“So far as destroying the world was concerned, well, you might just as well try to disturb a charging hippopotamus by throwing a baked bean at it.”

Patrick Moore on Halley’s Comet, Colchester Hospital Radio, 1986

Until the end of the nineteenth century, most astronomical research in Britain was funded and carried out by private individuals of independent means. There were several such individuals based in Essex, including Revd. James Pound, his nephew Revd. James Bradley, and Joseph Gurney Barclay.

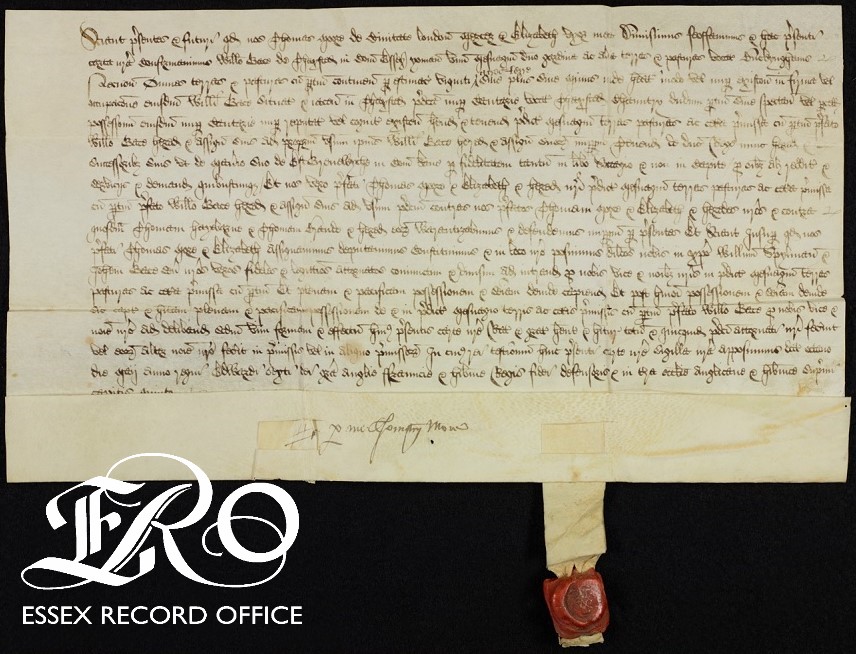

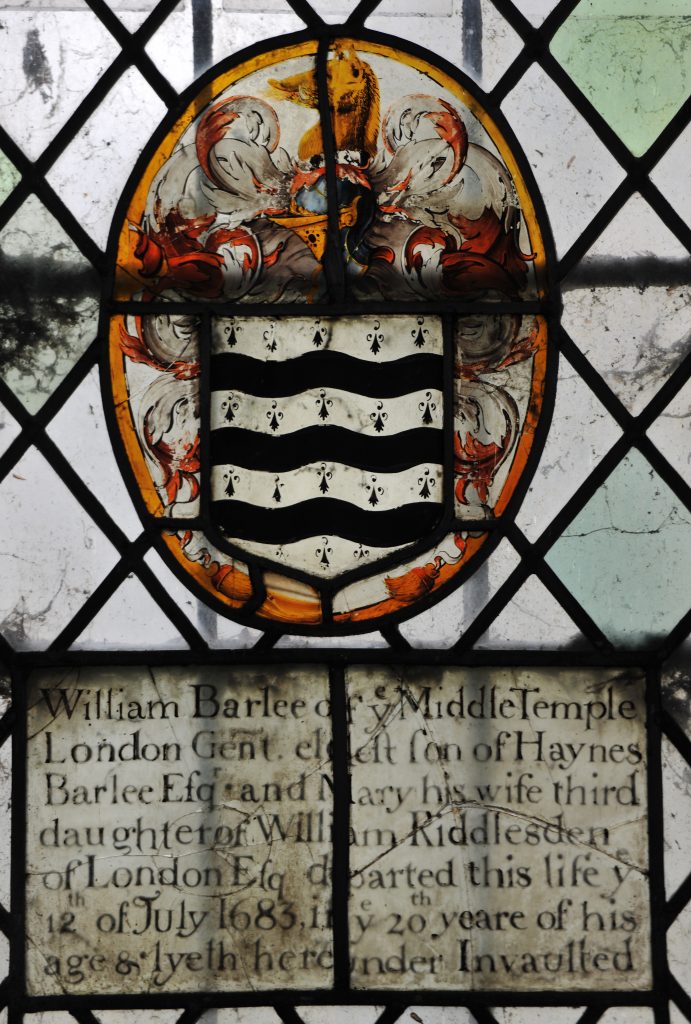

The Revd. James Pound (1669-1724) was Rector of Wanstead, then in Essex, between 1707 and 1720. During this time he made various planetary observations, at first with a 15-foot telescope and then with a 123-foot ‘object glass’ telescope, which the Royal Society lent to him in 1717. The telescope was constructed by Christian Huygens and mounted in Wanstead Park on a maypole that had just been removed from the Strand and presented to Pound by Sir Isaac Newton. Pound’s observations of Jupiter, Saturn, and their satellites were used by several eminent scientists, including Edmond Halley – more on him later.

