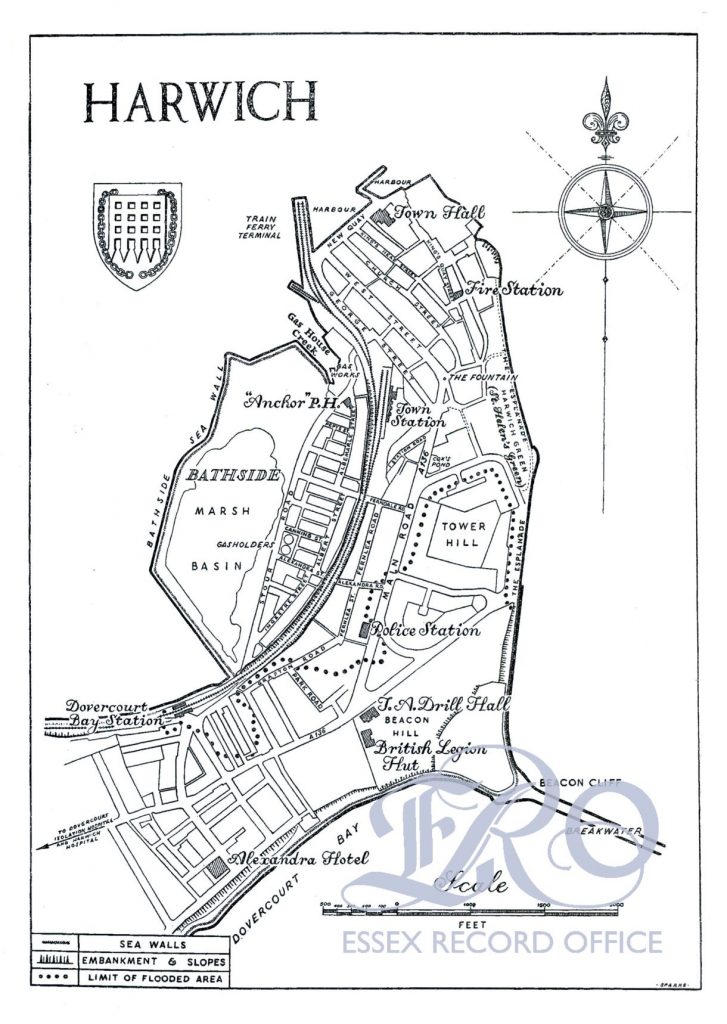

A map of Harwich drawn by P.A. Sparke for Hilda Grieve’s The Great Tide

A photograph of rescue efforts on Albert Street, Harwich

In Jaywick, the force of the water that surged across the marshes washed away the only police car with radio equipment, hampering rescue efforts. PC Don Harmer – who hadn’t even been to Jaywick before – crawled a mile along the sea wall through the flood water to telephone for help from Clacton. Astoundingly, once he’d delivered his report, he followed orders to crawl all the way back again.

Any available boats along the coastline arrived to help as the morning went on, manned by emergency services, fishermen, and local residents. The following day, Monday 2nd February, the BBC journalist Max Robertson talked to some of those who had been involved, who were accompanied by a cat they’d rescued:

“Well we first pushed off from Grasslands in the boat. We hadn’t been rowing many yards when we heard a woman calling for help. So we immediately made for this bungalow, and reassured her that help was on the way.”

Down on Canvey Island, Reg Stevens, Canvey Urban Council’s Engineer and Surveyor, started co-ordinating the rescue effort at around 1.25 AM, when it was clear that the sea walls would not hold. Stevens tried to warn residents using the wartime air raid sirens and sent the policemen and firemen on the island out to reach as many people as they could. As Stevens recalls, the “heroic” telephone operator stayed sitting in the floodwater until his equipment ceased to function. Fortunately, one of the ambulances on the island had been fitted with a radio the previous week, and they managed to get a message out to their MP, Bernard Braine, who helped with the rescue effort from the mainland.

As Canvey remained cut off, the rescuers had to make do with whatever they could find. Geoff Barsby, one of eight part-time firemen on Canvey at the time, recalls using collapsible canvas dinghies to help rescue people from their homes, and then a boat from Peter Pan’s Playground in Southend.

