Shire Hall is one of Chelmsford’s most significant landmarks, and features heavily in our collections of images of the historic city centre. From its opening in 1791 until 2012, Shire Hall served as the County Court. As the County Council asks residents to submit ideas for the building’s future, we took a look back through the archives to see what they reveal about the Hall’s past.

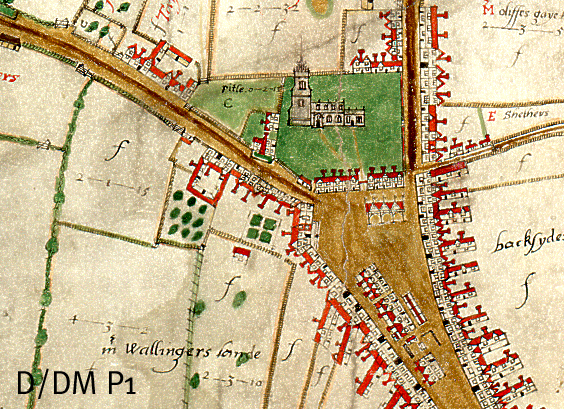

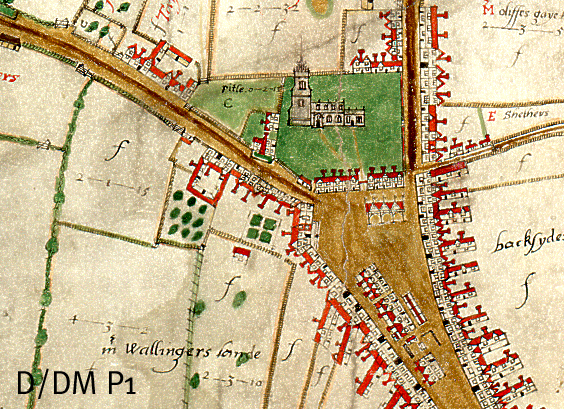

Shire Hall replaced two earlier buildings which served as the county’s court rooms. The Tudor Market Cross, or Great Cross, had been built in 1569, replacing an earlier Medieval building, and it served as both market place and court house. The ground floor was open-sided, with enclosed galleries above, as depicted in John Walker’s map below. Despite the fact that it was open to the street and dusty, draughty, and noisy, the county Assizes and Quarter Sessions courts were conducted in the open piazza on the ground floor, and corn merchants conducted their trade there on Friday market days.

At some point between 1569 and 1660 a second, smaller court building was built, apparently on the west side of the Great Cross, known as the Little Cross. While the Great Cross continued to host the Crown Court, the Little Cross hosted the Nisi Prius (civil) Court.

Extract from John Walker’s 1591 map ofChelmsford, showing the north end of the High Street, with the Tudor Market Cross building in the centre of the market place (D/DM P1)

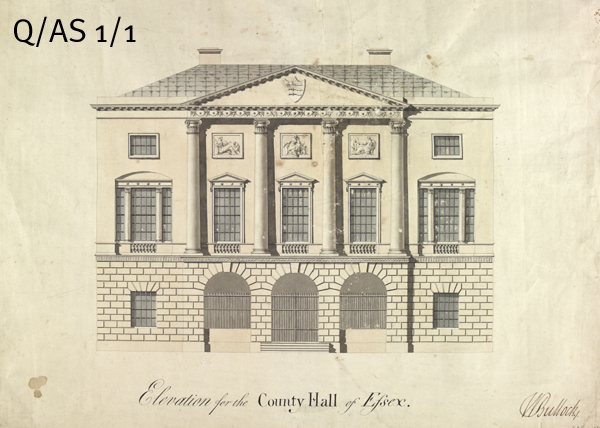

In October 1788, the Tudor court houses were condemned by the Quarter Sessions as ‘not in a fit condition for transacting the publick [sic] business of the County’, and the County Surveyor John Johnson was commissioned to build a new ‘Shire House’.

The authorities quickly settled on a site for the new building at the north end of the High Street, between the market place and the churchyard, which was then occupied by the existing court houses and several private properties. The new building was to be set further back from the market place, offering some relief to the traffic bottleneck at the top of the High Street.

