Ahead of The Fighting Essex Soldier: War Recruitment and Remembrance in the Fourteenth Century on 8 March 2014, we take a sneak preview at another of our speaker’s subjects – Gloria Harris’s research on medieval Essex knight Sir Hugh de Badewe.

Sir Hugh de Badewe (c.1315 – c.1380), of Great Baddow near Chelmsford, was a prominent Essex knight of the mid-fourteenth century. He took part in military expeditions to the Low Countries at the beginning of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) in the retinue of William de Bohun, 1st Earl of Northampton, and may have fought at the naval Battle of Sluys in 1340. In a military capacity he is next heard of on August 8th 1347 at Calais. It was here that he was rewarded by Edward III with an exemption for life from serving on assizes, juries and from appointments as mayor or sheriff for ‘good service in parts on this side of the sea’. The Siege of Calais, following on from the English victory at Crecy, had lasted for nearly a year and took a major effort on the part of the English Crown to succeed. Possibly Sir Hugh was being rewarded for having taken either crucial supplies or reinforcements of troops from Essex over to France; perhaps he even fought in the siege lines himself.

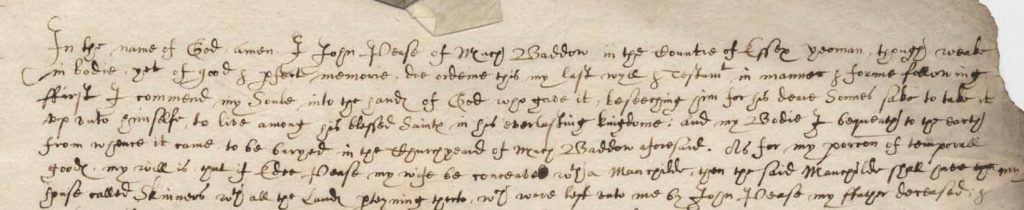

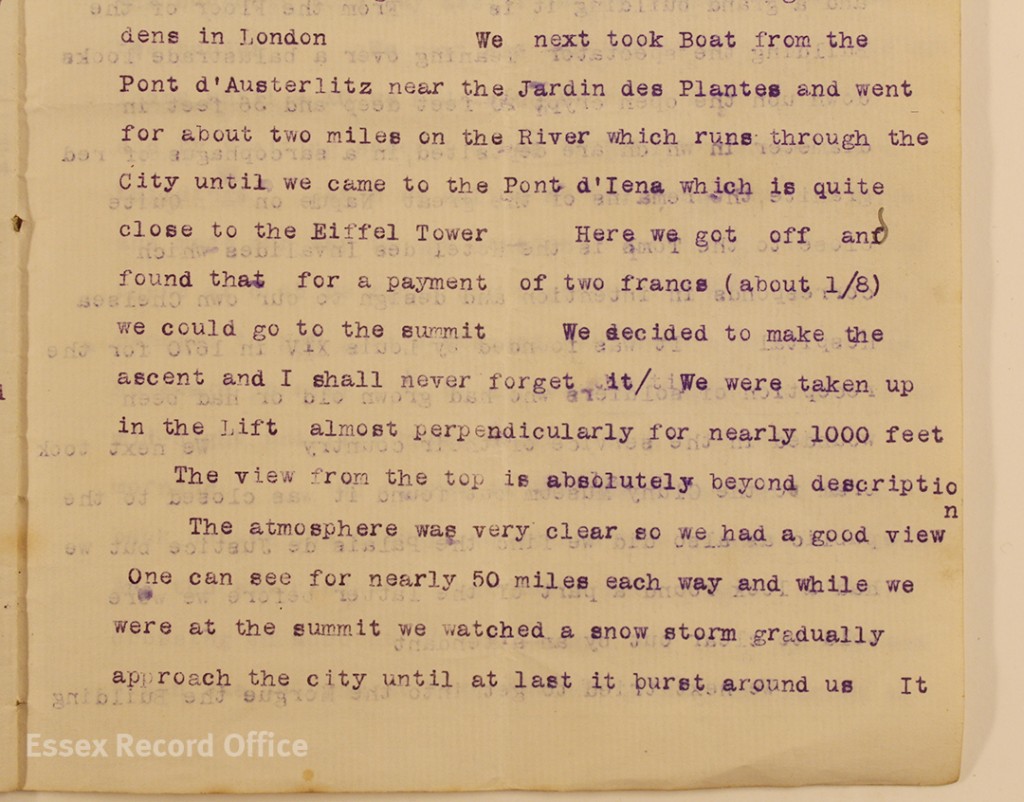

The Battle of Crecy, from a 15th-century illuminated manuscript of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles

So, a near contemporary of the successful Edward III and a participant in the chivalric deeds of the times, living up to our modern-day image of the medieval knight. However, Sir Hugh was certainly not ‘a verray, parfit, gentil knight’, but, as with many other knights of the time, he was also involved in a certain amount of law breaking, or to be more precise, gang warfare. Gang warfare, in which Sir Hugh seems to have participated wholeheartedly, took place in the wider, later-medieval context of criminal activity generally and of criminal bands in particular. Lawlessness on this scale was not new and it was not confined to Essex. Organised crime was perhaps the biggest danger to public order during the later medieval period. Criminal bands could number from two or three members to two or three hundred, depending on the type of offence. In many cases the criminals themselves were often assisted by local men and women, called receivers, who were not involved directly in the attacks but helped the gangs in other ways such as providing food and shelter or perhaps valuable information based on local knowledge.

Mostly criminal gangs were drawn from members of the gentry, men like Hugh who were knights, and esquires. Although the gentry were certainly most prominent in the criminal bands, other members might be engaged in a variety of occupations. Of the three attacks in which Hugh is known to have taken part, it is the first in 1340 that is, arguably, the most interesting in terms of the numbers involved and in the social composition of the criminal band. Upwards of thirty four men were involved when they mounted the attack on John de Segrave’s property in Great Chesterford. Heading the list of offenders was the magnate John, earl of Oxford. Second on the list was John Fitz Walter, a young Essex land owner who was to gain much notoriety as an Essex criminal in future years and third was Bartholomew Berghersh, whose father was Lord Chamberlain to Edward III.

While some gangs may well have had their origins in the halls of the nobility, the links between Hugh and the gang members involved the 1340 attack appear to have had more to do with their military connections than adherence to a particular magnate household, although it is often difficult to make a distinction. While Hugh’s maiden expedition to France, at the very beginning of the Hundred Years War in 1337, may well have been his first introduction to particular noblemen and knights of the military community, some of these men were already acquainted with each other following their shared experience of active service in the war against Scotland.

Sir Hugh de Badewe is not an extraordinary case, but is all the more interesting for it, since his story is a typical one of the time. To find out more about the life and crimes Sir Hugh de Badewe, join us for Gloria’s talk at The Fighting Essex Soldier on Saturday 8 March.

The Fighting Essex Soldier: War Recruitment and Remembrance in the Fourteenth Century

Saturday 8 March 2014, 9.30am-4.15pm

More details here

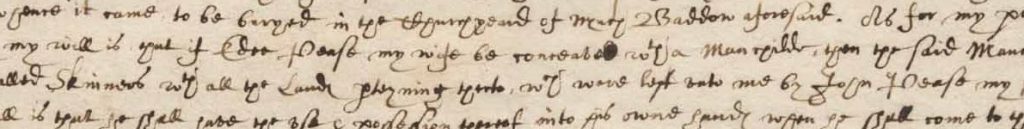

One of our speakers, Dr Jennifer Ward, has also curated a display of fourteenth-century documents from our collections to accompany the conference which will be in the Searchroom from January-March.