More boats from Southend, Grays, Tilbury and Thurrock arrived as the morning went on, and by 5.30 AM the army and RAF had arrived to help. Thirty-five years later, one of the borough policemen recalled arriving on Canvey early that morning:

“The thing that we noticed as soon as we got out of the van were the cries of help from people who were stranded nearby, plus the noise of the wind, and you know, the shock of seeing so much water in a residential area.”

Many of those involved in the rescue effort recount the practical difficulties of rescuing people. A common theme was the impossibility of using motor boats when there were so many obstacles under the water, forcing rescuers to row. Even that wasn’t straightforward – one interviewee who went out to rescue people from Canewdon and Foulness Island commented that:

“We hadn’t realised that there were so many underwater obstructions, because every now and then there were these ominous bangs coming from underneath the boat. We’d probably hit some farm machinery or a tree or a hedge or something like that and I thought any moment now we’re going to have a hole in our boat and we shall all be sunk.”

Another challenge was getting people off their roofs into the boats. In addition to the strength of the tide, there was always the risk that people would miss altogether, capsize the boat, or in the case of the canvas boats, go straight through the bottom. In one interview, Sammy Sampson describes how he rescued several residents of Great Wakering by encouraging them to slide down his back into the boat.

Once on dry land, survivors were taken to rest centres, co-ordinated by the WVS (Women’s Voluntary Services) and the local chapters of the British Legion, amongst others. As one interviewee recalls, rescued residents of Canewdon, Foulness Island, and Wallasea Island were taken to the Corinthian Yacht Club in Burnham-on-Crouch to be given tea and support. As many of those who escaped were still in their cold, wet nightclothes, the rest centres also co-ordinated collecting and distributing clothing.

On Canvey, those who had escaped their homes initially gathered at William Read School. With the arrival of army lorries, they were taken onto the mainland and to South Benfleet School. By midday on the 1st February, journalists and photographers had started to turn up to document the ongoing rescue effort. One of the most publicised photographs at the time shows PC Bill Pilgrim carrying a child onto a lorry. As he recalls in this interview from 1988, he was just doing his job:

The rescue effort went on for days. Families were scattered across hospitals, rest centres, relatives and friends. Canvey resident Shirley Thomas (née Hollingbury) recalled becoming separated from her parents after her mother was taken to hospital:

“Being twelve years old, I had not noticed that everybody was writing their names on the paintboard in the schools that they were taken to, and I hadn’t done it. So for a couple of days my father hunted in vain for his two girls… Eventually somebody in Benfleet remembered seeing two little girls. Luckily my sister was a redhead, so it had stuck in their mind… And I can still remember my father crying– I never saw him cry again, in his lifetime.”

Despite the disruption, businesses like Jones Stores continued to operate. Interviewed by Ted Haley in 1983, Albert Jones recalls the support of the army and Southend Grocers Association in keeping them going. In the following weeks, residents slowly returned – under the watchful eye of the police, to ensure that looting didn’t take place – to see what was left of their homes.

Many had lost everything to the flood. Yet, alongside the loss, people also recall the generosity of their communities and people across the country who donated clothes, food, and furniture to help the survivors rebuild their lives. There was much press coverage of the attempts to rescue pets and reunite them with their owners, led by the PDSA. One interviewee, Alan Whitcomb, recalled how he was reunited with his tortoiseshell cat after seeing him on the television:

Another interviewee, Winnie Capser, received an RSPCA award for Gallantry and Services on Behalf of Animals for her work. Interviewed in the early 1980s by radio producer Dennis Rookard, she commented that:

“You know, you just can’t imagine it. But I always say now, if you lived through the flood, you could live through anything.”

While it might be difficult for us to imagine the flood, seventy years on, hearing the voices of the people who lived through it – their intonation and emotional cadence – brings the scale of the tragedy closer. In listening to the detail, we bear witness to the human cost of that night – and the human perseverance and courage.