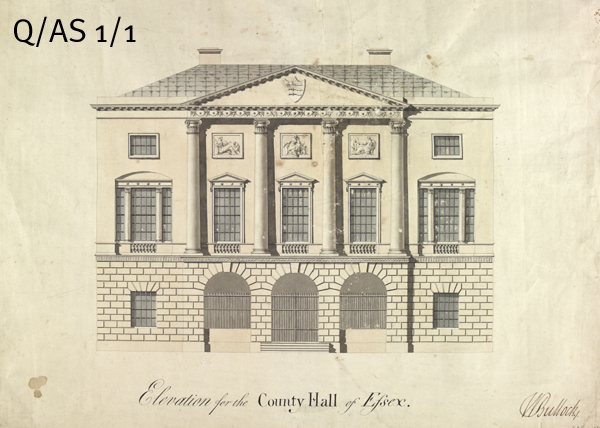

We are fortunate to have John Johnson’s original plans for the building, including elevations of the south, west and north sides of the buildings, and plans of each of the four storeys, with the plan for the ground floor including internal layouts for the Nisi Prius and Crown Courts. In 1789, a county rate was levied to raise £14,000 to buy the site and construct the new building.

Plans and elevations for the ‘County Hall of Essex’, 1788 (Q/AS 1/1)

The builders of Shire Hall encountered some of the problems experienced today when working on enclosed sites in built-up areas; the old courts were not demolished straight away as they had to carry on functioning, and the churchyard could not be turned into a builder’s yard, so a field was leased in Duke Street to assemble and store materials and carry out preparative carpentry and masonry work. Contractors complained bitterly about the extra time, effort and monetary cost of transferring materials, and also the interruptions to their work caused by the running of the court, and by the annual fairs in May and November.

Despite these challenges, the new building was completed in 1791, and the old courts demolished, revealing the impressive Portland Stone façade of the new Shire Hall.

Shire Hall soon after its opening. Engraving by J. Walker after an original picture by Reinagle, 1795 (I/Mb 74/1/59)

The three central arches of the new building led into a large hall, which replaced the old Market Cross and functioned as market space and corn exchange. Beyond the market hall at the back of the ground floor Nisi Prius and Crown Courts, and a retiring room for judges. A grand staircase lit by a glazed dome led out of the market hall up to the grand jury room and the ‘county room’ or ballroom, which took up the whole of the front of the first floor. There was also a small waiting room for witnesses and an office for the Clerk of the Peace and his records. The building’s façade included three emblematic figures by John Bacon, representing mercy, wisdom and justice.

On 3 June 1791 the Chelmsford Chronicle gave its verdict the transformation to the town centre. The new building ‘…exhibits a splendid object to all persons coming up the town; this elegant building when completely finished will not only do credit to the taste and spirit of the magistrates of this opulent county, and honour to the architect, but will be of the greatest service and accommodation to every person frequenting the public meetings.’

Hundreds of thousands of cases have since been heard in the court rooms of Shire Hall since that time, including witchcraft trials in which women were sentenced to be burned alive, and trials which sentenced people to transportation for what would now be considered minor offences.