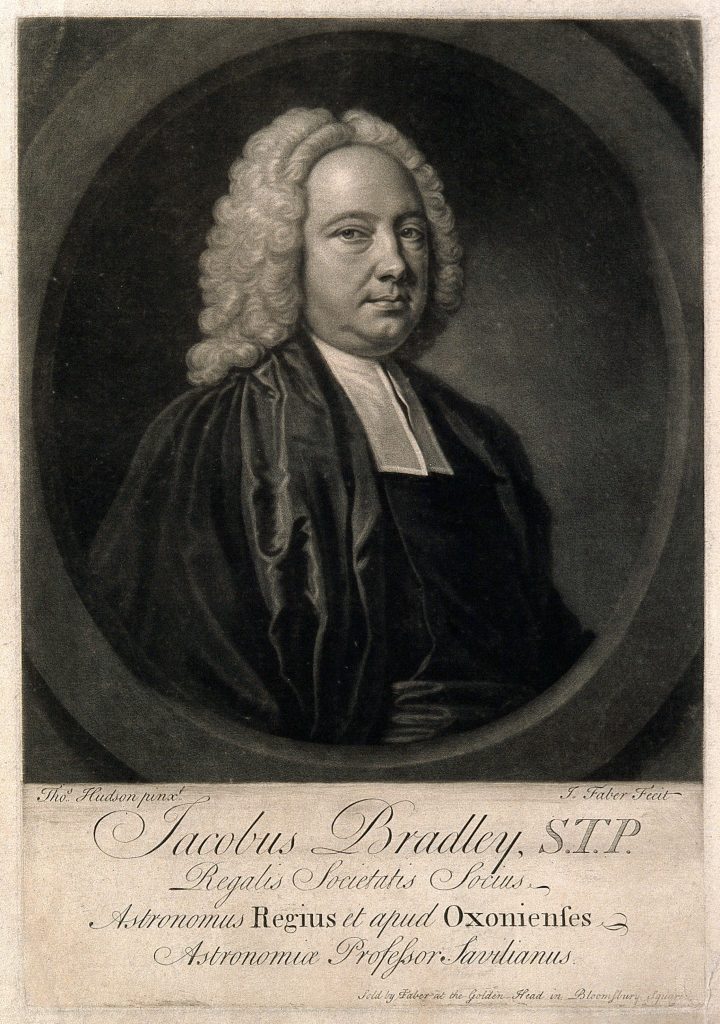

Reference: Wellcome collection 1341i

Revd. Pound tutored his nephew, James Bradley (1693-1762), in astronomy, with many of Bradley’s early observations made jointly with his uncle at Wanstead. In 1718 Bradley followed Pound in becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society, and after Pound’s death in 1724 he continued to make observations from Wanstead at the Grove, the house to which his aunt had moved in her widowhood. Here he installed an instrument even the Observatory at Greenwich didn’t possess: a zenith sector of 12 ½ radius and 12 ½ º. When he left Wanstead in 1732 he left the zenith sector in place, frequently returning to carry out his research, which led to him succeeding Halley as Astronomer Royal in 1742. His research culminated in the discovery of two major phenomena: the aberration of light and nutation (wobbling) of the Earth’s axis. In 1749 Bradley moved the zenith sector to Greenwich, where it can still be seen today.