Further listening

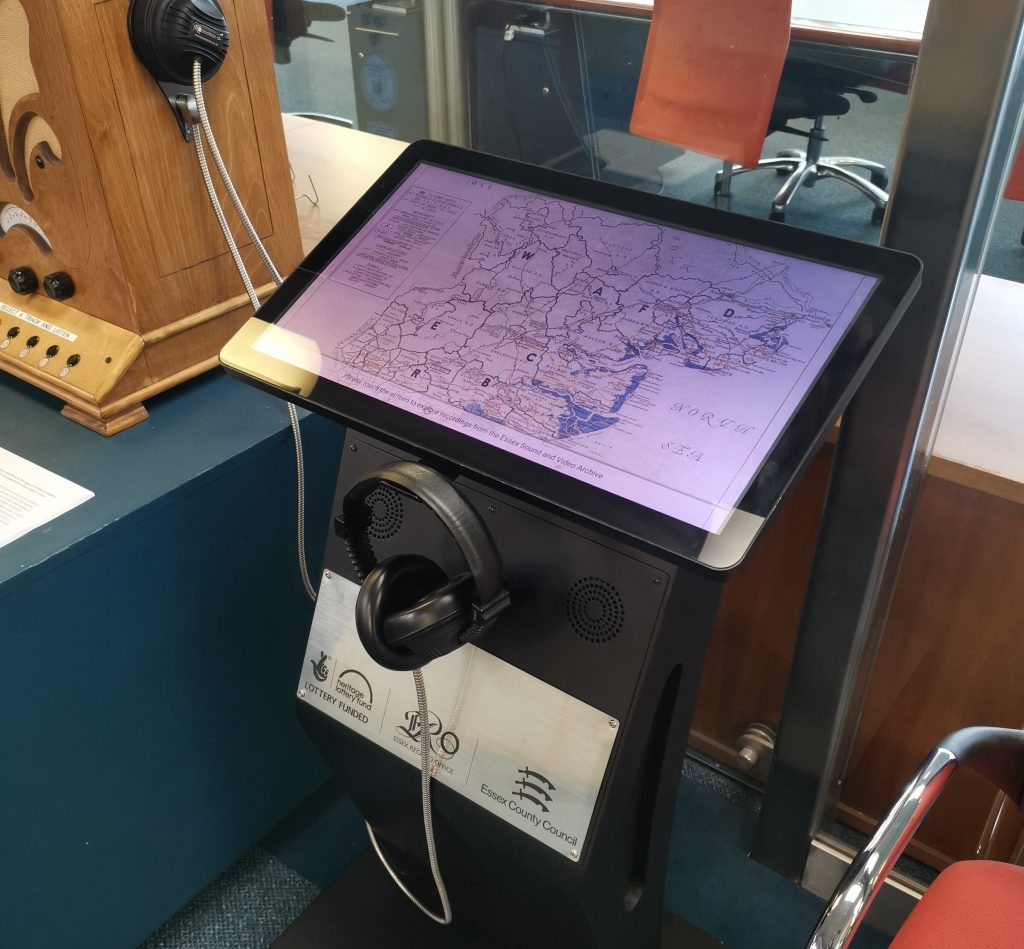

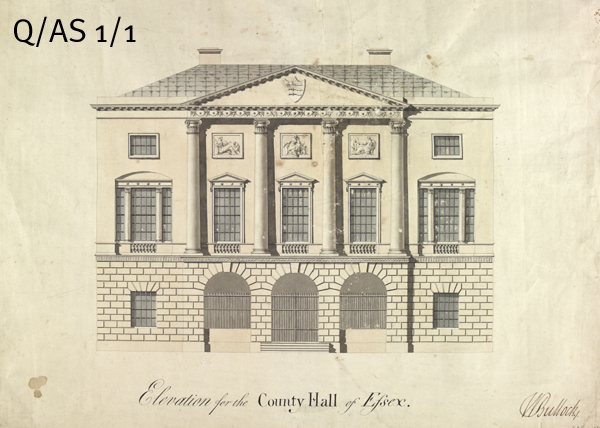

You can listen to all of these clips – and more – at the listening post in our Searchroom. We’ll also be at Canvey Library on Wednesday 1st and Thursday 2nd February, and at Harwich Museum on Saturday 4th February. Find more information here.

You can access many of the full recordings in the Playback Room at the Essex Record Office. To explore the archives we hold relating to the 1953, see our source guide.

The story of the floods on Canvey Island was told in a film made by Essex County Council’s Educational Film Unit that same year, ‘Essex Floods’ (VA 3/8/4/1). You might recognise some of the audio from the documentary ‘Learning From The Great Tide’, broadcast on BBC Radio 4 earlier this week. The new interviews recorded for the documentary will be preserved in the ESVA for future generations.