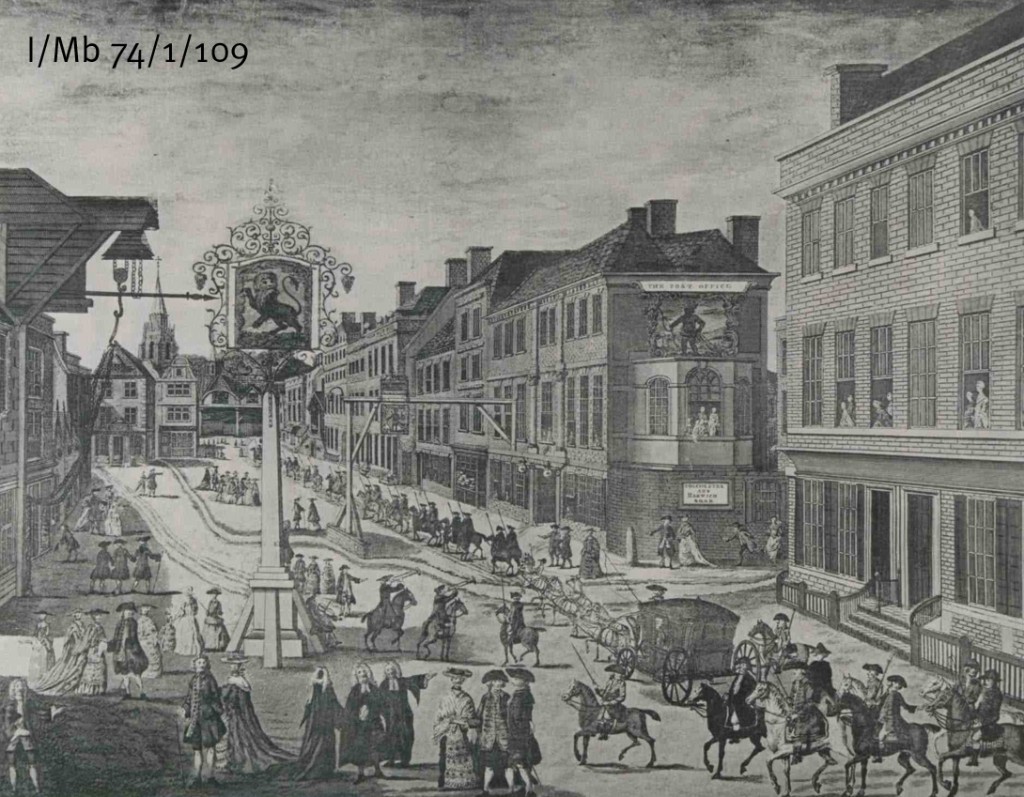

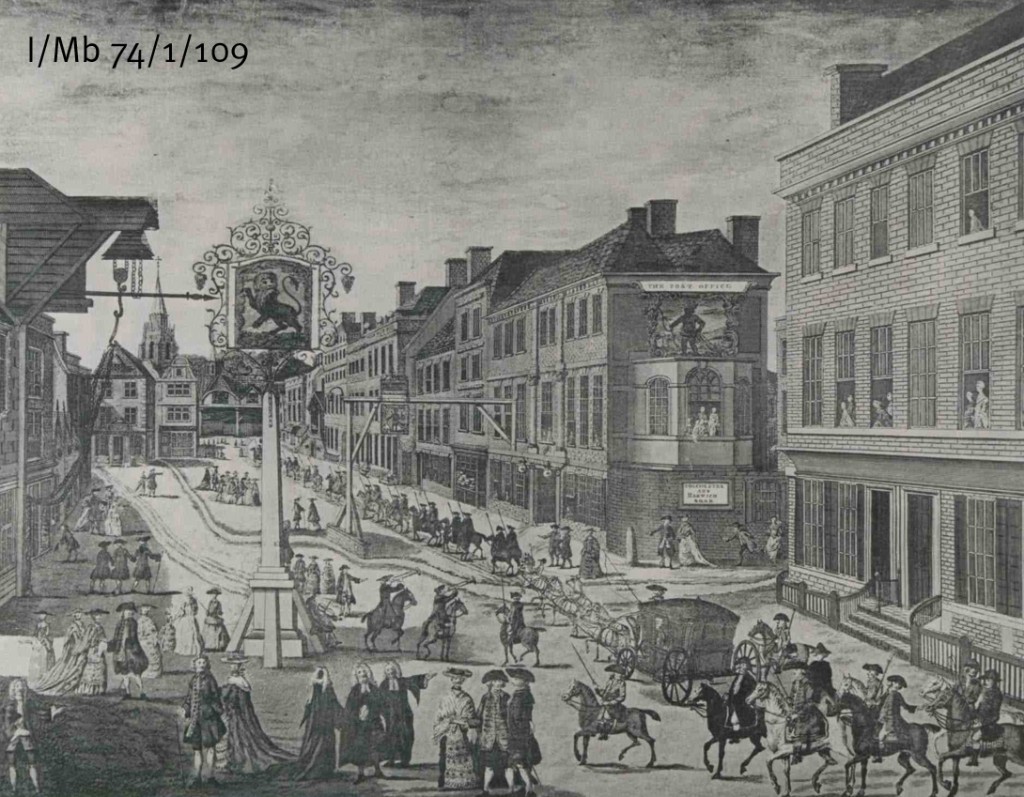

Shire Hall has also been the focal point of many grand occasions inChelmsford. Not least of these were the judges’ processions which opened the Assizes each year (where the most serious cases were heard). This was a tradition that continued until the late nineteenth century; prolific photographer and Mayor of Chelmsford Fred Spalding, reminisced in the 1930s:

‘Even the coming of the Judge to open the Assize has altered. It was a great event in my young days – the High Sheriff with his carriage and four horses, trumpeters, marshals, footmen with powdered wigs. I can remember the late Mr. John Joliffe Tufnell ofLangleys, Gt Waltham was Sheriff. A procession of tradesmen, farmers and others from the town and surrounding villages of nearly a mile long, went out to Broomfield to meet him and accompany him to Church with the Judge.’ (D/Z 206/1/93)

Engraving by J. Ryland showing the judges’ procession through Chelmsford High Street before the opening of the Assizes, attended by the High Sheriff and his officers. Pre-1788 (I/Mb 74/1/109)

Shire Hall has also been the iconic backdrop to the many large gatherings of Chelmsford residents in Tindal Square which have accompanied momentous occasions such as pronouncements of new monarchs and election campaigns, as well as social gatherings.

George V is proclaimed King from the steps of Shire Hall by the High Sheriff of Essex, Ralph Bury, 1910. Photograph by Fred Spalding (SCN 1445)

Election of 29 October 1924, candidates addressing the public in front of Shire Hall. Photograph by Fred Spalding (SCN 3396)

Dance in the ballroom, c. 1924. Photograph by Fred Spalding (SCN 4476)

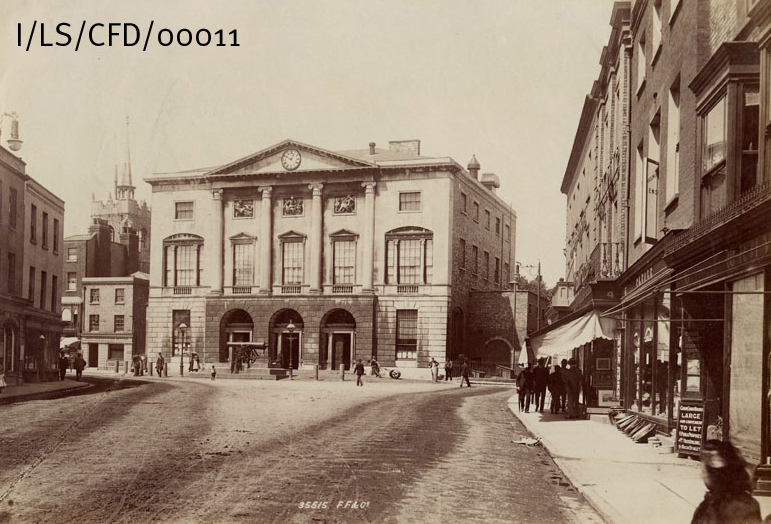

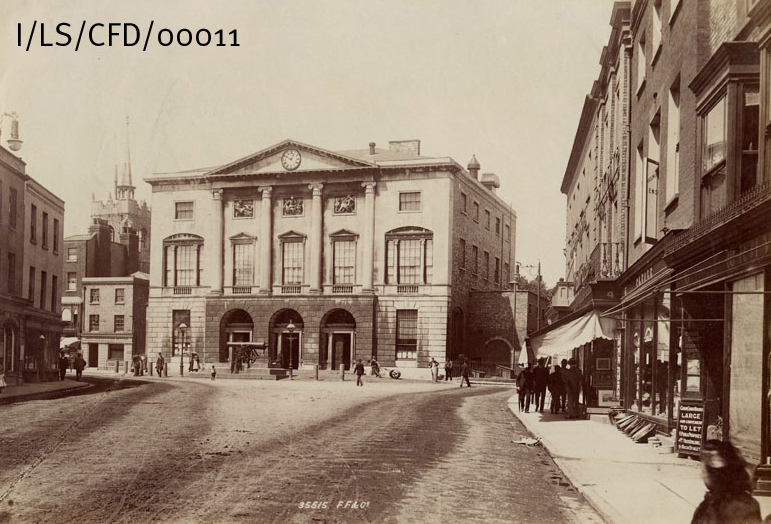

The exterior of the building is little changed today; the west side was extended in 1851, and the east side remodelled in 1903-06.