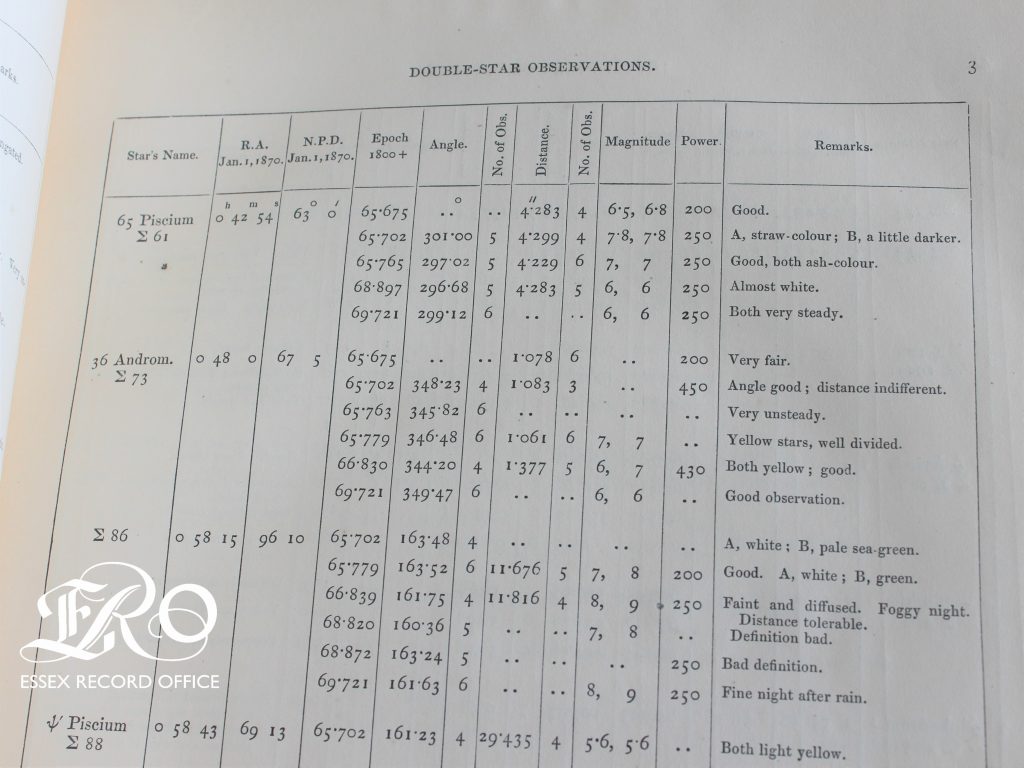

In the autumn of 1854, over a century after James Pound and James Bradley were conducting their research in Wanstead, Joseph Gurney Barclay (1816-1898) set up an observatory at his home in Knotts Green, Leyton. The ERO Library has two volumes of his Astronomical Observations published in 1865 and 1870. These include details about the observatory and its equipment as well as the observations of double-stars, planets and comets. He writes:

My Observatory is erected in the midst of the pleasure-grounds which surround my residence at Leyton, in Essex, about six miles N.E. from the City of London; its position being 51o 34’ 34” N. latitude and oh om oS.87 W. longitude, and about ninety feet above the level of the sea. The building consists of a quadrangular room, sixteen feet square, surmounted by a wooden dome, covered with copper and lined with American cloth, which I found prevented the internal condensation of vapour; it revolves on gun-metal wheels connected by a ring (in mechanical phraseology a “live-ring”).

Barclay employed the services of professional astronomers: first Herman Romberg, who left in 1864 to take up a position in the Berlin Observatory; then Charles Talmage, who wrote up Romberg’s observations for the English press and continued the work of recording “Planetary and Cometic Observations” from Knotts Green. Although comets were recorded from this observatory, none were Halley’s Comet.

Amongst the astronomical phenomena recorded from Barclay’s Leyton observatory were comets. Prior to Edmond Halley’s work, comets were widely thought to be unique objects that passed through the solar system once and then disappeared forever. Using Isaac Newton’s laws of gravitation and planetary motion, Halley calculated the orbits of several comets. He noticed that the orbits of three particularly bright comets observed in 1531, 1607, and 1682 were strikingly similar, and proposed that these three comets were, in fact, the same object making periodic returns to the inner solar system. Based on his calculations, Halley predicted that this comet would return in 1758. The comet did return as he had anticipated, but Halley died in 1742 so did not see his prediction proved accurate. To honour Halley’s ground-breaking work, this comet was later named Halley’s Comet.

Astronomers have now linked Halley’s comet to observations dating back more than 2,000 years. One such observation is its appearance in the Bayeux Tapestry which depicts the events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066.

As seen by the recordings of Halley’s Comet over the centuries, comets and other celestial events really capture people’s attention. Several of the diaries and personal papers looked after at the ERO have references to Halley’s Comet in 1910. In her memories of her youth in Great Waltham, Mildred Joslin recalls seeing Halley’s Comet with her family (catalogue ref: T/P 306/1 page 9):

I remember seeing Hayley’s [sic] Comet, we stood in the road at the bottom of South St, looking towards the school; it came from the right, where Cherry Garden Estate is now, but in those days it was a field. I also well remember standing in the road with my parents and several other people looking at what seemed to be flames in the sky; someone said they were the Northern Lights.

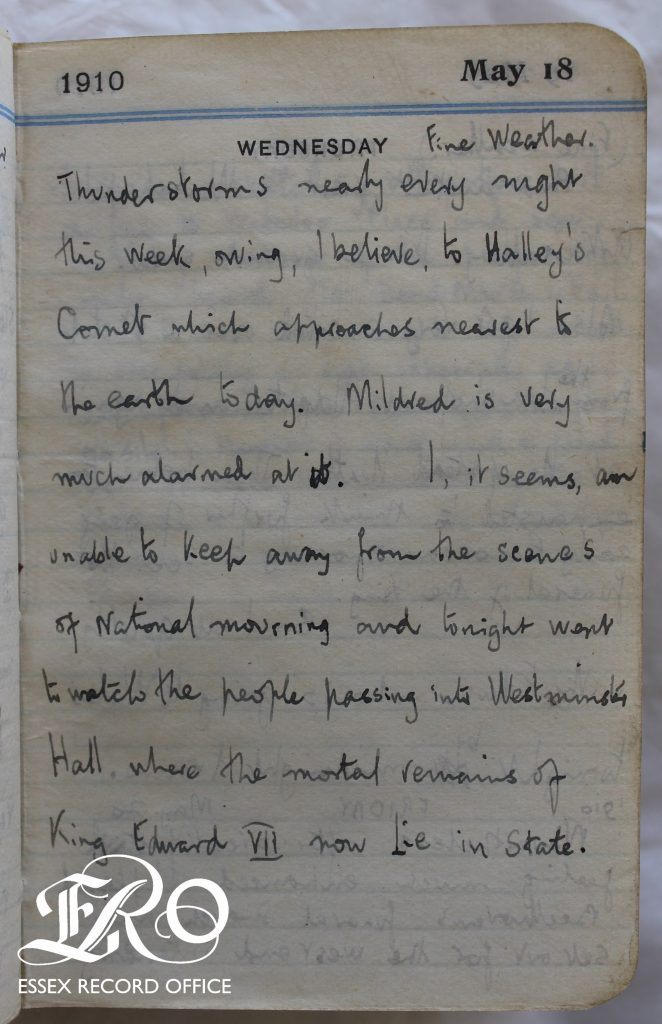

George H. Rose (1882-1956), a talented artist, working chiefly in water colours, kept diaries which present a vivid picture his youth spent his live sketching, going to art exhibitions and concerts, piano-playing, singing in his lodgings – and seeing Halley’s Comet. His entry for 18 May 1910 reads:

Fine weather.