Shire Hall in 1895, with addition on the west side, and the clock added to the pediment (I/LS/CFD/00011)

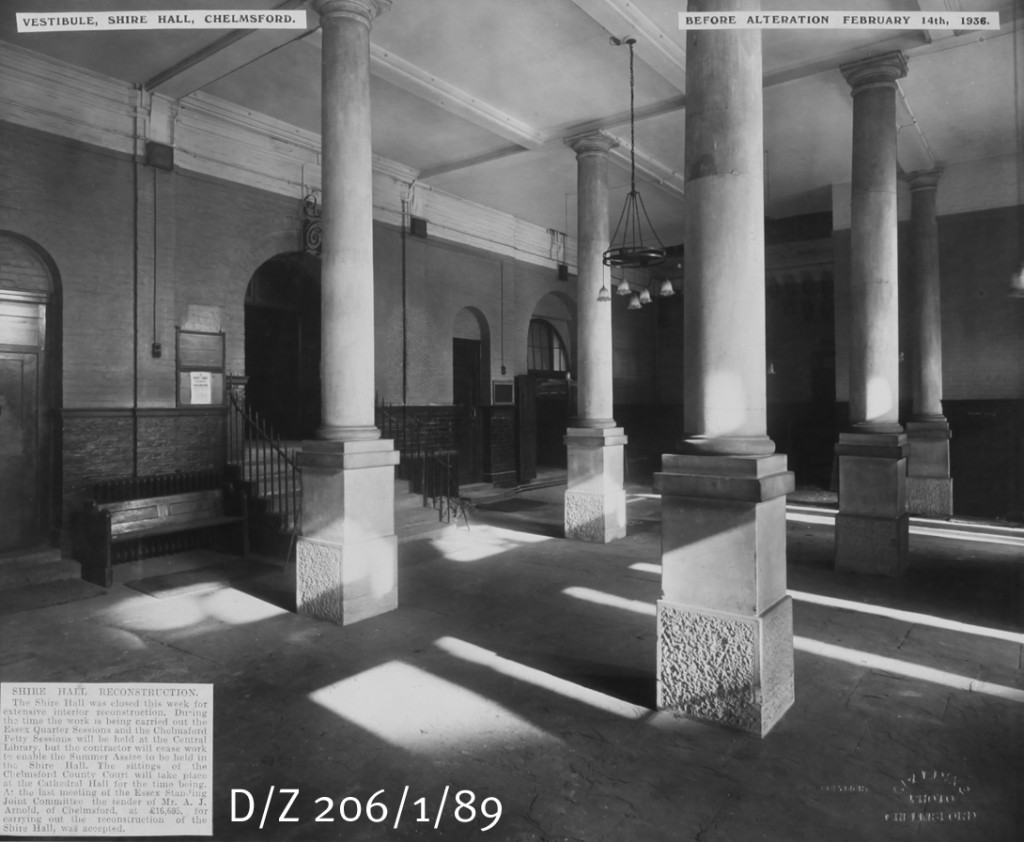

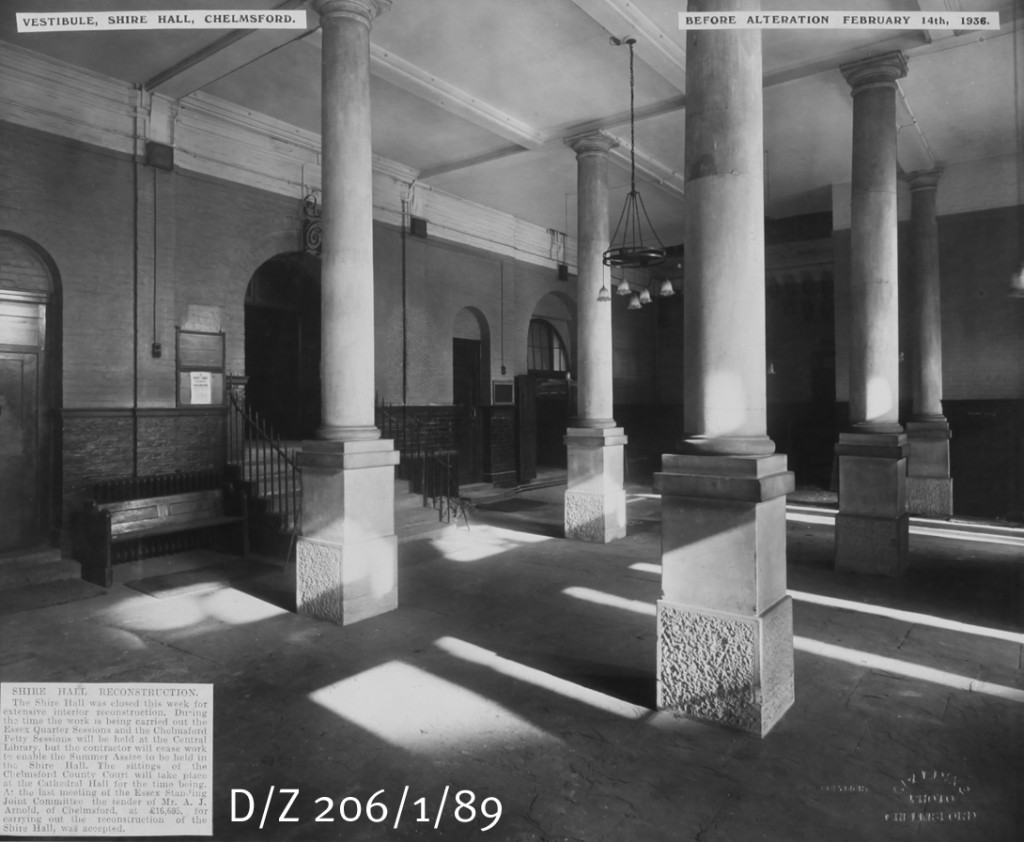

The interior, however, underwent more radical changes in 1935-6, when the lobby, courts, picture room and stairwell were substantially reconstructed by the County Architect J. Stuart, bringing in Art Deco aspects. These features are today considered to be an essential part of the building’s architectural character, but they were not universally accepted at the time. Fred Spalding, who took a particular interest in Shire Hall, was dismayed by the changes:

‘…alas!, what of the interior? During 1936, the architects of the present day, have altered it to such an extent that those who knew it, now fail to recognise it. The vestibule has had all its stately columns removed and now looks more like the entrance of a modern cinema. The Crown Court and Nisi Prius Court have been strip[p]ed of all their old solemnity…The whole atmosphere is changed.’ (D/Z 206/1/93)

Photograph of the Crown Court room in Shire Hall, taken by Fred Spalding before the alterations in 1936 (D/Z 206/1/89)

Court room after the 1930s alterations (SCN 4191)

The vestibule before 1936 alterations. Photograph by Fred Spalding (D/Z 206/1/89)

The vestibule after the 1930s alterations (SCN 4211)

Shire Hall is an important focal point in Chelmsford’s history, and in the present cityscape. Listed at Grade II*, it is recognised as a building of great significance.

If you would like to find out more about this Chelmsfordian icon, you can search for Shire Hall on Seax, or see Hilda Grieve’s magnificent history of Chelmsford The Sleepers and the Shadows, available in the ERO Searchroom and libraries across the county. To find out more about Shire Hall’s architect, see John Johnson, 1732-1814: Georgian Architect and County Surveyor of Essex, by Nancy Briggs, again available in libraries around the county and the ERO Searchroom (in the ERO library and also for sale).

To take part in the future use of Shire Hall consultation visit www.theshirehall.com or email shire.hallconsultation@essex.gov.uk.

The closing date for comments and expressions of interest is Friday 15 February 2013.