Thunderstorms nearly every night this week, owing, I believe, to Halley’s Comet which approaches nearest to the earth today. Mildred is very much alarmed at it. I, it seems, an unable to keep away from the scenes of National mourning and tonight went to watch the people passing into Westminster Hall, where the mortal remains of King Edward VII now lie in State.

Rose mentions that his companion, Mildred, was “very much alarmed” by the comet. There had been much anticipation for the comet’s arrival in the press and the belief that it was an omen did cause fear in some people, intensified by the death of King Edward VII just days before the comet arrived. It also came especially close to Earth on this occasion: so close that on 19 May 1910, Earth passed through its tail. This was the first time that the Halley’s Comet was photographed and that spectroscopic analysis could be carried out. It was also discovered that the toxic gas cyanogen was present in the tail. This led the astronomer Camille Flammarion to claim that, when Earth passed through it, this gas would lead to an end of life on Earth..

Rose, however, didn’t seem particularly impressed by the comet, writing on 23 May 1910:

The weather was grand all day, and after a visit to Robersons for some more sepia and some REED PENS I drifted to the Heath and there at last learned how to use these pens.

Later after moonrise I stood among the crowd on the other side looking at the comet. There was a large crowd for such a little sight.

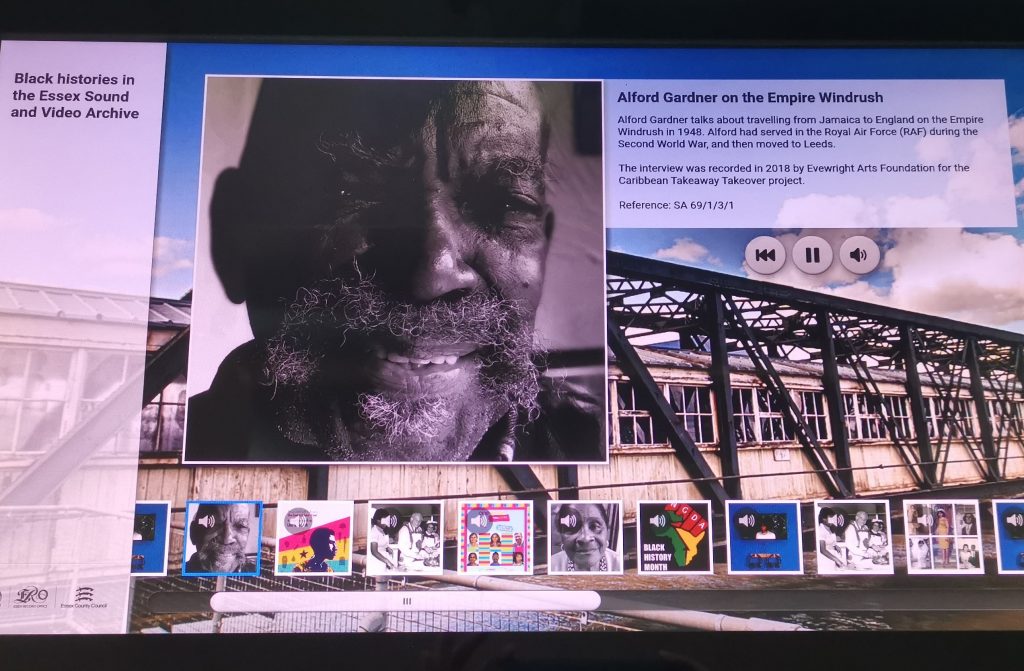

I remember studying Halley’s Comet at primary school when it returned in 1986. It was a very exciting topic, even though the view of the comet on this occasion wasn’t as good as in 1910. In the Colchester Hospital Radio archive – one of several hospital radio archives preserved in the Essex Sound and Video Archive – is an interview with the well-known astronomy writer, researcher, radio commentator and television presenter Patrick Moore (1923-2012). In the recording, Moore reassures listeners that a comet striking Earth would cause local damage but “so far as destroying the world was concerned, well, you might just as well try to disturb a charging hippopotamus by throwing a baked bean at it”.

Nowadays, astronomers can now see Halley’s Comet at any point in its orbit, but the next time it will be visible from Earth with the naked eye will be in 2061.